Midday in Jerusalem

Weird Serial Fiction With Middle Eastern

Settings

The Agony Column for Monday, April 22,

2002

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

|

|

Edward Whittemore lived in Jerusalem while he wrote

the Jerusalem Quartet. Alas, this incredible bit of writing

never quite caught the attention of the literary readers or

the readers of fantastic fiction, though it was sort of

marketed to both. This summer, Old Earth Publishing hopes to

resurrect the five novels he wrote.

|

Books about the Middle East are flying off the shelf so fast

booksellers practically need a gattling gun to eject them. Most of

these are reprehensible instant books of varying pedigree, catering

to the fear Americans feel since the destruction of the World Trade

Towers over seven months ago. I can't say whether any of them are

worth the reader's time. I don't intend to buy or read any of them.

While I understand that people are curious about aspects of a culture

they used to ignore but now find shoved in their faces, I don't

particularly share their curiosity, and I don't think that

Johnny-come-lately learning serves to do anything other than confirm

existing fears and prejudices.

After all this whinging about crass commercialism and mass

mentality, I can parade my utter hypocrisy by admitting that I'm

currently reading a fascinating series of books about -- the Middle

East. Most of my Middle Eastern reading has been in the field of

weird literature. There's been a fair amount of great Middle

Eastern-oriented weird books published. I'll start with (what I think

are) the basics, and end up with the Arabesks, a wonderful new set of

novels from Jon Courtenay Grimwood.

|

|

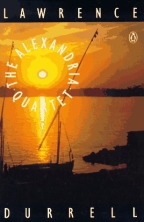

Lawrence Durrell's Alexandria Quartet set the standard

for a fictional series set in the middle east. He made the

setting a character and performed grand literary

experiments, but the Nobel Prize escaped him.

|

The most basic -- and least 'weird' -- sets of books about the

Middle East come from Lawrence Durrell (1912-1990). I've read two

series by this writer, and they both stuck with long afterwards. The

first was 'The Alexandria Quartet', which was once thought certain to

earn Durrell a Nobel Prize for Literature. 'The Alexandria Quartet'

is comprised of the novels 'Justine' (1957), 'Balthazar (1958),

Mountolive (1959) and Clea (1960). He followed this with a duet of

science fiction novels -- 'Tunc' about the invention of a

supercomputer named Abel, the second 'Nunquam', about the creation of

a perfect robotic woman. All of them are probably the sort of novels

best enjoyed while you're in college. But for all their overheated

fervor -- and there's a lot of it -- the mark they make on the reader

and have made in the literary landscape is indelible.

In the Alexandria Quartet, the Middle East becomes a character. A

set of events described by one character is told differently when

recounted by another. Durrell explores sexual ambiguity, extremes of

passion, espionage and addiction with an enthusiasm that is itself

lurid. He torments the normal novelistic form, inverting the

importance of events and subverting the consistency of the

characters. Like a languid hangover afternoon, the novels spend long

stretches staring at their surroundings. When they came out their

were revolutionary, visionary. Now they are more like elder

revolutionaries and one-time seers, still mysterious but crinkled

with the lines of an age gone by. They are still striking, but they

failed to change the world. It's not an uncommon fate, especially

when the movie adaptation flops, as did 'Justine'.

|

|

|

In 'Tunc', Durrell included science fiction themes in

his work. 'Tunc' details the creation of a superncomputer

named Abel, and host of neuroses embodied in characters who

have gone out beyond the edge. I spent five days trying to

find this damn book in my library.

|

Any guesses as to what decade saw the publication of

this book, based on the cover art? 'Nunquam' has the

scientist from 'Tunc' creating an artificial woman. I

managed to find this 31-year old paperback before I could

find that hardcover book.

|

'Tunc' and 'Nunquam' can in retrospect be seen as the first

tenuous explorations into what might later become known as cyberpunk.

They were concerned with technology that mimicked thought that looked

human and was better than human without actually being human. They

were also a tip of the hat to the omnipresence of the corporate

entity. I'll never forget the scheme from 'Nunquam' where a

corporation subsidizes then popularizes the practice of mummification

so that their laboratories, the ones who do perform the process, have

plenty of human bodies to study. 'Never forget' is a phrase you'll

hear associated with Durrell a lot.

|

|

The first novel by Edward Whittemore was actually set

in Shanghai, but many of the characters pop up in his

'Jerusalem Quartet'. It's probably best to read this one

first, though it is certainly not necessary.

|

I found the next treatment of the Middle East in weird fiction at

the original Change of Hobbit bookstore, where Harlan Ellison once

sat to write a short story. I was looking for hardcover copies of

Lovecraft, and saw 'Sinai Tapestry' by Edward Whittemore on the

shelf. A completely inaccurate comparison to 'Lord of the Rings' on

the cover must have drawn me in, and after I bought the book, I spent

the next 16 or so years finding and reading the sequels, only last

year finding the final book in the series. Like the Alexandria

Quartet, Whittemore's series -- the Jerusalem Quartet -- is set

largely (though not always) in the Middle East, featuring a set of

characters who explore the extremes of love, sex and addiction. But

Whittemore has a wider canvas and a different interest than Durrell.

