The Agony Column for August 22, 2003

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

|

|

I bought this book in 1983, but it turned out that the monster was a gas-filled garbage bag animated by the spirit of a pet frog. I was crushed. |

By the time it burned itself out in the 1980's, the horror genre had become a monolithic entity, single-minded in appeal, content and presentation. The gerund title, the foil letters, the obligatory splatter and redemption -- who could have guessed that thrilling fiction could get so predictably boring?

Well, probably anyone who has attended a marketing meeting.

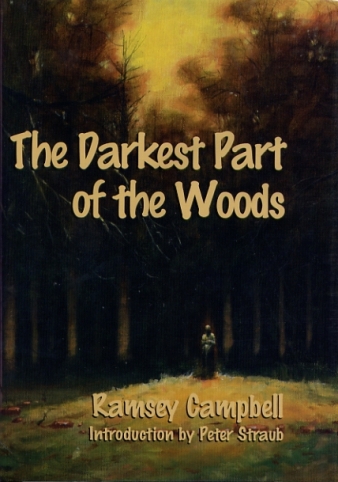

Since then, horror has gone into hiding. Stephen King novels are shelved with mainstream fiction -- no surprise, since at this point, they are mainstream fiction. The horror genre section has disappeared from many bookstores, and if it's there, it's the same old suspects -- King, Koontz, a smidgen of Barker and Straub, more Bentley Little than you'd expect, 'Dracula', 'Frankenstein' and maybe if you're really lucky, M. R. James.

It was only terror, the finest emotion of fear that brought back horror. In the wake of the events of September 11, 2001, our willingness to experience fictional fear was pumped up by the omnipresence of actual fear. It's as if we're in training to be afraid. But horror fiction hasn't been resurrected with the same old set of monsters and closets. The best writers out there are writing horror now, and they're not just the usual slumming literati. These are writers who have come round to understand that the finesse required to create terror offers both readers and writers opportunities for expression, exploration and enjoyment that simply cannot be found in fiction without fear. Many aren't intentionally writing horror; it's just a byproduct. The literary terrors are taking readers into themselves, letting them gaze upon their own demise and the aftermath, bringing on the pleasurable frisson of fear without the side order of guts in a cup. What these writers are realizing is what horror readers and writers have been saying for ages; that the best writers in the English language have written horror and terror fiction. They've made the intuitive leap from the idea of slumming in a sleazy genre to the thrill of writing without restraint. If it's good enough for Henry James, how can you call it slumming?

To find the literary terrors who are undermining our morality while entertaining the hell out of us -- literally -- you'll need to look a little harder than you might have had to in the 1980's. You'll have to dig through fiction, through mystery, fantasy, and even through non-fiction to find the best and brightest in this brief bloom of fear. Your personal search for terror will be rewarded with some of the best reading you'll find this year.

|

|

Dorian Gray for the new millenium. |

You won't have to look very far to find Chuck Palahniuk's 'Diary'. Last year in his interview for Agony Column, Palahniuk avowed that he was going to enter the horror genre. He already had, at that point with the over-the-top terror of 'Lullaby'. Even the most sympathetic reviewer -- that would be me -- has to admit that the subject of crib death might be a little too difficult for readers to handle. In 'Diary' Palahniuk doesn't back off in the least, but he shifts focus from crib death to painting. The result is that the novel is a good deal more approachable, but no less severe, a sort of 'Portrait of Dorian Gray' for the new millennium; of course the subject of the portrait is a Small Town With A Secret. 'Diary' is going to receive a lot of attention. It will be piled up in bookstores, reviewed by every major newspaper. A major online magazine has already published a frothing review of the sort that recommends a novel by virtue of its virulent dislike. Palahniuk may have approached the review-proof stage of his writing career. I remember first hearing Philip Glass and thinking that his music was simply the output of a Roland synthesizer's arpeggiator played by a symphony orchestra. There are still people who think that, but like as you might, it's clearly not the case. And anyway, that proves to be a rather inspired idea now, doesn't it? Just as Palahniuk's 1999 title 'Survivor', with its crashing plane and religious cults seems creepily inspired in the aftermath of the events of September 11, 2001. 'Diary' may be a horror novel but in terms of narrative technique, it's without equal. Sure it might look or sound simple, but that's Palahniuk's craft -- invisibility. A quick analysis of what's happening in the narrative will plunge the reader into a wonderfully complex hall of mirrors. 'Diary' is simply an example of a writer using the toolkit of horror to build a very complex novel.

