Being Smart

An Interview With Lou Anders

The Agony Column for April 18, 2004

Interview Conducted by Rick Kleffel

An Interview With Lou Anders

The Agony Column for April 18, 2004

Interview Conducted by Rick Kleffel

RK: Lou, how you did you get started in the writing business in the first place? Did science fiction lead you to writing or did writing lead you to science fiction? LA: I came in via media "sci-fi," which may surprise some people given a number of vehement public statements I've made and articles I've written denigrating Hollywood for their usual bastardization of the genre. When I was a child, my father shoved a copy of ERB's A Princess of Mars into my palms and ordered me to read it. And I devoured everything Burroughs then available in about two summers, and went on to read copious amounts of Moorcock and Lieber. But I left science fiction in high school for writers like John Irving (his World According to Garp was hugely influential on me) and Tom Robbins, and in college and immediately thereafter I was much more interested in 70s cinema and experimental theatre. I was heavily into Maya Deren, Antonin Artaud, Stephen Berkoff, Russ Meyer. I didn't read any science fiction to speak of, though I did make a return to comic books with Watchmen and Dark Knight. The short of it is that theatre in college lead to a partial scholarship to study acting in Oxford and London, which lead to directing plays in Chicago, which lead to working on sets in Los Angeles, which lead to journalism & screenwriting, the former being "scifi" based, which lead to internet publishing, which lead to publishing, which lead to here.

LA: Well, I didn't write for Star Trek and Babylon 5, I wrote about them. I got very lucky in that I fell in with Titan Publishing in the UK just about the time they were launching the first Star Trek magazine – previous fan-mags had been one or two interviews with Random Red Ensign number 6 followed by 20 pages of advertising. And Titan came along with the desire to do a full-on, 80-page, large format magazine that would run 30 to 40 articles an issue and use 250 color photos. Paramount had no idea how to accommodate such a license. There was no infrastructure in place to deal with it, and they needed a man on the ground to put it together. Jean-Marc Lofficier recommended me to Titan on the strength of my very first interview and they took me to breakfast. And I sat there and – I think it's safe now to say – lied through my teeth and said "You will never find, in all of Los Angeles, a better Star Trek journalist than me." At the time, I didn't watch the show, and my first and only piece of journalism – a Doctor Who convention report for Sci Fi Universe – had yet to come out. But miraculously they bought it, and pretty soon I was their "Los Angeles Liaison" churning out about 30 articles a month on average and living on the Star Trek and Babylon 5 sets. But the thing is, while what I said was a bold face lie at the time, I worked my ass off to make it true. I ended up writing about 500 articles in five years, and by the time I quit journalism in 1999, both Deep Space Nine's Executive Producer Ira Steven Behr (the last truly talented producer to work for that franchise) and Babylon 5 creator J Michael Straczynski confessed that I was their preferred journalist when it came to covering their respected shows. But I was writing film scripts with a partner on the side, two of which were optioned by production companies, but, like 99 out of 100 Hollywood projects, never got off the ground. We were also pitching regularly to Star Trek, and they liked us and our ideas and kept having us back, but then Voyager went so far downhill we realized that we didn't want to succeed with them, and we never took them up on their last pitch invitation. They'd done an episode where the main jeopardy was that Harry Kim was worried that his parents would forget him after he'd been lost in space for a couple years. I kid you not. They've found some Federation email trapped in an alien transponder device and everybody's getting a letter from home but Harry. In the last three minutes of the show, a final piece of mail that was stuck in the system finally jiggers loose (imagine that) and low and behold, he learns that his parents still love him. We were so disgusted we didn't want to go into our pitch meeting the next day. But we did, and we threw out a couple of what we thought were some pretty clever ideas, and Bryan Fuller asked us "Did you see last night's episode?" And while he told us how he thought it epitomized the best that Star Trek had to offer, and could we come up with something like that, we sat there holding our breaths afraid to look at each other for fear we'd burst out laughing, and we walked off the Paramount lot, and I looked at my partner and said, "Dude, we're not coming back. The worst thing that could happen to us as writers is that they could buy something."

