Children, Crime and Consequences

The Agony Column for July 18, 2003

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

|

|

Douglas Coupland's art work, 'Tropical Birds': "The

instant the fire alarm went dead, Motte heard a strange,

almost surreal sound welling up faintly from inside, like

birds chirping. Across the cafeteria, telephone pagers in

the abandoned backpacks were going off, unanswered calls

from desperate parents."

from the Rocky Mountain News.

|

It took me years to admit to myself that having children had

changed my reading tastes. No longer was I ready to read the kind of

horror that gleefully folded, spindled and mutilated kids along with

adults, pets and evil monsters. Slowly but surely I got a lot pickier

about what I read. But old habits die hard, and as my charming

children mutated into teenagers, I found my threshold rising. No, I

don't think that I could read 'Cujo' again. There are still some

books that I can't bring myself to read, no matter how well liked or

highly recommended they come. But through a recent aberration, I

found myself reading a lot of recent titles that did involve children

in danger and children in the vicinity of crime. It's a genre with a

lot of potential -- to appeal or repel. Sometimes both at once. It's

easy to have mixed feelings.

|

|

Henry James plays on the ambiguous perceptions we have

of children in 'The Turn of the Screw'.

|

Now, it's not as if this is a new development. Literature about

children in terror has been used to terrorize children for years.

It's a part of the curriculum and as it happens one of the more

enjoyable slabs of literature shoved down the throats of kids in

school. For myself, I found the touchstones of school-lit terror to

be Henry James 'The Turn of the Screw' and William Golding's 'The

Lord of the Flies'. Henry James' novella was actually the first of

these I encountered. Despite its short length, 'The Turn of the

Screw' actually maps much of the terrain for much of the

child-oriented literature of terror to follow. James is such a

masterful writer that even now, over a hundred years after its

publication, critics are finding nuances that were not obvious. For

me, 'The Turn of the Screw' was a revelation of the power of

ambiguity. Miles and Flora, the two children of Bly are beautiful

blanks upon which the reader, the governess, Douglas and James are

able to project pure goodness and incisive evil. Miles and Flora are

in a quantum state, fluctuating between good and evil from scene to

scene, from reader to writer to narrator. Are they leaking evil or

being polluted by it? James does with children characters what cannot

be done with adults. Adults are finished; they're grown. Children, on

the other hand, may change rapidly, from moment to moment and extreme

to extreme. Are the "ghosts" seen by the governess projections of the

children, or are they affecting the behavior of the children? Are

they working with the children? James' powerfully simple language and

plotting enable him to use the children as portals for a frightening

number of both hopes and fears. If you haven't yet read this novella,

take the time to do so and see where much of today's finest horror

and suspense literature first found a small child's voice.

|

|

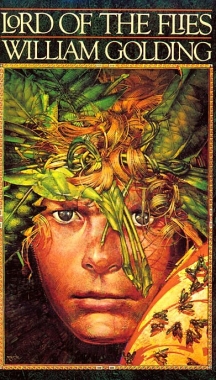

I had to turn off a recent and very accurate movie

adaptation of this novel.

|

'The Lord of the Flies' pursues another path, just as powerful,

but more directly disturbing and unpleasant. William Golding is

working for something of an opposite effect of James. 'The Lord of

the Flies' puts children in a situation where they are forced to

behave like adults -- or die. It's a frightening and simple formula

that has been copied relentlessly and exploitatively. The original is

still too unpleasant for many a parent to experience. By forcing

children to take on adult behavior, all the horror of that which is

accepted in adults is emphasized by the children. The ugliness of

politics becomes an analogue of bullying. Douglas Coupland recently

told me in an interview about a series of Canadian public service

announcements in which adults are portrayed in the manner of

schoolyard bullies. A man in a suit is shown getting his lunch taken

from him by office bullies, or pushed out of a queue for a train. The

point is that this behavior is unacceptable for adults and should be

unacceptable in children as well. 'Lord of the Flies' reverses that

thought and shows that acceptable behavior for adults is unacceptable

and disturbing when seen in children. The creation of civilization is

an ugly process when seen in miniature. Killing is a lot worse when

it's children killing children as opposed to adults killing adults.

