e've been through

quite a bit together readers, have we not? Space Opera has strutted

its stuff across this stage, and fantasy has fought final battles

for a variety of objects -- swords, spells [1],

damsels and domains. Mysteries have unfurled and been solved (pronounced

solv-éd,

not solv'd). Horrors have been unleashed and then put to rest, or

not. Literary dramas have played out with significance to last the

ages. The very Arts themselves have cried forth of wonders,

terrors, and authors who release too few novels for the comfort of

their dear,

dear Readers.

|

|

Nothing

to see here. Move along, move along.

|

Here we are, in the midst of the High Future, having left the iconic

dates of 1984 and 2001 behind. We've walked upon the moon and found

it dull enough to the tastes of our governments -- bent on conquest

and capital -- that we've not returned. Satellites circle the earth

so that our children can send text messages to one another in classrooms

that were old when the first satellite was launched, bringing forth

a reign of terror. If they could put a satellite in the sky, we told

ourselves, then surely they could drop a nuclear bomb amidst our

busy cities. We're still afraid of nuclear devices, but not those

dropped from space. Why bother, when you can pack one in a suitcase?

Our fears have evolved, but the objects of those fears remain the

same.

In order to soothe our troubled minds in this unexpected High Future,

we seek the solace of literature, fine writing that engages the mind

in a fashion that has not changed since the invention of written

literature itself. Having been through every troubled trope in the

Dictionary, having invented new words and phrases to fill that dictionary,

we're now seeking that sweet forgetfulness in the words and forms

of ages long past.

|

|

| A

classic novel about Victorian times that is nonetheless

not "New Victoriana". |

When I speak

of "New Victoriana", I want to be perfectly

clear. I'm not simply speaking of those novels that treat the Victorian

ages as their subject. Novels of this type have been around since

the Victorian age. One should perforce mention Tim Powers 'The Anubis

Gates', 'The Stress of Her Regard' and 'On Stranger Tides' as three

high-points. William Gibson and Bruce Sterling collaborated on the "steampunk" genre-defining

novel 'The Difference Engine', set in a Victorian London of steam-powered

computers. Caleb Carr's 'The

Alienist' and 'The

Angel of Darkness'

were compelling serial killer stories set in a beautifully detailed

post-Victorian New York. Yes, each of these novels were compelling

stories that created the foetid atmosphere of Victoriana. But even

if the narrators -- some of them first-person -- were inhabitants

of the Victorian ages, none of the novels were written in the precise

cadences of Victorian-era fiction. These novels were about Victorian

times, but they themselves were not New Victoriana.

For the purposes of this discourse, novels of the "New Victoriana" will

be defined as those titles I point to. Well, that, and of course

a general stipulation that novels in the "New Victorian" mode

would be those that use the Victorian style of storytelling. If I've

missed something obvious, please write to tell me, but be assured

that it's included as well. One need not have all the tell-tale signs

to get in the doors of the club. But the novels that do stand out

from their brethren. They flaunt their slightly intrusive omniscient

narrators. Their language trends towards affect. In fact, "trends" is

perhaps too light a word. Their language is heavily affected, with

curious and often arbitrary-seeming spelling. And yet, while the

diction strays towards the antiquarian, it does not quite match

the challenging nature of actual Victorian prose. It offers the

semblance

of Victorian prose, but not the substance.

Chapter titles are a plus. Footnotes will practically guarantee you

a passing grade. Labyrinthine plots, huge casts of characters, often

listed either before or after the novel itself are features that

lend themselves to New Victoriana. A novel written in this mode will

often feature the weird -- but not always. Remember that the Grand

Master of Victorian Literature, one Charles Dickens, himself was

a supernatural novelist. Indeed, his most famous work, one that has

been revised into utter unrecognizability, that is, 'A Christmas

Carol', is no less than a ghost story. It features, in fact no less

than three ghosts. One feature of Mr. Dickens' work that New Victoriana

loves to resurrect is his peculiar naming convention. These days,

it is not only in a Dickens novel that one might encounter a Mr.

