| Agony Column Home | |

An

American Feast: Giving Thanks for Hillbilly Killers

The Agony Column for November 25, 2003

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

| Do not place mouse over image. |

I'm forced to admit that I didn't experience this illumination while reading Flannery O'Connor's 'A Good Man is Hard to Find'. Nor did I manage to see the obvious while enjoying Charles Willeford's 'Deliver Me From Dallas'. William Gay's 'The Paperhanger' from his collection 'i hate to see that evening sun go down' is a perfect piece of the puzzle, a notch at the highest of the high end of contemporary literature, but I enjoyed it alone. Years ago, reading James Dickey's lyrical 'Deliverance' and seeing the grueling film adaptation, I never saw the similarities.

No, not me. I made the connection a couple of weeks ago while watching, for the first time, 'The Texas Chainsaw Massacre'.

|

|

|

The most horrible of movies. |

But the horror bloom faded. My interests shifted back towards literature, science fiction, fantasy and eventually any damn book that seemed interesting. 'The Texas Chainsaw Massacre' began to seem like it might be more interesting than I had first given it credit for. Once the shock value had worn off, it began to acquire an aura of class. But still I gave it a pass.

It wasn't until the recent re-make was released that I finally managed to get past my stockpile excuses to actually screen the movie. To a certain extent, I'm glad I waited until the movie seemed calmed and I was calmer. Though it's still sold as a movie of extremes, by comparison to the tone and subject of today's network television, 'The Texas Chainsaw Massacre' is rather mild. But Hooper's vision shines with an intensity backlit by Flannery O'Connor and Charles Willeford, presaged by James Dickey and presaging William Gay. It's an all-American mishmash, a casserole of ideas. To err is human -- to kill divine. Kill or be killed. Eat what you kill. Get off the grid and you're toast. There's a big chunk of America where free-range humans demonstrate their predatory skills. You are what you eat. American, through and through.

|

|

|

| Alas, I did not buy the hardcover version. |

|

|

|

Poet James Dickey envisioned an American terror. |

Dickey tells his tale with gorgeous prose that seduces the reader into feeling safe even as they witness the vulnerability of the characters. He puts Beauty in the service of the Beast before pulling off her mask and revealing that she is not only the slave, but the master as well. Dickey's novel gets under your skin and stays there.

|

|

|

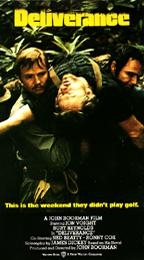

| Banjos and icons. |

Dickey wasn't the first writer to create an indelible mark with wilderness horror. The first and still the foremost writer to treat this theme is Flannery O'Connor. Her most famous story, 'A Good Man is Hard to Find' was the pioneer, the literary equivalent of those it portrayed. O'Connor's short story is iconic for all the right reasons. Talk about taut? Here's the first damn scary serial killer story hiding in your high-schooler's literature anthology. O'Connor's story is very simple, and once you twig to it, obviously the origin (purposeful or not) of the American hillbilly killers genre. In it, the prototypical suburban family heads off in the car for a three-day vacation. Mom, Dad, the kids and Gramma get in the car and head out on the highways. Before they go, Gramma's telling tales of The Misfit, an escaped killer who is headed for their destination, Florida. Once they're on the road, they stop at RED SAMMY'S BARBECUE. THE FAT BOY WITH THE HAPPY LAUGH. O'Connor has the knack to be horrifically ominous without being heavy-handed. As they pass by "Toombsboro", Gramma insists -- simply insists -- that her son, Dad, pull off the road for a little detour to see a house with a secret panel. Those all-American kids start screaming for the secret panel, and the turn is made, off the road and into American uncivilization. Another turn, Gramma's hidden cat escapes causing the car accident. From there, it's all just a roll downhill, everything so easily done, everything so easily surrendered. That helpful man they meet wants to take Dad and Mom over there a bit. While Gramma talks to the Misfit -- for that's who they've found out there in uncivilization -- the kids need to go join their parents. Gramma will join her parents as well, but not before O'Connor's white-hot writing cuts a swathe of terror and humor deep into the reader's soul. We Americans have so much to be thankful for.

|

|

|

Offstage executioner. |

|

|

|

| The Dennis McMillan edition of Willeford's novel. |

|

|

|

William Gay. |

But the peak of the American feast was 'The Texas Chainsaw Massacre', served up in 1974 with a 16 mm camera and a screenplay by Kim Henkel and Tobe Hooper. It's a plot and a voyage remarkably similar to both 'Deliverance' and 'A Good Man is Hard to Find', without the literary precedents. The movie begins with a declaration that it's based on true events (it isn't) followed by a portentous and almost humorous narration by John Laroquette. Let's get this settled right now. The story of Leatherface and family bears a slight resemblance to the story of American serial killer Ed Gein (also the basis for the movie 'Psycho'). The resemblance to Ed Gein is that Gein, like Leatherface, skinned his victims and wore their skin. Chainsaws? No. Grampa? No. Five teenagers in a van? No. So, "based on true events"? No. This was a cinematic come-on, aped by the Coen brothers with their movie 'Fargo', also "based on true events". But both harken back to the truth underlying all these American feasts; we'll believe that people off the grid will do just about anything.

The movie begins with static, news reports and washes of atonal synthesizer, snapshots of decaying corpses. Then, we're shown a full, exhumed corpse; someone is robbing the graves in a small Texas town. We're introduced to the five teenagers in a van; Sally and Franklin Hardesty, Jerry, Kirk and Pam. It doesn't take long to realize that these oh-so-civilized teenagers are potentially the most annoying and awful pampered pieces of humanity ever to litter the landscape. After a stop at the graveyard where an unhinged hick causes unease, we're on the road again. The viewers are being dragged away from civilization; only the fragile shell of the van protects those within.

|

|

|

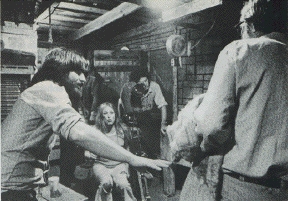

| Tobe Hooper (left) in 1974 filming the barbecue scene. |

Here in America, we can make just about any damn kind of movie we want to, no matter how heartless, no matter how horrific and unredeeming. The very existence of the movie soon becomes a source of fear. Franklin and Sally propose the group takes a detour, in the same wheedling tones as Gramma in O'Connor's journey. This leads the teens to another nearby house, drowned in the drone of a gas generator. These people are off the grid. Surrounded by a farrago of grass, weeds and wrecks, they are the rotten core of the American family.

Hooper piles on the shock and shows scenes of torture without gore. While O'Connor manufactured her terror without showing the murders, Hooper wants us to see what precisely is in all the meat we eat. He wants us to understand how it is made and what happens when you take just a little bit of America and drop it off in the middle of the American wilderness. His family feast is as pathetic as it is horrific. He also wants you to feel the same self-repulsion his survivor feels. In order to get out alive, you have to descend to their level. Otherwise, you're just the Gramma, recognizing your children, but not outliving them. They'll consume you. America is a nation of consumers.

How much of this Hooper -- and Dickey, and O'Connor and Gay and Willeford -- had in their heads before they created, and how much is an artifact of 20/20 hindsight is something that may never be determined. Readers today live in a world that was to the writers and creators of these works merely a dull piece of science fiction. We of the future can only look with horror upon the past. Our actions, of necessity, will take place in our present and our future. Almost by definition, we'll never fill the vast landscape of America. There will always be a place for the American Feast. Come up and join us. Give thanks -- you are being served. You're the main dish.