'Lord of the Flies' retains its power because it boils the evil that

men do down the evil that children do.

|

|

Machen tapped into the terror of illogic in his story

'The White People'.

|

Arthur Machen, a noted horror writer, also paved the way for

children and evil with his powerful story 'The White People'. Unlike

James and Golding, Machen tells his story from the point of view of

the child. After a brief and very Victorian-style introduction, the

bulk of 'The White People' is the chilling diary of a 13-year old

girl. One day, like all children, she ventures beyond the confines of

her safe world into a world of Faerie. Related in a nearly unbroken

stream of consciousness, Machen's meditation is a powerful picture of

innocence faced with a pure evil, an evil of illogic, an evil of

things that cannot and should not exist. Machen makes excellent use

of a narrator who is experiencing events she cannot quite comprehend,

though she can describe them all too well. Few since have described a

slow conversion from innocence to evil without any recognition of the

process taking place as well as Machen. Guided by a beloved but

sinister (to the reader) "nursie", the narrator experiences anomalies

with expectation. "And there were other rocks that were like animals,

creeping, horrible animals, putting out their tongues, and others

were like words I could not say, and others like dead people lying on

the grass. I went on among them, though they frightened me, and my

heart was full of wicked song they put into it; and I wanted to make

faces and twist myself about the way they did, and I went on and on a

long way till at last I liked the rocks and they didn't frighten me

any more." Though there's a strong supernatural element to 'The White

People', it speaks to a timeless corruption within innocence. It's an

upsetting perception of reality that can bring out the best in

talented writers.

|

|

Jack Womack told me to read this novel of his first.

It's a powerful evocation of a corrupted childhood in a

world frighteningly close to ours.

|

My most recent bout of child-related reading began with Jack

Womack's 'Random

Acts of Senseless Violence'. Womack's vision of a pre-teen girl

who grows into a violent -- but still likable -- killer is even more

powerful now than it was when it was written. Womack created a vision

of the near future that seems contemporary and compelling even though

it was written some ten years ago. But it's the voice of his

narrator, Lola Hart, and her perceptions of her family that lifts

this novel into the stratosphere of fine literature. Lola Hart is a

12-year old girl living with her nuclear family -- her

barely-employed father, her drug-addled mother, and her distant young

sister in a New York on the verge of financial collapse. In the

course of the novel, the Harts lose their small but nice apartment

and are forced to move to a slum, where Lola begins her education in

street life. Womack plays out a voice that reads like a combination

of that of the young girl in Machen's 'The White People' and Alex

from 'A Clockwork Orange'. The world he portrays is our own skewed by

just a couple degrees of chaos and filtered through Lola's changing

eyes. Womack effortlessly captures the changing voice and attitude of

Lola as she finds herself changing to match her new surroundings. He

carefully reflects the apocalypse without by the changes within.

Escalating world events begin in the sidelines but quickly come to

occupy center stage and serving to propel the plot. 'Random Acts of

Senseless Violence' uses a child's voice to describe an adult's

world. It breaks your heart as it tells you how it works.

|

|

Mark Haddon's wonderful novel 'the curious incident of

the dog in the night-time' will easily make lots of year's

best lists.

|

Having read 'Random Acts of Senseless Violence', I became

intrigued by the idea of children's place in crime fiction. Yes, I

know 'Random Acts of Senseless Violence' isn't exactly crime fiction,

but that was the phrase that came to me, especially when I first

heard about 'the curious incident of the dog in the night-time' by

Mark Haddon. We have two reviews of this novel, both by myself

and by Terry

D'Auray. We both immensely enjoyed Haddon's masterful novel,

though our takes on why are rather different. But Haddon has utterly

nailed the appeal of the youth in a tale of crime in his first novel

for adults. This novel has a tremendous potential to become a

bestseller, and it deserves to be one. It's funny, touching, powerful

and dense with facts and speculations. The uninformed observations

from a child not capable of emotional connection of the adult world

manage to make everything old new again. Most importantly, it's just

totally readable. Few who pick it up in the store will go home

without it. Haddon's narrator, the 15 year-old Christopher John

Francis Boone is a character that the reader will adore being around.