Feebletoss, or a Missus Rumblebutter. Such creatures have been given

life once again, their authors having lashed themselves to a steel

pole in the moors in the midst of a literary lightning-storm. My

readers will know that I'm fond of illustrated books. But New Victoriana

requires illustrations of a certain kind, if you know what I mean

and I think you do. And if not illustrations then maps are always

welcome.

|

|

"Let us imagine then, how Law might have waited upon Equity."

|

Let us then, get on along with our discourse and actually name a

title or two in this heretofore-mysterious oeuvre. New Victorians

like to reach back into the past -- but not too far into the past.

I'm going to take a hint and go back only to 1989, when I encountered

what to me is the Grandfather of New-Victoriana, Charles Palliser's

wonderful tome 'The Quincunx'. Weighing in at a hefty 788 pages,

'The Quincunx' was Mr. Palliser's first novel, and it took him a

mere twelve years to research and write. Fix that number in our minds

readers; we're going to make use of it later in this essay. In the

interim, know that 'The Quincunx' is the modern model of New Victoriana.

If you seek the gentle pleasures of intrusive narrative, they are

here. Witness this opening passage:

"It must have been late autumn of that year, and probably it was towards

dusk for the sake of being less conspicuous. And yet a meeting

between two professional gentlemen representing the chief branches of law

should surely not need to be concealed.

Let us imagine then, how Law might have waited upon Equity."

Thus

begins the epic tale of a young man cheated of his inheritance,

forced into penury, launched into an adventure that will take

him across all strata of London's society. Readers can see the

affect,

and note the ways I which the author has made that affect enjoyable

to read and experience. The change in the reading experience

by virtue

of the mannered style of the prose is one of the primary pleasures

of New Victoriana. For years, readers have been told that transparency

is the key to great reading and writing. Writers have studiously

written themselves completely out of their own narratives. The

language is almost seen as an impediment.

But in New Victoriana, the comforting sensation of a storyteller

not too far from the reader, a presence that wants to be known

but not in the way is ever there. Palliser and all the authors

in this

mode play with the device, some suggesting that the reader will

eventually meet the storyteller, others carefully hiding the

narrator behind

a partition from whence he shall never emerge. And be assured

readers that narrator is a "he" no matter what the sex of the

author may be.

But I was referring to the delights of Mr Palliser's work, and

they are many. Mr Palliser meticulously creates the labyrinthine

feel

of the Victorian novel, with so many characters and families

that the reader needs a scorecard. And like any good New Victorian

novelist,

Mr Palliser provides several scorecards. After the narrative

pages, you will find a family tree that includes not only characters

who

are in the novel, but many who are not in the novel. You will

find a curious sigil that symbolizes the relationships between

four

families. You will find an "Alphabetical List of Names" nearly

four full pages long. And readers, you shall consult those family

trees

and that list of names numerous times. While I never thought of

it when I was actually reading the novel, should I read it again,

I

might make a photographic copy of these lists so that I could refer

to them while I was reading without flipping to the back.

And would I read it again? Why, yes I would. For the novel is

immersive and involving in the best of senses. When you are reading

this

novel, you can count on the world of the novel replacing the

tawdry world

you will find yourself in once you close the covers. The language

is so rich as to almost induce a drunken stupor, an intoxicating

delight, without any of the deleterious effects that over-consumption

of liquor bring about. Recalling all the mention of families

and family trees, this novel makes a powerful statement about

the very

nature of families, that statement being, in the parlance of

the current day, "Families are really, really complicated. And Dangerous." And

in making that statement over the length of 788 pages, the novel

backs up its thesis with every word. Mr Palliser himself is a delightful

narrator, one whom the reader can count upon to provide a wonderful

time. Yes, 'The Quincunx' will do quite well as the "Patient

Zero" of New Victoriana.