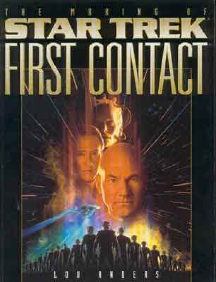

LA: I'm not a big believer in the media-tie in. I can see its value in sharpening skills, but it's not something I think is very, um, literary, and I would rather the eyeballs that are wasted on TV tie-in material were directed towards the real stuff. That being said, my friend Sean Williams has cautioned me that media tie-ins have their place, and the other day George Zebrowski, who doesn't suffer unambitious science fiction lightly, told me that what he bemoaned was not that the media tie-in existed, but that it didn't set its sights higher in terms of quality. (Furthermore, in the interest of fairness, I must confess a fondness for certain Doctor Who books.) RK: And I too, especially those by Mark Morris. How did you get the gig writing the book about the making of 'Star Trek: First Contact'? LA: Titan called me up and said, "We've just negotiated the license. Do you want to do the book?" And I said, "But the movie just wrapped two days ago, all the press junkets are over, and the actors are sick to death of talking about it." But I took the gig, and it was sheer hell. I spent a period of six weeks where I didn't talk to anyone who wasn't working for Paramount, shut in my studio apartment in Venice Beach conducting, transcribing and writing up multiple interviews a day; begging, bribing and threatening agents to get their actors to step up for one more interview; and typing until my wrists hurt so bad I had to take a month off journalism afterwards to recover. No kidding. And I could not have done it without the assistance of Kristin Torgen, my ally in the Paramount publicity department. The rest of the department couldn't give a shit about an already-licensed and paid for tie-in book, because, hey, that was written for a guaranteed core that would come no matter what crap was on screen and didn't count as a source of new "impressions" (their term for registering awareness with potential viewers). I don't know where she is or what she's doing, but the book would not exist without her and I'm grateful.

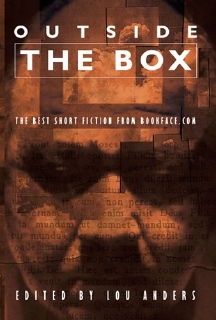

LA: From beginning to end? Surely not. Well, I was living in West Hollywood, Deep Space Nine had ended, Babylon 5's Crusade spin off had been canceled, I'd broken up with someone in a bad way, my writing partner was talking marriage with his girlfriend, and I was eking a living sourcing photos for the Xena: Warrior Princess magazine. Dark days indeed. An ex-girlfriend/old friend from college called and said she'd like to fly me to San Francisco to act as a possible media consultant for a dot com she'd founded. Highly skeptical, I come up, and they show me the demo, which was for a browser-based reading window that let you open fully searchable texts online but wouldn't let you print out or download. The concept was that it would track ad banners and allow click thrus to Amazon and B&N, so that it would either drive sales (by letting you preview) or generate revenue while you read. We pitched it to publishers as free publicity that paid them back rather than charged. I signed on to build a science fiction portal that would point to the site and that quickly grew to being their Executive Editor and overseeing content in thirteen categories, including nonfiction, religion, business, romance, mystery, history, etc… We had major cooperation from all the big guys – Penguin, Random House, Warner Books, St. Martins, etc… and logged forty-thousand plus users in a matter of months. But of course the bottom dropped out of the ad revenue model and we were killed in the crunch. But now Amazon and Google Print are starting everything up again and crossing all the same bridges we did five years ago, and Salon.com's even found a new model to make the advertising pay. Sometimes it doesn't really pay to be first to market. Too bad, so sad. But the upside was that science fiction readers and writers are notorious early adopters and so after just a year of operation I knew scores of people in the field. So when the writing appeared on the wall for Bookface, I was leveraging my contacts to—Oh look, your next question! RK: Bookface.com led to your first anthology, 'Outside the Box'. How was it for you to go from the New York publishing world you (presumably) experienced with the 'Star Trek' book to the POD environment of Wildside? LA: Well, I went from the London publishing world, actually. But at the time, I thought POD was simply another facet of the digital revolution and the new economy that would change the world, and so I was wildly and naively enthusiastic. I'm much, much more skeptical now and, in fact, wouldn't advise anyone serious about being taken seriously to go the POD route, as an author or a publisher. I'm sure that something like it, as well as something like the eBook, is going to be here one day, but it's like laser discs and DVDs. The idea is there, but the format's had to go away, and will come back in a decade when they get it right.