His characters are all looking for the original Bible, which is said

to both confirm and deny the beliefs of all religions.

|

|

The first novel in Whittemore's 'Jerusalem Quartet'

was billed as having some similarities to 'Lord of the

Rings'. Both, in fact, were books. Otherwise...

|

Even the name of the series gives an idea of where Whittemore was

heading. He explores an intricate web of myths within myths, stories

intertwined and characters who include a 1,000-year-old grocer and

the seventh son of a seventh son. When Whittemore wants to hit you,

he uses the same ammo that Durrell used: evocative locations and

memorable details that pin down specific events on a vast Middle

Eastern canvas. But Whittemore has a grander tale in mind, and pulls

it off over the span of the four novels. One of the main characters,

Stern, a gunrunner and sometime opium addict, wants nothing less than

a unified, multi-cultural Palestine. It's no small dream.

|

|

A twelve-year poker game played for the control of

Jerusalem's black market is the centerpiece of this novel.

Any similarities to Tim Powers are strictly coincidental,

but certainly applicable. Fans of Powers who liked 'Declare'

should give these books a try.

|

Whittemore's saving grace is his sense of humor. He infuses all

the books with both clever intellectual jests and bouts of screwball,

physical humor. He brings to mind the best of Vonnegut's jokes,

though he's otherwise little like him. It's a written style, not a

content similarity. Both writers uses a similar linguistic structure

to tickle the reader just often enough, ensuring that no-one waits

too long before hoisting another drink.

|

|

'The Panorama Has Moved'. A character in 'Nile

Shadows' finds a sign with this message in an empty lot

overlooking the harbor. The phrase has always haunted me.

|

'The Jerusalem Quartet' is also gifted by Whittemore's fantastic

imagination. He weaves fearlessly from superstition to supposition to

inspiration as he tours faiths, religions and exotic locales. His

Irish seventh son will end up wearing a fez and playing a poker game

for twelve years to win control of the black market in Jerusalem.

Whittemore can go from a smirk to a scream effortlessly, and the

reader won't know until the smell of burning flesh rises. He works

more the 'magic realism' side of fantasy, never elaborating a strict

set of rules for supernatural elements, instead greeting them as if

they're just part of the everyday lives of some rather eccentric

people. It's a trick used by writers such as Tim Powers, whose

'Declare' is another fine work of Middle Eastern weirdness.

|

|

Edward Whittemore's conclusion to the Jerusalem

Quartet, one of the great lost pieces of undiscovered

literature.

|

Unfortunately, that lopsided 'Lord of the Rings' comparison

probably help sink this series into complete invisibility. In

fairness, the books are probably too 'normal' for a crowd expecting

elves and sorcerers, and too weird for a college professors to teach

in literature classes. They're fairly difficult to find, and will

continue to be so until they're released by Old

Earth books, the people who brought you Patricia Anthony's short

story collection 'Eating Memories' and the recent re-releases of the

E. E. "Doc" Smith novels. According to Michael Walsh of Old Earth,

with luck they should be available this summer. It's fantastic to

hear that these books will be made available again to a new reading

public.

|

|

George Alec Effinger hit a home run with his 1987

effort 'When Gravity Fails'. The title is taken from the

lyrics to Bob Dylan's 'Just Like Tom Thumb Blues'. It's NOT

cyberpunk.

|

My next stop in the Middle East came in the prime year of the

cyberpunk boom, 1987. Veteran SF writer George Alec Effinger

surprised all the young turks and old fans with 'When Gravity Fails'

(1987), followed by 'A Fire in the Sun' (1989) and 'The Exile Kiss'

(1991). Set in an Arabic ghetto called 'the Budayeen', they tell the

story of Marid Audran, who starts as a street hustler and ends up a

policeman. Though due to the timing of their release, these novels

were generally lumped with the cyberpunk crop, they're really not

cyberpunk, and they are not the products of the cyberpunk community.

Effinger was an old hand before most of the cyberpunk authors were

reading, and his sensibility is rather different. If you take the

vibe of the movie version of 'Blade Runner' piped through a Middle

Eastern sensibility filter, then you're getting a much better idea of

what Effinger has to offer in these novels. They're a pitch-perfect

combination of the Phil Dickian science fiction and Chandleresque

noir.

|

|

|

The cover of this novel appears to be heavily

influenced by the movie 'Blade Runner'.

|

Curiously enough, you can get the second and this, the

third novel in Effinger's series, but not the first book. Is

somebody paying attention to this?

|

But more than anything else, they really hit home with their

Middle Eastern bias. Like Durrell and Whittemore, Effinger milks the

Middle East for every bit of dripping, corrupt atmosphere he can get.

