The Agony Column for October 29, 2003

Commentary by Serena Trowbridge

A portrait of Chaucer from the Ellesmere manuscript

of The Canterbury Tales.

The British public is in the throes of a long and serious love affair with history. It is hard to tell when and how this started, but the media, books, theatres and dinner parties across the UK are full of it. Publishers are indicating that historical and Gothic romances are back on the agenda. Simon Schama's History of Britain series have topped the bestseller charts for many months, and the parallel series on television have had rave reviews. This more academic interest has become popularized for the masses in the form of made-for-television films on Boudica, Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, among others, and the gorier and bawdier, the more the public loved them. The BBC's Big Read opened people's eyes to the fact that this is a desire that literature can fulfill, and this public demand has been fulfilled by, of all unlikely candidates, Chaucer. Let's face it, most people don't read Chaucer, although they may have heard of The Canterbury Tales. Some experienced a tale or two at A-level, but this is frequently off-putting and often does little for Chaucer's popularity.

|

|

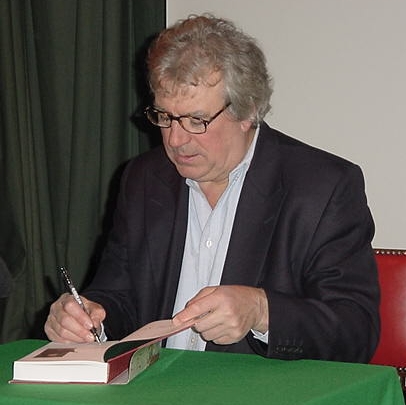

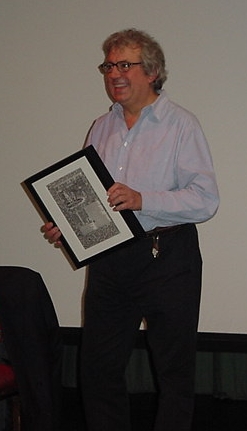

Terry Jones signs copies of 'Who Murdered Chaucer?' his latest work in the UK. |

However, a well-timed series of events has put Chaucer firmly back on the map of the British reading public. The most universal of these events has been the BBC's Canterbury Tales, a series of six of the tales updated by writers for modern times. These have been well received and are indeed Chaucer for the twenty-first century, including Julie Walters playing the Wife of Bath as a sexually voracious aging actress who falls in love with a much younger man, and Jonny Lee Miller as a sinister psychopath after money and fame in The Pardoner's Tale. The delight of these tales has been that everyone (or everyone I know) has watched them, because they are, quite simply, modern drama. They are closely based on the tales, but they emphasize the modernity of Chaucer's themes - lust, avarice, sexual power, family values, and many more. I went to a BBC workshop where I met Olivia Hetreed, who adapted The Man of Law's Tale, a tale of alienation, xenophobia and Christian values, as the story of a young refugee, Constance, who is washed ashore in Britain. There are certain things, she says, such as the value of virginity, which are not so relevant to contemporary society, but in many ways things haven't changed and people have the same values and desires as in Chaucer's world, which makes the tales a delight to adapt. The BBC is now running a writing competition to adapt the tales for radio, and a great deal of information about Chaucer is available on the BBC website.

|

|

Peter Ackroyd captures the feel of The Canterbury Tales in his heavily researched novel 'The Clerkenwell Tales.' |

Fortuitously (or probably deliberately!), Peter Ackroyd's 'The Clerkenwell Tales' was released shortly before the BBC programmes commenced, and also serves to highlight the relevance of fourteenth century issues to modern society. Terrorism, fanaticism, political greed and public rumor are all displayed by the characters in this novel, and it is quite alarming in its parallels with modern society. Ackroyd has built a picture of medieval life in London, using the building blocks of individual lives, from the high to the low, and it is rich, strange, irresistible reading, and an appropriate tribute to Chaucer's work. Ackroyd remains true to Chaucer's language as well as his concept, using medieval notions of language, descriptive, vivid and colorful as well as alliterative, which not only evokes the spirit of the period but also is useful for disguising the words that Victorian scholars chose to leave out of their translations, considering them unsuitable for the general public! It seems sadly unlikely to me that this novel will prove as popular with the public as the BBC's adaptations have, but it is nonetheless a delightfully enjoyable way to access the sense of Chaucer's work as well as to appreciate the background of Chaucer's London. It is in many senses a scholarly work, into which great amounts of research have clearly gone - in the way that the popularized BBC versions are not - but hopefully many viewers will be led to this novel as the interest in Chaucer increases. It is well worth the trouble, evoking every aspect of fourteenth century London as well as the atmosphere of the tales in a highly readable and enjoyable format.

|

|

Terry Jones' first stab at Chaucer was this portrait of a medieval mercenary. |

If these insights into The Canterbury Tales have inspired you to find out more about the man himself, I am certain that the best place to start is with Terry Jones' book, 'Who Murdered Chaucer?' Terry Jones is most famous for Monty Python, but has reinvented himself as one of Britain's Chaucer experts, and this is his second book on the subject, following on from Chaucer's Knight. He is also preparing a series on the lives of medieval figures for the BBC next year. You can find out more about his work at his publisher's website.

