Prizing the Derivatives

The Perfected Pastiche

The Agony Column for March 18, 2005

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

The Perfected Pastiche

The Agony Column for March 18, 2005

Commentary by Rick Kleffel

But as bookselling and publishing became profitable, the need to differentiate between types of books arose. And thus, genre fiction as we know it today was created -- not by writers, but by the marketing departments and booksellers. By subdividing the realm of fiction into easily identified genres, booksellers made it easier for fans of certain types of fiction to find what they were looking for. Here in the 21st century, it's easy to think that writing has always worked this way. But this weed has really only overrun the lawn in the last fifty or so years. Within genres, certain writers seemed to single-handedly create -- or discover -- iconic subjects, or what I'll call tropes. There's no doubt that Arthur Conan Doyle quite specifically created Sherlock Holmes, a Victorian detective. And it's not disputed that Jack Vance created the Dying Earth, our world, millions of years in the future, in a time when science has become practically indistinguishable to the reader from sorcery. Robert A. Heinlein was the first writer to describe what he called "Power Armor", a spacesuit that acts as a space ship, allowing an individual human to be launched from an orbiting ship and sent into a battle on the planet below. H. P. Lovecraft indisputably created the being we all know as Cthulhu. And Jorge Luis Borgés created 'The Universal History of Infamy', a fictional non-history of figures real and unreal.

Lesser. Of course, in the world of literature, tropes were created hundreds of years ago, and when new generations of writers took them to hand, they were not dismissed as lesser. The romance novel. The novel of self-discovery. Nobody dismisses out of hand what Michael Chabon calls a "contemporary, quotidian, plotless, moment-of-truth revelatory" story simply because they've been done quite well in the past. Each one is evaluated on its own merits. Dismissing writers who used tropes that had been created by others would result in dismissing much of the great literature of the twentieth century. And though the genres are still quite young, it would be quite unwise to dismiss the literary value of writers working in pastiche and derivative fiction.

Those notions, deeply ingrained, told me that great writing, great art always had to be one-hundred percent original. Every thought, every phrase, every concept had to be fresh, newly minted by the inspired vision of an artiste. Any tinge of derivation, of un-originality could only dilute the experience of a written work. The true greats were not allowed to stand on the shoulders of giants, nor were they allowed to appropriate the characters, the ideas or the settings of the giants. Building from the ground up was required. If it was good enough for the giants, it was good enough for today's and tomorrow's writers as well. But all it takes is a couple, well three, great novels to overturn that idea. Standing on the shoulders of Arthur Conan Doyle, Michael Chabon's Holmes pastiche, 'The Final Solution', is powerful enough to make the most ardent Holmes fan tear up in joy, while Laurie R. King's 'The Game' is her latest excellent Holmes-with-a-wife mystery.

But the 20-20 clarity of hindsight still rules our view today. Tor releases 'Black Brillion', and it gets some notice, but it is, after all, working territory first trod by Jack Vance. Hughes acknowledges this with a nod to the Jack Vance BBS at the beginning of his novel. Tor also let slip the dogs of an 'Old Man's War' by John Scalzi with no more warning or marketing than they might accord to a Yet Another Young Adult novel. Scalzi likewise thanks Heinlein both at beginning and end, and well he should. But Heinlein himself should be thankful that his legacy is handled with a skill equal to his own. In the firefly life of Night Shade's Ministry of Whimsy Imprint, under the careful guidance of Jeff VanderMeer, we first saw the flapping wings of Rhys Hughes Borgesian tribute, 'A New Universal History of Infamy', an amazingly worthwhile and faithful sequel to the original work, 'A Universal History of Infamy'.

"Of such great powers or beings there may be conceivably a survival... a survival of a hugely remote period when... consciousness was manifested, perhaps, in shapes and forms long since withdrawn before the tide of advancing humanity... forms of which poetry and legend alone have caught a flying memory and called them gods, monsters, mythical beings of all sorts and kinds..." A veritable army of writers manage to cleverly combine Lovecraft and Doyle in 'Shadows Over Baker Street', with Neil Gaiman winning the Best Short Story Hugo Award in 2004 for his contribution to the anthology, 'A Study in Emerald'. (Of course he tried to read that story at the 2002 Torcon, but was booted from the room due to time restrictions. "Damn pastiche, begone!" they might as well have said.) Damn pastiche, begone? By any measure, the pastiche, the derivative appears to be a bastion these days of top-notch literary work. The works that started this thread of thought in my tiny brain were Tor's two recent releases, Matt Hughes' Black Brillion' and John Scalzi's 'Old Man's War'. I really enjoyed both works, and then sort of twigged to the fact they both were quite openly derivative works. 'Black Brillion', for example, begins with a dedication "To Mike Berro and all the gang on the Jack Vance bbs." His setting of Old Earth is clearly both a riff on and a tribute to Jack Vance's Dying Earth. The colorful characters and the mix of science and magic also speak directly to Jack Vance's iconic work.