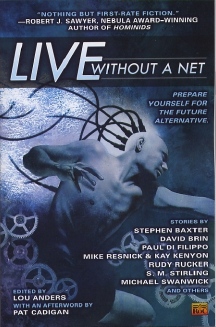

LA: Splendid. I've been very fortunate in both my editors at Roc—Jen Heddle on Live without a Net and Liz Scheier on FutureShocks. I was frankly surprised that Roc took on Live, because apart from Al Sarrantonio's Redshift, I didn't see them doing a lot like it. I had set the anthology up at a small press that was slowly going under, and the book was about half done, and in one frantic weekend at the World Fantasy Convention in Montreal, I built a house of cards by getting both some big name authors and a "major name" publisher interested by guaranteeing each the other. Someone introduced me to Jen, I asked "Do you do anthologies?" and when she said, "Sometimes," I replied, "My name's Lou Anders. Come let me buy you a drink." And again, I was very fortunate and very grateful that she liked the idea and followed up, and when she called to say they'd buy it, I put down the phone and ran laps inside my house. But Live without a Net was a bitch to do because it stretched out over a year and a half and changed publishers midway. And I'd more than half filled it with some very talented, but then largely unknown writers, and now I had to get a requisite number of "names" in without exceeding my word length, not all of whom came through, and I had to hammer and slice the thing into shape. FutureShocks, by contrast, has been an utter dream, largely due to the success of Live. Everyone signed up enthusiastically, wrote within their prescribed word limits, and handed their stories in on time. It's been so easy I feel guilty. And though I didn't have to buy Liz a drink, all my dealings with her suggest she's a marvelous person who really "gets" SF, and a great asset to the new Roc, and the first rounds on me next time we're in the same city. RK: Tell us a little bit about 'FutureShocks'. LA: FutureShocks is my anthology about new fears and cultural transitions arising from biological, sociological, technological or environmental change. Science fiction is often called the literature of estrangement and distinguished from the other genres by its refusal to make the reader too comfortable, and I wanted to explore that for its own sake. I'm quite happy with the results, which contains some truly excellent work, and I'll be anxious for it to be unleashed on the world.

LA: Well, the confession is that MonkeyBrain founders Chris Roberson and Allison Baker are dear friends, and while they wouldn't make a decision they didn't see a business upside to, they've been very good about letting me do the book I wanted to do. In their and my defense, I didn't know Chris from Adam until he handed in "O One" to Live without a Net, and I thought it was utter genius—born out by the Sidewise win and the Campbell and WFC nominations — so the nepotism really did follow sincere professional admiration and not the other way around. But Projections is a bit of an odd animal. I read a lot of SF nonfiction, a copious amount, and I was leafing through Science Fiction Studies or something similar and thinking about the fact that by and large, the SF criticisms that I enjoy the best are the pieces that are written by the writers themselves. And that I couldn't put my finger on a good book that aggregated a large chunk of same and that I personally would really like such a volume for my own shelf. When it began, it was actually two books, one on literature and one on cinema, and it was a decision on the part of MonkeyBrain to combine it to one volume. We thought about sectioning it into two parts, but it didn't break nicely either word count-wise or TOC-wise, so we just jumbled everything together, hoping that the subtitle "Science Fiction in Literature & Film" would be enough to lead folks to expect a bit of both. But, wouldn't you know, that seems to be one of the aspects reviewers are stumbling on, who seem to be wanting one or the other. I'm also very concerned with (read: "exasperated by") the dichotomy between SF literature and sci-fi film and said as much in my opening essay in what I thought was an erudite manner, but maybe I should have just written that, "Hey, by golly, I think the best writing on writing is by writers and here's some really cool pieces. Now go enjoy them in their own right." Anyway, I'm very proud of the result and would love to do a follow-up collection one day if the opportunity arose. RK: How did you get involved with Argosy? What role did you play in the conceptualization and the design? And what led to your departure? LA: Ah, Argosy. I imagine I'll have to endure questions about that for a while, and I look forward to my other work reaching the level when I can leave that behind (it's already migrating off the bio), but I suppose I'd better say what I can right now. Depending on the time of day, it's a painful subject because I'm both still very proud of the work that I did on the first three (yes, three) issues, but at the same time, I'm hyper-aware of certain shortcomings and behind-the-scenes problems that I'd rather not be associated with. The short of it is that a very charismatic man came along at the right (wrong) time with plans to craft a string of magazines, and we, who love the short fiction format so much and bemoan the dwindling state of the digests, allowed our wishful thinking to get the better of our judgment, fell in line with this pied piper and broke our backs and burned our candles low and strained our relationships and mortgaged our reputations to craft for him a thing of beauty made of gossamer and candy floss and tissue paper, and when the house of cards was found to be wanting and printers went unpaid and subscriptions unfulfilled and my own contracted-for back pay reached astronomical levels, and I had mounting "creative differences" (read: serious ethical and moral problems) with their business practices, I removed myself and asked that no mention of my name in conjunction with the magazine ever be made again. And I mourn for what might have been, but I cannot, in good conscience, countenance anything coming out of there.