|

|

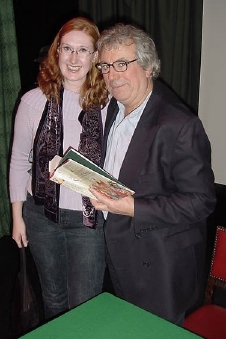

Critic Serena Trowbridge met Terry Jones at at event for his latest work, 'Who Murdered Chaucer?' |

I went to an event as party of the Birmingham Book Festival at which Terry Jones talked about his latest book (see photos - courtesy of a nice man called Mike who had a camera with him!) Terry's knowledge of the fourteenth century, its political and ecclesiastical unrest and the literature of that period is impressive, and he talked for an hour with huge amounts of energy and enthusiasm, and, equally impressively, without any notes, just a slightly temperamental projector with a series of relevant pictures. His manner is that of an extremely enthusiastic and unusually humorous university lecturer, which went down well with the audience. Even his rendition of Middle English quotes was perfectly delivered, and since he picked a couple of rude ones, also raised a few laughs.

|

|

Terry Jones' "wasitdunatall" investigates the disappearance and death of the provocative writer. |

The book is, he says, not so much a whodunit as a wasitdunatall?! The book began in 1998, when he and some fellow academics met to hold an inquest on Chaucer's death, 600 years after the event. This proved so interesting that it was decided between them - Terry Jones, Robert Yeager, Terry Dolan, Alan Fletcher and Juliette Dor - that they should each go away and write a chapter for a book about the death of Chaucer. Terry's turned out to be by far the longest, however, and the others agreed that their work might be subsumed into his. He admits, however, that had he known how much work it would have taken he would never have started it! Terry had been harboring suspicions about Chaucer for years, he said, and had been drawn to further study of his work and life after his studies in English Literature at Oxford, where he produced some work on Chaucer and felt that "he was such an interesting guy but the boring bits needed investigating."

|

|

Director of Birmingham Libraries presents Terry Jones with a framed picture from the Kelmscott Chaucer. |

One of these boring bits is his death. Chaucer's tomb states that he died on 25th October 1400, but the tomb dates from 100 years after his death and is nearly illegible. Basically, Chaucer vanishes, along with all autograph manuscripts. The detective work that has gone into the work was fascinating, including examining manuscripts all over the world for signs of tampering. Terry outlined his argument in an altogether convincing manner (see review), and, despite apparently little hard evidence and a distinct lack of a body, his case seems very convincing. He also has the happy knack of highlighting modern parallels, for example comparing Henry IV's war against heresy with Bush's war against terrorism. I was also interested to see Terry's depth of knowledge in the history of entertainment - the book has a great deal of information on entertainment at court and the history of reading, and reading aloud, which obviously has interesting resonance in his own life. At the end of his talk, the Director of Birmingham Libraries presented Terry with a framed picture from the Kelmscott Chaucer, with which he seemed delighted (see photo).

|

|

Jones with the picture from the Kelmscott Chaucer. |

'Who Murdered Chaucer?' is not just about Chaucer's death; it is primarily about his life, and the times in which he wrote, giving tremendous insight into the man that Chaucer was as well as his work. Given its view of the fourteenth century, both panoramic and specific, it makes the ideal companion to Ackroyd's 'The Clerkenwell Tales' as well as to Chaucer's work itself.

Interestingly, a member of the audience asked him what he had thought of the BBC's Canterbury Tales. His answer was that really they had nothing to do with Chaucer, since Chaucer took his basic stories from other writers, including Boccacio (as did Shakespeare), and that the artistry lay in the writing and satire rather than the plot. Having said that, the BBC had therefore done exactly what Chaucer did, which was to appropriate a good yarn and adapt it for the contemporary audience, and from that point of view it had worked extremely well.

|

|

A positively ancient copy of Dan Simmons' novel 'Hyperion', an SF masterpiece that draws on Chaucer's work. |

There are other novels about based on The Canterbury Tales, since it is such a rich source for writers. One such novel is Hyperion and The Fall of Hyperion, by the sci-fi author Dan Simmons, whose latest offering is Ilium, based on The Iliad. Hyperion tells the tale of a group of travelers who are part of the Hegemony, a fascinating but self-destructive civilization, going to Hyperion, telling tales of their life as they travel. I have to admit that this is one I just haven't had chance to read, but it has received excellent reviews and is a fascinating new twist for the ongoing rejuvenation of Chaucer. The book won the 1990 Hugo Award for Science Fiction. Reviewers have described it as romantic, violent, supernatural, full of political and spiritual intrigue - in fact, not unlike The Canterbury Tales themselves. You can find out more about this fascinating book at Dan Simmons' website.

Perhaps it is nostalgia; perhaps the powers that be (the media, writers, etc.) want us to learn the lessons of the past. Perhaps it is simply the universal human condition. Whatever it is, Chaucer is an excellent place to start. In essence, Chaucer is and will remain popular because his work is universal. Nationality, gender, age and centuries are all transcended in his work.

|

|

The Riverside Chaucer is full of useful and informative material about the writer. |

For general reading I would recommend The Riverside Chaucer, published by Oxford University Press, a standard university text but easily accessible to the lay reader and full of useful and informative material. However if you feel that Middle English might be a bit of a struggle there are a variety of excellent modern English versions, of which my preferred one is Neville Coghill's Penguin translation. You can also study the original text online and find out more information at this highly informative site.