This brilliantly written, very thin novel will remind you once again

of why it is so much fun to read.

|

|

If you can find a first edition of this novel, it's

worth looking at. Even the US paperback includes the

illustrations fro the hardcover, however.

|

As I was reading Haddon's novel, I was remembering a very

different novel with a very similar title from last year. I didn't

remember the title or author, but I remembered the bookseller who had

recommended it, Michael DeSarno of Legends books. I gave him a call

and as much of a hint as I could and he pointed me to Chloe Hooper's

'A Child's Book

of True Crime'. He still had first editions, so I ordered one up.

Published without a dust jacket, it features a lovely illustration

and a nicely textured surface. It's definitely a book worth owning

for the format, which includes interior illustrations as well.

Hooper's novel is a bit of a mixed bag, depending on your feelings

about erotic literature. Her tale is narrated by a hot-tot-trot

teacher who's having an affair with the father of one of her

students. The man's wife has just written a true crime work about a

jealous wife who brutally murdered her husband's lover then killed

herself -- or perhaps disappeared. When the student's drawings start

to hint at violence, the teacher begins to imagine that she's got

herself into a bad situation.

It's a brilliant setup. Hooper's prose is strong and there are

lots of quotable portions of the narrative. Hooper fills the novel

with fascinating facts about children and violence. Even more

inventively, she writes a children's book that is interspersed in the

narrative, in which cuddly animals try to determine the culprit to

the true crime. She gives the children a strong voice, recounting

discussions about God, life and death that seem authentically

child-like. But her narrator is a bit addled by her attraction to the

father, and the portions of the narrative that follow their

potentially fatal attraction to one another serve only to soften the

focus on the discussions of children and evil. Now, the production of

the first edition of this novel is nothing short of wonderful, and

the questions it raises regarding children's perceptions of violence

and evil are fascinating. The illustrations for the children's novel

are delightful. I'll look very closely at Hooper's next novel. If she

continues to indulge her inclination to the erotic, then I may give

it a pass; if she follows up on her predilection for facts, I'll be

springing for it straight away.

|

|

Laurie King's 'Keeping Watch' contains the origin

story for a character who protects children in danger --

even if they're in danger from other children.

|

Laurie King is noted for a couple of series of detective novels,

but her most recent novel, 'Keeping

Watch' takes her in a new direction. Following one of the

characters from her novel 'Folly', she plays int he same subject as

Henry James, and does so remarkably well. 'Keeping Watch' was a novel

I actually might not have elected to read had I not been asked to

interview the author, as the subject matter is ont he dicey side of

what I think I can tolerate. Allen Carmichael is a fairly wrecked

Vietnam veteran who specializes in rescuing children from abusive

parents. King does an excellent job of creating a man who has been

over the edge and returned able to face situations that many people

-- including myself -- can't face, even in fiction. She describes

with fascinating detail a sort of "underground Railroad" for abused

women and children. She then sends Carmicheal on his resuce mission

-- only to find that the child he may have rescued may be more

dangerous than the abusive father he was recused from. Likie James,

she plays with our ability to perceive a child as a victim one

second, then a perpetrator the next. It's a gripping tale of terror

that never goes so far into pathos as to have the reader rendered

into hopeless sorrow. King plays fair with the mysterious aspects of

her story while giving her characters room to grow and come to life.

