Chester Himes

Origins: From Ohio to France to Harlem

The Agony Column for August 9, 2004

Critical Essay by Norlisha Crawford, PhD

Origins: From Ohio to France to Harlem

The Agony Column for August 9, 2004

Critical Essay by Norlisha Crawford, PhD

|

|

|

|

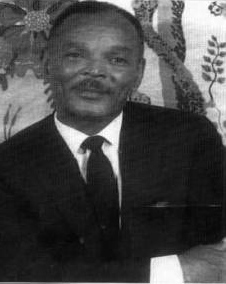

| Young Chester Himes. |

Beginning at the beginning

Understanding Himes’ ancestry is fundamental to understanding his literary work. Chester Bomar Himes was born on July 9, 1909, in Cleveland, Ohio. He was the third son of Joseph and Estelle (Bomar) Himes. Chester and his siblings, Edward and Joseph, Jr., were reared in tumultuous home environments in the mid-western and southern United States. His parents were diametrically different from each other, never having been able to find enough common ground between them to establish a loving or even respectful relationship.

|

|

|

The

first of Himes' Harlem novels.

|

Estelle hailed from a Southern middle-class—by African-American standards of the post-emancipation time—family of mixed racial heritage; her father was a small business owner, an independent building contractor. Himes, Sr.’s family was extremely poor, each member scrambling for a living as a laborer. As a young teen, Joseph was finally forced by dire economic circumstances to leave the family completely and support himself.

Although both of Chester Himes’ parents were to some extent educated, trained as teachers, Estelle Himes also saw herself as by nature an exceptionally talented poet. Joseph Himes, Sr. seemed content seeing himself as simply a qualified teacher of wheelwrighting and other mechanical skills—making and repairing farm equipment—in small African-American colleges where students learned trades for employment as agricultural and industrial workers or as themselves owners of small farms, in the tradition exemplified by educator Booker T. Washington and the Tuskegee University model.

|

|

| Himes in Paris. |

Joseph Himes, Sr., on the other hand, was afraid of whites, and so never wanted anything to do with them. He came from a family that because of extreme poverty was fractured; his father abandoned the family early in Himes, Sr.’s life, while his siblings one by one scattered to find ways to support themselves. He had been beaten down all of his young life by the violence and fear borne by Jim Crow racism at its worst. He thought sending his sons to school with Southern black children would teach his sons time-honored rules for survival under the ever-threatening circumstances of brutally segregated U.S. society.

|

|

|

Himes'

most famous novel.

|

I am not sure what Himes, Sr. saw in Estelle Bomar that made him choose her. Maybe he thought that because of her background she could help him to create the close-knit and financially secure family had he never had. Maybe he was attracted to her physical attributes. Maybe he found her keen intellect attractive. We don’t have his words or even those of others about his choice to help make any definitive conclusions. In any event, the mismatched couple married. According to Chester Himes, the couple fought constantly and bitterly from as early as he could remember. Himes’ mother seemed to hate her husband more and more for what she saw as career failures brought on by his obsequious manner and lack of drive. Himes, Sr. seemed to be hurt and angered more and more by his wife’s withering tirades and what he felt were unrealistic expectations of him, a black man in America. The three sons were caught painfully in the middle.

Chester spoke and wrote in later years of loving both parents dearly, and yet despising his mother’s arrogance, color-struck consciousness, and cruelty to his father, while also loathing his father’s lack of courage and self-pride in the face of the disparagement his mother meted out and the restrictions imposed by racist traditions and practices. In the end, the couple split after literally battling each other in a knife-wielding incident fueled by their divergent opinions on a matter concerning Chester. Edward and Joseph, Jr., had already moved from the family home; Chester was left alone to break-up the fight between his parents. The couple finally split.

Estelle moved in with Joseph, Jr., who was attending graduate school, and his wife, also named Estelle (Adams), while Joseph, Sr., moved with his teen-aged son Chester into a boardinghouse apartment. Demoralized and no longer able to find teaching positions, Joseph, Sr., supported himself and his son by taking menial jobs as they could be found. Chester Himes’ parents never reconciled nor saw each other again. The identity issues that surfaced first for him within the dynamics of his family—manhood definitions, spousal roles, the costs and consequences of inter- and intra-racial strife, the ways of socio-economic stratification, the complicated nature of love and hate, the vagaries and affects of historical circumstance, among others—are all reflected in the body of literary works Chester Himes would create.

