|

|

Golden Gryphon is known for their many find short story collections. I was intrigued by 'The Wild Boy', the only novel I've seen them publish recently. |

|

|

|

The Agony Column for June 11, 2002

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

I am forced to admit that I buy books faster than I can read them. This is partly because I am "saving books for a rainy day". That would be a day of fiscal rain, and I'll be goddamned if it ain't already done come and gone. Slowly, I'm almost catching up with myself. Some of this is the result of actual feedback from readers, who had read the books I mentioned being in the queue and thought I might like them. This upped the position of those books in the queue -- it's only natural. Also, the summer is already upon us, and yes, I'll cop to having already gobbled one of the big ol' pieces of American Cheese on offer this summer. More about that in the next column. This column is going to be devoted to a couple of wonderful, kinda pokey books that it would be easy to pass over. Hell, I thought they looked good enough to buy, and bought them, but then let them get bumped out of the queue time and again for that week's Wonder Bread.

For both, I can thank reader Scott Klobas, who suggested that if I pulled them out of my inbox, I would be pleased with the results. He was right. Both novels are off the beaten track, and both novels share the same virtue, a virtue usually seen as antithetical to summer reading. Both Warren Rochelle's 'The Wild Boy' and Michael Cisco's 'The Divinity Student' are slow reads.

I can't say what it is about summer that encourages us to read huge slabs of cheese. Not that I'm opposed to this, but it would seem that in the summer, when we have more time and more inclination to read, readers would want to dip into something a little more challenging, something that requires and rewards careful reading. Often, readers simply will not want to spring for a novel that is a "slow read". I enjoy books that require more than three brain cells, but I recognize that not everybody does, and in my reviews, you will often note that I will mention (warn) quite pointedly that a particular novel is a "slow read". It's there for your safety!

|

|

Golden Gryphon is known for their many find short story collections. I was intrigued by 'The Wild Boy', the only novel I've seen them publish recently. |

'The Wild Boy' not surprisingly, is something of a throwback. Set in the year 2155 after an alien invasion of earth, it's a science fiction novel without cyber-anything. Any gene-splicing is soft-focused into the background. The military campaigns occupy about six single pages interspersed between some of the chapters. Occupying center stage, stage right and stage left are three characters and two complex societies. The novel is about evenly divided between Ilox, a human raised by the Lindauzi, and Caleb, his son, the Wild Boy of the title. The Lindauzi are ursine aliens who came to earth to domesticate humans, to turn them into perfect empathic companions. They wanted to help us --really. Doing so just required an awful lot of killing.

Fortunately, that's mostly offstage in the novel. 'The Wild Boy' treats us to an extended culture clash between the aliens, wild humans, and humans who have been raised by the aliens. Rochelle begins with a careful look at the wild humans (wolves), who live in the ruins of 2oth century earth (the invasion took place on the eve of the millennium). It's an inverted culture -- humans are no longer the dominant species on this planet. The author has a bit of fun with this notion, and the slang developed by the wild humans is slyly informative. But even when the Lindauzi hunt down the wolves, we're not talking about a pulse-pounding piece of action. Instead, there's an atmospheric feel to the action. The main action takes place in the hearts of the characters.

In order for this to happen, the writer has to create some pretty thorough characters, and Rochelle does this with expert ease. His talents are best displayed in the segments set before Caleb's birth, when Ilox was raised as a domesticated human to be part of the grand Lindauzi project to create a domesticated, empathic companion race. Ilox is in fact the most successful human version of that project the Lindauzi are going to come up with; unfortunately, their culture blinds them to this fact. Ilox is the pup given to Phlarx, a young Lindauzi who proves to be not very bright. Every nuance of the relationship, emotional and intellectual, between Phlarx and Ilox is critical to the story. These are the linchpins upon which the story turns, and these small, slow portions of the story are as expertly written. They're the necessary building blocks for the revelations to follow.