|

|

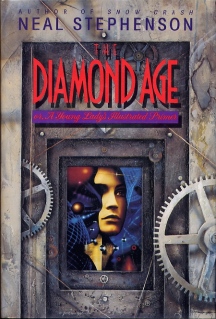

| ...or,

A Young Lady's Illustrated Primer. |

Hopping along

the time line, the world of New Victoriana remains quiet until

the year of our Lord 1995. Then, an enterprising

Young Man in the world of scientifiction, or as it is known

now "science

fiction" managed to have a most peculiar novel published. Using

the tropes of his genre, young Neal Stephenson decided that he would

declare the mid-21st century as 'The Diamond Age'. In this tome,

he tells the story of one young Nell, a member of the "thetes",

the dirt-poor urchins of Mr Stephenson's future. Through a

positively Victorian series of circumstances, she comes upon

a machine that

is called A Young Lady's Illustrated Primer. From this she

learns all manner of knowledge normally forbidden to one of

such low birth.

And with this knowledge she will encounter a destiny unfurled

in a curious admixture of New Victorian devices and rather

jarringly

21st century prose.

Yes readers, having made a rule or two, I've rather broken them

almost immediately. But after all, isn't that what they're for?

For slotting

'The Diamond Age' into this deluge of New Victoriana is something

of a stretch to be sure. But it is nothing if not an informative

stretch. And yes, Stephenson does mitigate his prose with very

Victorian Chapter separations and headings, all the while keeping

his atmosphere

quite New Victorian as well. And yet, not only is novel about

a Primer. The novel itself is a primer.

That's because -- jumping ahead, and breaking another rule,

damn me to regions infernal -- Stephenson would once again

return

to the convoluted world of New Victoriana with his latest set

of novels,

three enormous tomes any one of which might choke a dray-horse,

but

all three of which might break either the horse's back or the

reader's brain -- were it not so enchantingly written. Mr Stephenson

wrote

an entertaining novel of the present, 'Cryptonomicon', released

in 1999. He then disappeared from the "New Fiction" shelves

until last year, four forgivably long years given that the result

is The Baroque Cycle. The three novels that comprise this enormous

and complex tapestry -- 'Quicksilver', 'The Confusion' and the forthcoming

'The System of the World' (HarperCollins, October 1, 2004, $27.95)

-- offer no less than the story of civilization itself, of technology,

of the world as we know it. That story is perforce a complex conspiracy,

an arcane archaeology, through which we find meet personages both

historical and invented.

|

|

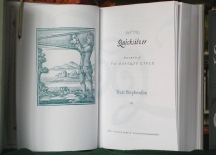

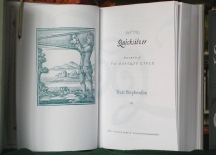

| The

very Baroque limited edition of Quicksilver. |

Stephenson's

brilliant mind has done nothing less than re-invent The World As

We Know It in a series of novels

that, while they eschew many of the principles of Victorian

storytelling -- the intrusive narrator, the antiquarian spellings,

the chapter

titles the author himself made use of in 'The Diamond Age'

-- firmly assert a Victorian style of historical romance so detailed

one feels

the need, the desire to re-read it even as one reads it the

first time. And this desire to re-read is not born out of an inability

to understand, but rather a desire to experience at a greater

depth

the pleasures provided by an author of positively astonishing

talent. What's more, a smallish publisher that goes by the moniker "Hill

House" have undertaken to publish lavishly

baroque versions [2] of each volume of the Baroque

Trilogy. Not only do you have the impetus to re-read in the

text, these versions of the novel

give

you a real,

physical nature to undertake a re-reading. The beauty of the

books is such that you will no doubt want to confine yourself

to your

parlour and use your reading gloves. It is presumed, of course

that you have

both a parlour and reading gloves. If not, please take the

opportunity to obtain them. A glance at their home page informs

me that 'The Confusion' is now available in a limited edition.

