The Agony Column for June 19, 2003

Criticism by Serena Trowbridge

|

|

The UK Adult edition of Philip Pullman's Milton-based trilogy starter. |

|

|

|

The Agony Column for June 19, 2003

Criticism by Serena Trowbridge

|

|

The UK Adult edition of Philip Pullman's Milton-based trilogy starter. |

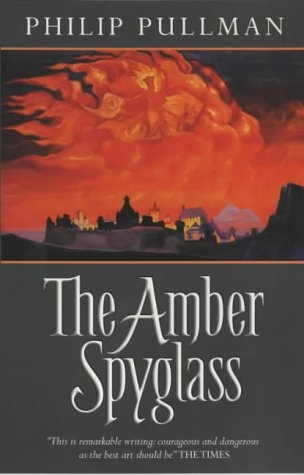

When Philip Pullman's novel, The Amber Spyglass, became the first children's novel to win the Whitbread Prize, in 2002, adults discovered what children had already known for a while: that the His Dark Materials trilogy was excellent escapist literary fiction for readers of any age. The books even have the author's black and white line drawings as illustration, making them entirely a work of art in their own right.

|

|

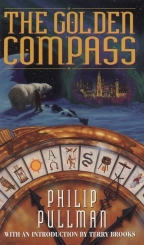

...and the kid's paperback version. I'm missing the adultness or kidness of the cover art, but the differing covers offer book colelctors a bonanza of possibilities. |

Pullman had been writing novels for children since the Eighties, but it was Northern Lights (1995, Carnegie Prize winner), The Subtle Knife (1997) and The Amber Spyglass (2000) which made his writing headline news; suddenly the trilogy have become the thinking man's Harry Potter, and there's even talk of a film, with Tom Stoppard writing the screenplay, and Nicole Kidman as Pullman's choice for the beautiful, wicked Mrs Coulter.

|

|

Philip Pullman is something of an engimatic character. |

As I have said before, the hallmark of a good and believable fantasy is that it interposes elements of the familiar and the unknown, thus giving the reader a framework he can understand as well as a whole new world to discover. A lot of books, especially for children, begin with a search and a journey; it gives the book a tangible direction from the known into the unknown, and allows the story to develop along comfortingly familiar lines. Pullman, however, allows himself no restrictions, and it works spectacularly well. Significantly, in an interview with the BBC, Pullman said "The fantasy elements are there to help me say more about being a human being".

|

|

|

Pullman has become something of an enigmatic character; not content with debates over his novels, he sparked yet more controversy by saying that no-one should teach them until they were over the age of thirty-five. His arguments are plausible, but with the current deficit of teaching staff, unlikely to be heeded! A librarian and then a teacher after studying at Oxford, he has experience of what children and adults want to read and to learn about, and he has hit the mark perfectly, not only with His Dark Materials, but with his previous novels, including the Sally Lockhart novels, The Ruby in the Smoke, The Shadow in the North and The Tiger in the Well, about a tough female Victorian detective and the cases she deals with. Sally Lockhart and her companions are how we imagine the heroes of His Dark Materials will grow up; uncompromising, gritty, not always that friendly, but real people, with compassion and understanding. In interviews relating to the trilogy, Pullman says that he sees himself as a part of a story-telling tradition that began with Homer and includes Milton, Blake, Swift and Dickens. There are certainly elements of all these writers in his work, notably the characterisation of protagonists and the vivid incarnations of cities and landscapes in His Dark Materials.

|

|

|

The trilogy begins with Northern Lights (The Golden Compass in the US), where we are introduced to some of the main characters of the trilogy, and to an intriguing world that is ours, and yet not quite ours. It begins in an Oxford college (where better, said one critic, for a fantasy to begin, than such an unreal place?) Twelve-year-old Lyra Belacqua lives with her uncle, who is master of the college, playing with children in a city haunted by the spectre of child snatchers, who, rumour has it, carry out unspeakable scientific experiments on children. One of the remarkable inventions of the trilogy is that of the dæmon, an animal that stays beside its human as an outward projection of the spirit of its owner. Through Lyra and her dæmon, Pantalaimon, we learn about the principle of the dæmon, that it changes shape until a child is grown up, when it takes a permanent shape; and that there is a bond between human and dæmon which cannot allow too much distance between the two without severe pain. Pullman has emphasised that one cannot choose the shape one's dæmon takes, but that he would like his to be a dolphin, for intelligence and agility.

When her best friend is snatched, Lyra and Pantalaimon travel to the North in search of the missing children, and encounter armoured bears, witch clans headed by the beautiful and terrifying Serafina Pekkala, and a fight for survival that forces Lyra to search herself for her greatest fears, and eventually to leave her childhood behind.