The Harlem “domestic” series

|

|

| "Get an idea. Start with action." |

"Get an idea. Start with action, somebody does something—a man reaches out a hand and opens a door, light shines in his eyes, a body lies on the floor, he turns, looks up and down the hall…Always action in detail. Make pictures. Like motion pictures. Always the scenes are visible. No stream of consciousness at all. We don’t give a damn who is thinking what—only what they are doing. Always doing something. From one scene to another. Don’t worry about it making sense. That’s for the end. Give me 220 typed pages."

Broke and desperate for funds, Himes reluctantly took Duhamel’s challenge. Ultimately he wrote a series of nine hard-boiled detective novels. He referred to them as his “domestic” novels because he says he “put the slang, the daily routine, and complex human relationships of Harlem into [the] detective novels…This is a world of pimps and prostitutes who don’t worry about racism, injustice, or social equality. They’re just concerned with survival.” And yet, Himes also makes it clear that while the Rabelaisian upside down world of his fiction may suggest a real world community—Harlem, NYC or any urban area in the USA—it is in fact a setting that he created to highlight deliberately the absurdist consequences for one community because the nation’s social fabric is permeated by racism. Although he couched his central theme in laugh out loud humor, Himes’ Harlem novels suggest the tragic reality of a great creative potential squandered in U.S. society because ideologies and discourse of race have prevailed, along with racism and racist traditions. Combined, they have weakened if not ruined the prospects for people of color, in particular African Americans, to truly participate on equal footing with those Americans who had been allowed to enter the national mainstream by way of equal employment opportunities.

All of the Harlem series novels have complicated publication histories, involving translations or publishers’ squabbles over rights and payment terms of Himes, as well as republication under varying names, depending upon where in the world the publisher was located. What follows is a listing of the novels’ titles in English and their original dates of publication, with some notation where necessary to distinguish between British and US publications:

|

|

|

The

real cool novel.

|

The Real Cool Killers (1959)

The Crazy Kill (1959)

The Big Gold Dream (1960)

All Shot Up (1960)

The Heat’s On (1961)

Cotton Comes to Harlem (1965)

Blind Man with a Pistol (1969); the only one completed by Himes and published first in the U.S.)

Plan B (1993); at the request of Lesley Himes, the manuscript for the last novel in the series was completed by two scholars, Michel Fabre and Robert Skinner, using a number of story fragments left by Chester Himes upon his death. The novel was published posthumously in the U.S.

Run, Man, Run (1966); a stand-lone mystery novel.

A selected bibliography

|

|

| Discover Chester Himes yourself. |

I also offer here a select listing for gaining further information on Himes and his body of literature. A few simple website searches of Himes’ name or titles will reveal much more.

To find a comprehensive (although because of its publication date, now incomplete) listing of works by and about Himes, look for Chester Himes: An Annotated Primary and Secondary Bibliography, compiled by Michel Fabre, Robert E. Skinner, and Lester Sullivan, published in 1992 by Greenwood Press.

For Himes’ own words about his life and works, see Conversations with Chester Himes, published in 1995 by the University of Mississippi Press, and his two autobiographies, The Quality of Hurt (1972) and My Life of Absurdity (1976), both published by Doubleday.

For more information regarding Himes life in biography, see: Chester Himes: A Life, by James Sallis, published first in Great Britain by Walker Press, in 2000; The Several Lives of Chester Himes (1997), written by Edward Margolies and Michel Fabre, published by the University of Mississippi Press; and Chester Himes: Author and Civil Rights Pioneer (1988), by M.L. Wilson, published by Melrose Square Publishing Co.

For critical assessments of the Harlem series, see 2 Guns from Harlem: The Detective Fiction of Chester Himes (1989), written by Robert Skinner and published by Bowling Green University Popular Press, and The Blues Detective: A Study of African American Detective Fiction (1996), written by Stephen F. Soitos, published by the University of Massachusetts Press.