|

|

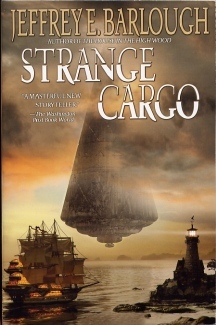

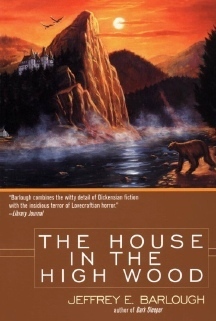

| An

unfortunate cover for Mr.Barlough's fine first novel. |

Readers are having

their patience tried, I'm sure, eager to get to what they might perceive

of as the "main course",

that is the forthcoming novel that even as I write is being

boxed and

shipped in quantities not seen since a certain to this reader

odious title squatted at the top of the bestseller list. But

first it

is incumbent upon me to mention work as fine as any work mentioned

in this article, that of an antiquarian iconoclast named Mr.

Jeffrey Barlough. I must say that I can hardly believe that

it is only

four

years since Mr Barlough's first novel, 'Dark Sleeper' was released.

Since then, we've seen only two others; 'The

House in the High Wood' and this summer's 'Strange Cargo'. Readers, let me assure

that Mr.

Barlough's work deserves to be read by every one of you immediately.

It is of the highest caliber, and moreover, utterly and perfectly

in the New Victorian tradition. Few have used this tradition

as effectively as Mr Barlough, and none have displayed the

vivid and

unexpected

imagination displayed by Mr. Barlough in these novels.

|

|

A terrorizing but subtle novel told in a faultlessly Victorian prose style.

|

The three books

comprise a sort of rough series in that they are all set in the same

place. Since they are uniformly excellent,

I'd recommend reading them in order. Moreover, the first two

are

available

at a remarkable discount. In correspondence with one of my

readers, who shall henceforth be known as Mr. Rowerbazzle,

I was told

that "the

indispensable bookcloseouts.com currently

has his first two books on sale for three and two dollars respectively." I

implore you make use of this information and immediately. The Western

Lights[3] series is set in a world that is so uniquely

conceived that readers

will find themselves propping their jaws up regularly as they

read. The city of Salthead and environs are fog-shrouded and

age-haunted.

Imagine the streets of Victorian London transported to the

San Francisco

Bay. The hills are populated by mastodons and sabre-toothed

tigers. The mastodons are used as work-creatures, to haul wagons

between

the more distant points on this landscape. Clues within the

narrative entertainingly suggest a world torn asunder at some

point in the

distant past by a meteor or comet strike. But what's left is

a pocket of Victorian-era civilization in a world where the

boundaries

between

reality and the surreally supernatural are far too porous.

|

|

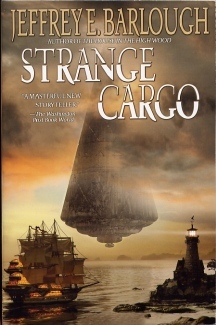

| A far nicer cover illustration graces this fine novel. |

'Dark Sleeper'

introduces Barlough's world and unto that world it introduces a

supernatural menace that is terrifying and

imaginative without any of the unpleasant violence or grue

that often mars

the

so-called horror of today. But what 'Dark Sleeper' most importantly

introduces is a unique fictional voice. Barlough makes use

of every New Victoriana technique he can lay his hands on,

and where

none

exist, he's able to invent them. The author is something

of an antiquarian himself. He's not "on the Internet" and he confines himself

to old-fashioned "mail', that delivered by humans instead

of electrons. He edits journals of authentic antiquarian

literature. He is not simply a denizen of our age who is

interested in

the aged

work of yesterday. He lives and breathes this work and it

shows in every enjoyable sentence he writes. His novels are

textbooks

of the

New Victoriana. He offers character lists, chapter titles

and characters named Mr. Nicholas Crabshawe, Mr. Ham Pickering

and professor Titus

Vespanius Tiggs. His narratives slowly and reassuringly crank

up the weird, but his demons and deities are not coil-driven

felines.