As she visits other worlds and cultures, she learns to understand herself and human predicaments; Pullman himself has said that the many worlds theory is a gift to story-tellers, and that all that is needed is a method, such as Alice's looking-glass and Lewis's wardrobe; here, it is the knife.

|

|

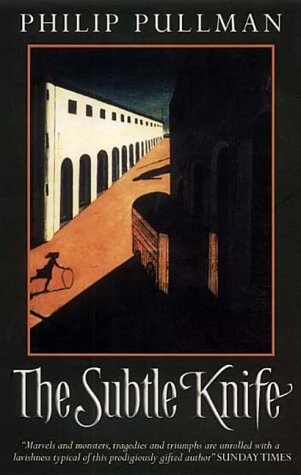

This is reputedly Philip Pullman's favorite cover for 'The Subtle Knife'. |

In The Subtle Knife, we are introduced to Will, who lives in yet another world, not unlike our own. Like Lyra, he too has issues of his own to work out, and when he finds his way into another world and meets Lyra, their adventure continues together. They find themselves in the city of Cittàgazze, surrounded by angels and haunted by Spectres, which eat the souls of humans. As children, however, they find that they are safe from the Spectres, and they search the city until they find the precious knife, which allows them to cut through into other worlds. But this in itself has its own dangers, which they discover at the end of the trilogy. The search for these things is not dissimilar to a Grail-quest, a notion that permeates fantasy novels from Tolkein onwards. In this novel the children discover the true purpose of their quests, and the novel ends with a cliffhanger, which left many readers waiting for nearly three years.

|

|

No need to feel embarrassed buying this UK edition in an 'adult' cover. Who ever thought that the word "adult" would have good connotations? |

This novel also sees the consideration of Dust, which the theologians of Oxford had debated in the first novel. Much of the trilogy is concerned with the children's desire to understand these things, and in fact they reach a clearer understanding than the representatives of the church and academia, because Dust is something pure, innocent, something which enables the world to survive but which must, in turn, be protected. To quote Pullman, who puts it much better than I can, "The relationship we have with Dust is mutually beneficial. Instead of being the dependent children of an all-powerful king, we are partners and equals with Dust in the great project of keeping the universe alive...I don't find it difficult to think that Dust might suggest a new kind of relationship with God."

|

|

Milton's classic informs Pullman's Northern Lights trilogy. |

The trilogy is prefaced by a quotation from Milton:

"...Unless the Almighty maker them ordainHis dark materials to create more worlds".

The ideas of Miltonic religion and laws of nature are explored in the trilogy, where theology is a science, considering higher powers and the laws that govern the world in which they live. Good and evil, right and wrong battle throughout, and what seems good is not always so; it's an informative moral framework for children, but it also raises questions for adults. Pullman believes that writers have a moral duty to tackle the big issues, and his choice of Paradise Lost as a source of inspiration for quotations and theories is fascinating; Milton was controversial in the 1600s when he was writing his quasi-political epic about the fall of Satan from heaven and the subsequent fall of man, and Pullman's exploration of similar issues has equally proved controversial. The existence or nature of God, or Authority, is the fundamental issue here, and Pullman expresses this in a delightfully subtle manner, considering vast and complex issues within a highly readable story.

|

|

The final book in Pullman's trilogy in the UK adult edition. |

The Amber Spyglass has a particular duty as the last in the trilogy; to tie up the ends, to provide some answers, and to transmit a sense of completion and understanding to the reader. By far the longest novel of the three, it encompasses more worlds than ever before, with romantic landscapes and characters such as Kendal Mint Cake-eating angels. Lyra now has in her possession an alethiometer, an instrument like a crystal ball in function and purpose, but entirely scientific, and able to be understood only by chosen people, of whom Lyra is one, although it takes her a while to tune in to it. For those wishing to pursue this fascinating instrument, there is now a detailed description of it to be found at www.randomhouse.com/features/pullman/.

In The Amber Spyglass, the hero and heroine are suffering the trials of young adulthood, with its accompanying responsibility and loss of innocence, which is particularly highlighted when they visit the world of the dead. The strong characterisation allows this to develop effectively and ensures that the reader really cares, and notices, what happens to Will and Lyra, and their developing relationship is an intriguing aspect of this final novel.

It is in The Amber Spyglass that we can see what went wrong in previous worlds and civilisations, why religion can turn on the people, and what values we should hold on to. It is also here that we realise that there will be a second fall, and a second coming, a kind of spiritual rebirth where a true and good order will be restored, and children's innocence will be preserved and the world we be a united and happy place. Milton would have been proud; this is an epic for the twenty-first century.