The revelatory aspect of this novel replaces the usual action scene that concludes a novel -- or in this case, enhances it. Yes, events do come to a pitch-point, at which cultures will tilt. The main thrust is not in a chase scene, but in the revelation of true motives and the true state of matters both in the heart and in the societies created since the invasion. Rochelle craftily keeps the reader's eyes on the left when something is happening all the time on the right. It's the kind of writing that ups the impact of this novel, and makes it more satisfying that the 500-pound gorilla hulking up the bestseller lists.

|

|

Golden Gryphon is known for their many find short story collections. I was intrigued by 'The Wild Boy', the only novel I've seen them publish recently. |

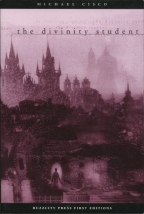

'The Divinity Student' is also a slow read but for very different reasons than 'The Wild Boy'. Rochelle aims for and hits the target of social and emotional connection. 'The Divinity Student' uses language, aims for language, target acquired, target annihilated. It's a word bomb.

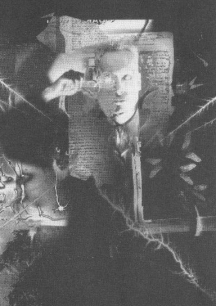

Well, it's quite a bit more than that. Hailing from Buzzcity Press, crediting the ubiquitous Jeff VanderMeer and Ministry of Whimsy Press (publishers of Stepan Chapman's unique 'The Troika'), 'The Divinity Student' is a beautiful book. The cover art is by Harry O. Morris, and he supplies the interior B&W photo(shop) collages that bear his style dating back for many years. The print is large and easy to read. The pages have lots of white space. Flip through the chapters, absorb Morris' odd, disturbing art, then plunge into Cisco's taut linguistic trap. 'The Divinity Student' is going to hypnotize you.

This is in fact Cisco's stated intention and it helps a bit to know it going in. The opening chapter is a dense hallucinatory collage, the written equivalent of Morris' art. It's certainly as ambiguous as the art. It won't help a lot to try to figure out "what's going on" in Cisco's novel. What's going on is that the language is taking to places that language usually does not go. The art has already arrived. Soon, stuffed with words, the reader will arrive in Cisco's San Veneficio. It's a visit you're not likely to forget, though how exactly it will be remembered will vary from reader to reader.

|

|

This barely does justice to the wonderful artwork of Harry O. Morris. His surreal iamges are the perfect match to Cisco's surreal prose. |

If you're tempted to think the novel is too deadly serious, it will take a turn into some screwball imagery. If you're tempted to think that there's no plot, one will present itself. If you're tempted to think that character has been subsumed by the language, then you'll be introduced to someone you'll never forget. It does not matter. Cisco is certain that even if everything is not already subsumed by language, it can be. He does it right before the reader's eyes.

Now reading this type of novel is no easy chore. Plan for a quiet afternoon, away from the radio. You're not going to be able to graze this novel. Cisco's prose isn't exactly poetry, though it has a musical component. It is to poetry as ambient sound collage is to music. There's a beauty here, no doubt about it. There's an intensity of creation that practically whites-out the words. The effect that Cisco attempts and I believe succeeds at creating is to turn the words into a white glare, a point of intensity too bright to regard. But you only find this out after reading -- after you've become that white point of light. The journey there will take you through realms you've not encountered in standard horror or fantasy, though Cisco does have antecedents, in particular Thomas Ligotti. But if Ligotti is opium, then Cisco is heroin. Distilled, it can be deadly, but it can also lead to an intense high. It may also be habit forming.

That Cisco can work his schtick at novel length is certainly an accomplishment. He does provide the basics -- plot, character, place, action. But he delivers them in a small white packet that can just about knock your tiny brain out if you're not carefully prepared. By now readers should have an idea whether or not they'll like Cisco. Some certainly will; others will not. But even if you don't, the novel is well worth the price of purchase. It's beautifully printed and rather cheap. You can afford to buy it and not read it. But if you do read it, prepare yourself.

I'll be off on vacation at the end of this week; the next column will of necessity come on Thursday morning and feature the return of a favored Agony Column Subject, American Cheese. The summer is here, and so are the cheesy puffs. Who can resist just one?

And finally, this just in: Tor has agreeed to publish Neal Asher's very fine, very fun two big slabs of science fiction, 'Gridlocked' and 'The Skinner'. Asher was interviewed for The Agony Column recently. He's hilarious and it's well worth your time to check out his novels and his interview. Congratulations Mr. Asher -- we'll be looking forward to seeing these fine novels soon.

Thanks,

Rick Kleffel