They are fully fleshed yet fleshless creatures that enable

Barlough to create incomparable chills amidst considerable

charms. Few readers

will forget the conclusion of 'The House in the High Wood'.

I require a spot of warmth even on a bright sunny day simply

recalling it.

His newest novel, 'Strange Cargo' (Ace/Penguin Putnam, August

3, 2004, $14.95) finds one aptly named Frederick Cargo setting

sail

in search of an inheritance. One can guess that this will

not

be the boon Mr. Cargo hopes it to be.

What Barlough does best, however, and perhaps better than any

other writer today, is to make use of the New Victoriana prose-style.

His

narrators are ever present and often, eventually introduce themselves.

Their identity may offer a key to the story being told. But in

any event, the voice is so delightful, the tales are so imaginative,

that one simply cannot ask for a more entertaining or rewarding

reading

experience. And by virtue of Barlough's high style, one is forced

to thank the New Victoriana school of literature for the pleasure

one is afforded when reading these fine books.

|

|

A lavishly detailed and complex supernatural soap opera in perfect New Victoriana style.

|

All of which

brings me to the latest and certainly one of the most notable

additions to this fine school of literature.

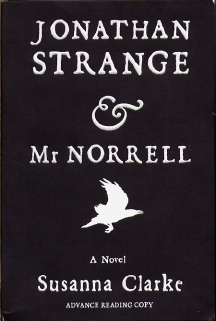

'Jonathan

Strange and Mr Norrell' by Susanna Clarke (Bloomsbury,

September 8, 2004,[6]

$28.95) offers nearly the full spectrum of New Victoriana

flourishes in a compact 800 page book-brick. Readers are

now adjured to

recall

my earlier mention of Mr. Palliser's epic twelve-year struggle

to write and research 'The Quincunx', his first novel.

Ms. Clarke underwent

a similar battle to finish her novel, but in my humble

estimation it was worth the wait -- though I certainly hope we

won’t have

to wait so long for another! I must confess that I entertained

strong feelings of doubt as to the worthiness of this novel.

The only term

that is properly applicable is that ungainly word "hype",

short for hyperbole. The hyperbole associated with Ms Clarke's

novel made me severely uncomfortable. I was both doubtful

and fearful that

it would live up to the praise bestowed upon it. The first

words I heard were from a well-known bookseller who repeated

the since

oft-used phrase "the adult [mumbly-mumble]".

I'm not certain who coined that phrase. Certainly it was

someone

with commerce

in

their eyes and little in their brains. Whatever it might

be, 'Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell' is certainly not

that. I've

not completed

reading the novel, so I'm offering not a review but rather,

a progress report.

As 'Jonathan

Strange and Mr Norrell' begins, it is 1806 in England and the titular

Mr Norrell manages to trick

the York

Society

of Magicians into turning over all their texts on theoretical

magic.

As the narrative

unfolds, it becomes clear that this is not exactly the

England with which we are familiar. Nor is the form of

storytelling

with which

we are exactly familiar, for Susanna Clarke shows from

page one a determination to re-invent the Victorian tome

for so-called "modern" readers.

We are offered a novel with chapter titles and lovely,

understated illustrations by Portia Rosenberg. One can

quite comfortably

imagine the illustrations accompanying a serial version

of the novel run

in 'The Strand' magazine, be it the original of the Victorian

age or the current revival, done in equally fine style.

I rather wish

that Ms Clarke had seen fit to include endpaper maps for

the unschooled-in-English geography American audience of

whom I

am a member. And I confess

to some small surprise at the lack of a list of the dramatis

personae. But neither of these is an issue once one plunges

into the narrative.

There, the reader will find a comfort unlike any available

in the average modern novel. For all the size of the novel,

the cast of

characters is fairly short and easily remembered. The prose

retains the mannered aspects of the best new Victorian

fiction, but reads

without effort. In fact, as I mentioned above, there's

a comfort and a confidence here that makes the reading

experience

particularly

enjoyable. It's also much easier to read than one might

expect. The pages melt away without effort.