Perhaps one of the most unusual pastiches or tributes to hit the bookshelves recently was Rhys Hughes' 'A New Universal History of Infamy'. (Hmmm.... There is indeed a plethora of Hughes in this article -- perhaps there's something up with that name!) Borges' original work, 'A Universal History of Infamy' was conceived as a light entertainment, but became a literary landmark in South American literature. In it Borges spins off entertaining bits of history about infamous historical figures -- all of it false. He does so in a very unique format, a format that Rhys Hughes copies precisely and with equally entertaining results in 'A New Universal History of Infamy'. The brilliance of both these books makes them entertaining, hilarious and truly mind-boggling. And as you read Rhys Hughes derivative work, you might begin to feel as if you've tumbled on a whole new genre, not just a work and a follow-up. Hughes drills through to the essential elements that make Borges' work so powerful. He taps the same source of literary energy, and the results are exemplary -- and totally derivative, in the best sense.

But King does a lot more than keep up with the Great Detective. She also keeps up with Doyle's intricate narratives and the historical background that was just everyday reality for Doyle himself. But more than that, she infuses her writing with a sense of humor that captures the wit of Holmes as the character himself might have preferred. And although she's writing about Holmes and Russell, she incorporates elements of Doyle's other series character Professor Challenger. King's novels offer readers of Doyle's work an entertaining extension of more than just the Holmes stories. One of the books that really brought out the power of derivative and pastiche fiction for this reader was Michael Chabon's 'The Final Solution'. From the get-go, Chabon's novella emphasizes one of the most interesting aspects of the pastiche, that is, the ability of this form to adapt to both the source material and the current practitioner. Chabon is one of our most highly regarded literary writers, but here he proves that one doesn't reach the rarified heights of literary stardom without down-to-earth writing chops. 'The Final Solution' is set in the midst of World War Two, in the final years of Holmes' life. Chabon hits each note perfectly; the structure of the novella, the crime itself, the evocation of Holmes and the evocation of his environment. However, his most brilliant touch is his ability to provide for the reader the same pleasures that Holmes himself experiences in solving a case, as the reader comes to realize aspects of 'The Final Solution' that Holmes will never see. Chabon manages to create purely cerebral pleasures that will authentically boggle the mind, and probably bring a tear to the eye of Holmes' most ardent supporters.

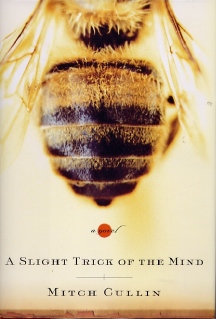

There must have been something in the air say, some what -- two, three years ago? You've got to keep the publishing lag in mind when making presumptions about the origins of novels, since what we're seeing this month was created long ago. But whatever it was, it must have been quite powerful. Otherwise, how to explain yet another super-desirable, super-literary novel featuring an aging Sherlock Holmes? In Mitch Cullin's 'A Slight Trick of the Mind', we meet Sherlock Holmes at the age of 93, shortly after the end of World War Two.

But it would take him a while to get back to the iconic character. In the interim, he's addressed adolescent angst in 'Whompyjawed', written academic satire in 'The Cosmology of Bing', collaborated with collage artist Peter I. Chang in 'UnderSurface', written a detective novel in verse titled 'Branches' and tackled Texas teenagers in 'Tideland'. 'Tideland' was recently adapted to film by Terry Gilliam, a sure indicator that this is a writer of interest to my readers, no matter what their chosen genre. With 'A Slight Trick of the Mind', we find Holmes in 1947. He's just returned from Japan, where he found not only the restorative prickly ash, but also the horrific vistas of Hiroshima. His brilliance is now threatened by a faulty memory, but this does not stop him from trying to solve a case unearthed by his housekeeper's son. Cullin brings years of Holmesian interest and a quiet, powerful prose style to this novel. In it, he undertakes the daunting task of humanizing Holmes, which is, of course, not an easy task. But he does so by unmanning him, by subtly, slowly severing Holmes from the faculties that gave him such power as a character. It's a fascinating experiment with an impeccable pedigree, and yet another reminder that derivative fiction may indeed claim the high ground. All of this culminates, of course, in 'Shadows Over Baker Street', the brilliantly conceived anthology edited by John Pelan. While not every story is of the literary quality of Neil Gaiman's prize-winning 'A Study in Emerald', every story does effectively straddle the shoulders of two giants -- no easy feat. Moreover, not once will the reader feel anything less than amazed at the concept and execution of this anthology. What should be doubly derivative seems instead twice as original. In fact, you can re-invent the wheel -- and improve upon it. So now I find myself open to whole new realms of fiction and looking at old titles with new eyes. Sure original is good, but it is not necessarily better. As ever, the ultimate worth of the book hinges on a number of factors, and a skilled writer can use any tool to create a great work of art. Even if that tool is part of another work of art. |