He also keeps his hero resolutely downtrodden. There is no

world-saving going on in the Budayeen. There's a lot of drug

addiction, sexual addiction and dirty little secrets enough to keep

the reader glued through three heaping helpings. Curiously enough,

only the latter two novels are in anything remotely resembling

"print". The first is well out of print, when it should be pumped

across bookstore shelves in wonderful, deluxe, illustrated editions.

Fortunately, they're still pretty readily available used, and they

will not require the sale of a limb of organ, even though they may

describe that as status quo.

The latest author to enter the Middle

Eastern strange fiction arena is Jon Courtenay Grimwood. Last year he

started with 'Pashazade:

The First Arabesk', nominated for an Arthur C. Clarke award, and

he's just released the follow-up 'Effendi:

The Second Arabesk'. Drawing from a rich line of predecessors

they meet the standards of their forebears. They acknowledge their

heritage as well: both books mention Durrell's works on the jacket

flaps, and like the works that came before them, they acknowledge

that the place is a character in itself. The Middle East has hooked

Grimwood and not let him go.

|

|

Jon Courtenay Grimwood's 'Pashazade' has a fantastic

trailer created for the web. It will make you want to read

the book and see the movie. Alas, the book has not yet (to

my knowledge) been optioned. It should be!

|

But it's not exactly the Middle East we know. The Arabesks are set

in an alternate history, where Germany won the First World War, and

the Ottoman Empire still rules the Middle East. In 'Pashazade',

ZeeZee, a genetically and software enhanced kid from Seattle leaves

town in a cloud of bad blood, on the run from a one-time benefactor

who is now intent on his death. He is brought to El Iskandryia by an

aunt he never knew he had, and set up as one half of an arranged

marriage. Grimwood plunges the reader into this tale of identity,

growing up and the temptations of power with gusto and just enough

mystery to make the world he paints seem larger than the characters

who experience it. That's a tricky line to tread, but Grimwood does

it to perfection.

Never less than compelling, 'Pashazade' and 'Effendi' combine so

many genres so seamlessly that readers' heads will spin if they ever

let themselves have a chance to think about it. But such is the craft

with which the books are written that most readers will never even

get the chance. Like Durrell, Grimwood has perfected the place as

character move, and he uses it to fill the readers' perceptions to

the edges and beyond. He writes a heck of a noir mystery, and his

alternate future is a gritty, entertaining mix of past, present and

future jumbled together in the streets of an ancient city. The

antiquity can never be subsumed by the present or future. Bits of

technology float like shiny plastic wrappers in a harbor crowded with

fishing boats.

|

|

Jon Courtenay Grimwood's 'Effendi' makes the most of

the world and especially the characters he created in

'Pashazade'.

|

However, all of this would be for naught if the readers didn't

like the characters. Here's where Grimwood departs from all his

predecessors in a way that's really clever and really works. His main

character, ZeeZee/Ashraf Bey would be right at home in any novel,

from Justine to 'Sinai Tapestry' to 'A Fire in the Sun'. He's moody,

alert and lives on the edges of reality, as likely to snort a packet

of crystalmeth as to knock back a cup of mud-thick coffee or a

tumbler of whiskey. However, he's surrounded by characters who are

much more grounded and just plain likable. Grimwood develops an

enchanting relationship between Ashraf and his nine-year old niece

Hani, the obligatory computer-genius kid. Such is his craft that she

never seems annoying or grating or patched on. Ditto for Ashraf's

intended wife, Zara. She's just a bit more grounded and yes,

endearing than Ashraf. Finding these nice, normal, likable characters

in the middle of Grimwood's hermetic stew is delightful.

Grimwood's done something

worth noting on the web as well. He's created a flash movie trailer

for 'Pashazade' that will make you want to read the book and pray

that it becomes a movie. It's the best trailer I've seen for quite

some time. You can find it at:

http://www.j-cg.co.uk/pasha.htm

I've kindly put this URL on a line by itself because you'll

certainly want to email it to more than one person. It's a knockout

job, and very clever. It doesn't hurt that Grimwood's novels are both

lower priced (£12.99) and nicely designed by the Earthlight

imprint of Simon and Schuster. If books have to compete with movies

for our attention -- and they certainly do -- then there's not reason

they can't avail themselves of the tools used by movies. Grimwood is

to be congratulated on the excellent programming and art direction of

his trailer. And yes, I do want to see the movie!

From Durrell to Grimwood via Whittemore and Effinger, readers can

easily sink themselves in classic Middle Eastern-oriented literature

that's really weird, but really good. Look for the Whittemore novels

when they appear later this year, or better yet, start out now and

track down the paperbacks. You'll definitely be glad you did. Clamor

for the re-release of the Effinger's Marid Audran books. Sweep the

shelves clean of instant karma. In one small corner of the world, in

one small city on the planet, readers can find a wealth weird reading

that will keep them entertained and challenged, educated and

understanding of not just some sterile facts, but learning just a

little bit more about the human heart. The human heart, as it is so

often spoken of, is not real. It doesn't exist, except in books, and

families and lives. Keep reading and living.

Thanks,

Rick Kleffel