For those who were actually hoping for an "adult &tc &ct",

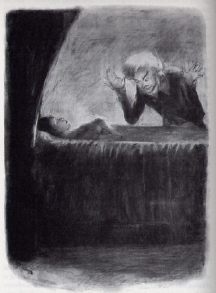

prepare to be disappointed. The titular Mr Norrell is a very disagreeable

sort, churlish, selfish and highly insecure. Once he decides to re-invigorate

the "English tradition of magic", he moves to London, where

he falls under the sway of two rather disreputable hangers-on, Mr

Drawlight and Mr Lascelles. They convince him that he needs a powerful

act of magic to start his career, advice he unwisely follows. For

to do so, he's forced to ask the assistance of one of the residents

of the world of Faerie, a certain "thistle-haired man",

so-called because of the mass of whitish hair atop his

head. This proves to be an unfortunate decision. It is,

in fact,

the beginning

of an invasion.

Jonathan Strange does not show up until well in the narrative.

He's a dissolute gentlemen looking for an occupation to interest

him,

and he hits upon magic. He proves to be rather good at it, and

eventually manages to become the pupil of the reticent Mr Norrell.

The two have

quite different styles, and eventually they clash. But neither

of them is the enemy.

|

|

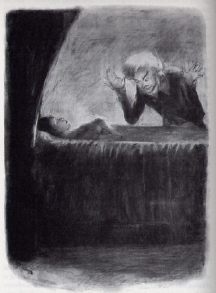

| "At

the sight of Miss Wintertowne the gentleman with the thistle-down

hair suddenly became very excited." An illustration by

Portia Rosenberg. |

While the veritable reams of press would have this novel as a

sort-of battle of dueling magicians, I would describe it as an

alternate

history in which England has a nearly-lost technology of magic

that must be brought to bear again to repel an invasion from

a supernatural

reality. Clarke's faeries and the world they inhabit are the

real stars here. Yes, Ms Clarke has performed an amazing scholarly

feat.

She's certainly created a remarkably detailed alternate history

of England, one in which an organized and detailed system of

magic once

ruled. She extends the reach of her New Victoriana by inserting

scholarly and very Victorian footnotes throughout the text. Some

of these footnotes

might be publishable as stand-alone short stories. Her system

of magic really does seem like a system, with a complex history

of success,

failure and documentation. One can imagine shelves of notebooks

crammed with faux histories. Better still, one can imagine the

histories

themselves, since many are detailed in the footnotes and the

narratives.

But as I said, the real stars here are Clarke's sinister faeries.

She imbues them with the perfect balance of menace, malice and

malevolence. Better still, the humans that surround them are

utterly clueless

as the nature or even existence of their enemies. The influence

of the faeries makes itself felt in enchantingly surreal moments,

when

characters suspect they may be slipping into a dream state. For

readers who like sly and intelligent antagonists who have both

great power

and great limitations, for readers who like understated menace,

Clarke provides a cornucopia of literally enchanting reading.

While the prose does have the general feel and appearance

of the best of New Victoriana, Clarke manages to somehow

make

it all read

quite easily. There's a rather compulsive feel as one reads

the novel, though the action is carried out over so many

pages and

in such detail

that it can't properly be called a "page-turner" most

importantly because lending it that appellation might suggest

that the novel

is vapid, and it most assuredly is not vapid. It's not

profoundly meaningful either, and that's all for the best.

'Jonathan

Strange and Mr Norrell' reads like dream, footnotes and

all. For those

who like to become lost within the pages of a very long

book, this is

an excellent novel.

Readers must take my word with an important precaution. The story

is, in theory, building up to a nice climax. However, I'm about

220 pages from the final words. I don't think that it's possible

that

the novel could be this confidently written and end up nowhere,

but stranger things have happened. But thus far -- and this is

in fact

only a progress report, not a final review -- 'Jonathan Strange

and Mr Norrell' is standing up as a fine piece of fiction and

a sterling

example of New Victoriana.