|

|

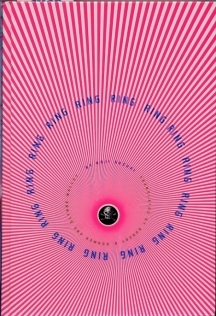

Look deep into my eyes. You are beginning to feel drowsy. There is nothing wrong with your television set. |

Using a similarly simple narrative, Koji Suzuki brings an equally complex web to life in 'Ring'. Vertical-Inc.com has translated from the Japanese and brought us the first of three novels that spawned small-screen and big screen hits on both sides of the Atlantic. As usual, the book is better. 'Ring' frightens the reader as if it were a horror novel but does so using not just the horror toolkit, but the mystery and science fiction writer's implements as well. Like Palahniuk, Suzuki is concerned with the effect of the media-drone on the intellects and consciousness of those bombarded by it, and he's concocted a very M. R. Jamesian ghost to haunt our televised world. If you're going to find 'Ring', you'll have to dig, and I can't exactly tell you where you're going to need to look; it may show up in general fiction, it could show up in science fiction, and some astute but ultimately misguided soul may actually file it under horror, assuming there's a horror tab to file it under. It won't be hard to find if you can see the cover however; Chip Kidd has designed a literally hypnotic optical hallucination to suck you into the void.

|

|

A pristine first edition of the 1989 classic that still rings true. |

Kidd isn't any newcomer to this new world of terror. In fact, back when many of my readers may have been cracking their first H. P. Lovecraft collection, he designed the cover of a book that looms large in today's landscape of non-generic horror. Katherine Dunn's 'Geek Love' is a towering monument to what happens when a writer takes the tools of horror seriously and without condescension. First published in 1989, 'Geek Love' tells the story of the Binewski's Fabulon, a freak show like no other. Lovingly created, lovingly raised by Al and Lil, the Binewskis are a family of flipper-boys, Siamese twins, tail-girls and the apparently normal Fortunato, whose inner freakishness proves to trump all outward appearances. Dunn was so far ahead of her time that they're only now actually diagnosing a "global pandemic" of Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD). Victims of BDD feel their bodies are imperfect and must be corrected, often with surgery. The best-known manifestations of BDD are eating disorders such as anorexia and bulimia and, notoriously, individuals who have healthy limbs removed because they view them as ugly or extraneous. Doctors are now suggesting that the only current cure for BDD is in fact amputation, if that's what the patient wishes. Arturo the Flipper boy would be proud -- or annoyed that he wasn't getting any of the gate for this deliciously creepy disease. Those who have been waiting for a follow-up can take heart; Chuck Palahniuk, in his Portland travelogue, 'Fugitives and Refugees' takes great pains to point all the places in which Katherine Dunn lived and worked while writing 'Geek Love', and assures readers more than once that she's working on a new novel.

|

|

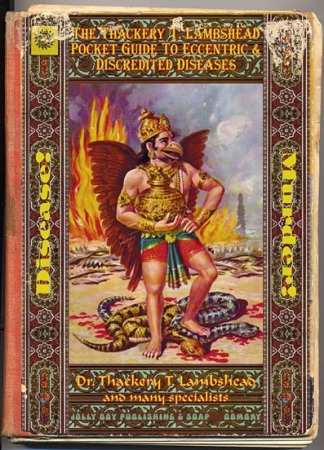

John Coulthart's to-die-for faux Guide cover. |

Disease -- as in unease -- gets the meta-fictional treatment in Jeff VanderMeer and Mark Roberts' 'The Thackery T. Lambshead Guide to Eccentric and Discredited Diseases'. VanderMeer and Roberts have come up with a brilliant idea for an anthology. The Guide features the contributions of more than 40 writers, each of whom has created an imaginary ailment, and sometimes even a cure; which might be worse than the disease. The life of the "original author", Thackery T. Lambshead provides a connective tissue to keep the focus of the reader amidst this riot of vibrant imagery. The authors have sabotaged the gruesome gore they occasionally employ with deft humor and pithy wit. The instructions for this are simple; shake, shiver and laugh. Repeat as required. Self-medication is definitely the cure here, and I'm not just saying this because I'm in the book. VanderMeer and Roberts have created a work of fictional non-fiction horror. If it sounds paradoxical, that's because it is; if it sounds fun and funny, that's because it is. Yes, you can take everything I say with a grain of salt because I can't pretend to be objective about the Guide. But it should be amply clear that Jeff VanderMeer has once again managed to create something out of nothing, gone boldly where no man has gone before. Where will you find the Guide? Look for it from Booksense bookstores everywhere, or you can pre-order from NightShade.