It is on the mystery side of the genre gap, but only barely. 'Keeping

Watch' demonstrates that King is capable of mining depths without

plumbing them.

|

|

Alice Sebold tapped into the mainstgream consciousness

with her novel 'The Lovely Bones'. But that doesn't mean

that I can actually make myself read it.

|

I mentioned earlier that there are books I just can't bring myself

to read. Amongst those is 'The Lovely Bones' by Alice Sebold. I met

her while I was interviewing her husband, author

Glen David Gold whose novel 'Carter

Beats the Devil' I just adored. Ms. Sebold was very nice and

wonderfully astute. We talked a bit about the use of supernatural

themes in more mainstream novels, and she suggested some fascinating

books for me to read. I really, really intended to read her novel.

Terry D'Auray went so far as to loan it to my wife and I. But knowing

what was between the covers, I decided to give it a pass. I've been

in the vicinity of events remotely resembling those she describes;

the rape and murder of a teenage girl, and the slowly unraveling

family life that follows. Judging from Terry's

review, I think I made the right decision. While I know for a

fact from both Serena's

review and Terry's review of this novel that it's a powerful and

well-written piece, I also know that the painful place it inhabits is

someplace I can't go as a reader. Make no mistake; when Alice Sebold

writes another novel I'll be first in line. You can also make no

mistake that this novel develops the themes of children, crime and

consequences with a power and craft that's the reading equivalent of

being hit upside the head with a sledgehammer, as artistically as

humanly possible. And make no mistake that if you've not known a

crime victim, you would find this exploration searingly informative.

But if you expect to read this novel and not be moved far beyond your

normal emotional boundaries -- that's a big mistake.

|

|

Coupland's cover evokes the dots and lines behind the

faith of children.

|

Yes, embarrassingly enough, I did ask Douglas Coupland about the

slight similarities between 'The Lovely Bones' and his latest novel,

'Hey

Nostradamus!'. He was lightning quick to correct me; 1), 'Hey

Nostradamus!' was in the mail to the publishers before 'The Lovely

Bones' was released (no surprise there, but) 2) "You haven't read my

other novels, have you?" [Uh, no.] "I've used dead teenagers

as narrators before; this isn't the first time." 'Hey Nostradamus!'

begins with the post-life narration by a 16 year-old girl of a

Columbine-style massacre that takes place in 1988 in a Vancouver high

school. From the beginning, Coupland uses his teenage narrator to get

directly to issues of faith in a way that would not be possible were

she an adult. Her thoughts are a fascinating combination of

matter-of-fact acceptance and naïve belief in the love she

shared with her boyfriend, Jason, to whom she was secretly married.

Coupland leavens his narrative of tragedy and terror with a good deal

of black humor, rendering the novel readable where otherwise it might

not be, by me at least. He also pursues his story in a unique

fashion. He ignores the perpetrators and the police and follows the

victims of the crime. The novel's next section finds Jason, eleven

years later in 1999, leading a rootless but not entirely unhappy

existence. The next section traces the life of Heather, who has tried

to love Jason and become a part of his life. The final section, an

elegiac coda, brings the reader back to Jason's father. Beautiful,

funny and moving -- without ripping out your heart -- 'Hey

Nostradamus!' is a searing look at faith and the lives of the victims

of child-crimes.

All that innocence, wasted, calcified by terror into an acceptance

of the undeniable awfulness of this life. Children who perpetrate

crimes, who are the victims of crimes, children who solve crimes --

there's a howling abyss beneath the flat recitation of what happened.

It's delicate territory, but in the hands of great writers, putting

children in harm's way is the author's way of preventing the horror.

By writing about it, by committing it to paper as fiction, it remains

firmly in the realm of the unreal. We can assimilate it -- or not --

and be changed by the knowledge. Reading can be one of the most

powerful experiences we humans can have. Sometimes we need to pass a

work by, to acknowledge its power but leave it undisturbed. Maybe

someday I can read 'The Lovely Bones'. But not while my kids are

still teenagers.