Readers who are interested in obtaining this tome will have to

wait until September 8 to get the hardcover version being

released in

America and September 20 to get the hardcover version being

released in the UK. I know of more than a few readers who will

demand

both. Ms Clarke is about to launch a tour of the American

territories[4] that

will enable readers to obtain her signature on the the

first editions being shipped even as I write this. Should circumstances

prove this

to be the enormous success that the publishers are anticipating,

those first editions will be worth quite a bit more than

their

cover price. In addition, much has been made in the News section of this

venerated E-zine about the limited edition,[5] which I

suspect my readers managed to buy out almost single-handedly.

What this

adds up to is

a bevy of books that readers will be loathe to take to

the tacqueria

to read during lunch. A reader who wrote me --let us call

her MAD -- suggested that those of us who would like

to preserve our editions

may obtain the trade paperback from Canada. In her wisdom,

she

suggested we search via a certain unnamed Canadian vendor

via this key: 0747574111.

I will leave it to the more diligent readers here to determine

what use to make of this information. I merely suggest

that having more

than one copy of this book will prevent at least one copy

from being stained with hurled-about foodstuffs.

|

|

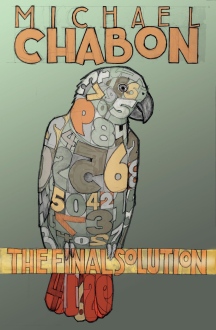

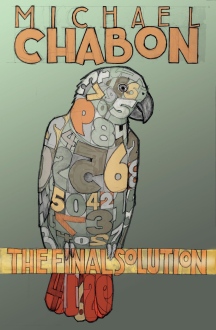

Your first look anywhere at the cover of Michael Chabon's latest novel, a fine example, I suspect, of new Victoriana.

|

No less a literary giant than Michael Chabon will soon be

offering his own contribution the New Victoriana oeuvre,

the compact and

intriguingly titled 'The

Final Solution: A Novel of Detection'.

Originally published

in the Paris Review, where it won a prize, this novella (at

least in it's original incarnation) offers up a new adventure

for the

un-killable Sherlock Holmes that includes just a dash of

the fantastic. Chabon

is certainly one of our most distinguished literary authors

and seems bound and determined to offer a contribution to

the world

of genre

fiction as well. On his website, he describes this book thusly:

"My novella, "The

Final Solution," which

first appeared last year in The Paris Review, will be published

on December

1 by Fourth Estate (HarperCollins). This will be a special,

small-format hardcover, with a stunning cover and six interior

illustrations

by

Jay Ryan."

Chabon is

a man endeared of the throwback. He forcibly mutated a respectable

literary quarterly, 'McSweeney's

Quarterly

Concern' into

'McSweeney's Mammoth Treasury of Thrilling Tales', sending

shockwaves of abreaction throughout the genre fiction

establishments. The

resulting editorial hemming and hawing was provided an

enjoyable spectacle.

He averred the power of "plotted fiction". He's

demonstrated throughout his career his ability to give

genre fiction a literary

infusion that actually makes the final result a better

reading experience. I'm confident his experiment in New

Victoriana

will be -- in fact,

already was -- successful. Having missed the Paris Review

Summer 2003 Issue, I'll eagerly await this ornamented hardcover

version.

In the interim, I will continue my journey towards the

end of the tale of 'Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell',

wringing every

bit of

enjoyment I can from every word the author has written.

From this smattering of books both old and new, it's

clear that New

Victoriana

will continue to thrive, and indeed, become widely known

and respected throughout the literary landscape. One

hopes that those

who enjoy

the obvious and easy-to-find works will take the trouble

to seek out their lesser-known counterparts. I shall

await that curious

future, which shall, at least in literary terms, resemble

more and more the

past from whence it emerged.

|