RK: What did you see yourself doing after you left? How did Pyr come into being? Did you approach Prometheus? LA: Pyr was utterly and totally a godsend, if one can use such a description in reference to working for the largest atheist publisher in America. A very good friend of mine from Bookface.com saw a job listing for an acquisitions editor to work in science fiction and forwarded it to me, whereupon I ignored it out of misplaced loyalty to Argosy. My wife, however, is many orders of magnitude smarter than I am, and tricked me into applying by suggesting that we just "see what happens." What happened was that they flew me to New York and over the course of a day, it was mutually agreed that what they wanted was more of an editorial director than an acquisitions editor, and we shook on it and I flew home. RK: Prometheus has a rather skeptical slant when it comes to science publishing with authors including 'Skeptical Enquirer' author Martin Gardner, and it seems that this might cause some friction with the speculative nature of science fiction itself.

But at the same time, as I said to Prometheus when I accepted the job, I don't want this imprint to be as narrow as to confine our authors to one agenda, so that while I am selecting books that mesh broadly with their overall aesthetic, I'm not limiting us to just one mode or sub-genre or philosophical position. However, that being said, I'm very unlikely to do a ghost story, or an angel book, or a story about ancient shamans imparting long forgotten spiritual wisdom. We will publish fantasy, and soft-science SF, but I hope to ensure that we always have a solid through-line of the pure stuff. Even Chris Roberson's Here, There & Everywhere, a grand adventure novel which takes place all over time and space and dimension, is rigorous in its physics. RK: What kind of editorial dictate did Prometheus give you or were you just given free reign? LA: Prometheus has been wonderful in that they are a 35-year-old company of excellent reputation with a great deal of experience that are staffed by some highly-talented, ultra-competent, and extremely hard-working individuals who know absolutely nothing about science fiction. So while they are deferring to my judgment in a wide range of matters, from choice of material to selection of cover artists to advertising venues and even fonts and paper stocks, I am fortunate in that they have excellent art, publicity, editorial, production, sales and marketing departments and are working very hard to produce what I think, all modesty aside, are some very damn good-looking books. And they are marketing and publicizing the hell out of them. I could not be happier with Prometheus. They have really stepped up and demonstrated a commitment to this line beyond my expectations.

LA: You know, in terms of selection, the first season was relatively easy. I knew exactly what I wanted and was able to get it. Execution was another matter. I left for a pre-arranged, month-long trip to China with my wife right after accepting the job (and yes, I took a stack of manuscripts along), but I returned with only three months remaining to have the books nailed down, contracted, illustrated, launched, etc… It was a crazy, crazy time, haggling with agents and drawing up contracts while writing catalog and jacket copy and approving artwork and layouts and everything all at once—a year's worth of work or more compressed into a very narrow window, and I honestly don't think I've worked this hard at anything since I was living in the 14-hour workdays of the dot com industry in 2000. It's slowed down a little bit sense then, but then again, here I am at 11:21 PM working on this interview, so by slowed down I mean to the normal craziness. In terms of the nature of the picks themselves, it's a very calculated list. Our first season is comprised of four original novels, two North American debuts, one classic reprint, and one anthology. Each of our seven novelists (and, of course, our anthologist Gardner Dozois) has been distinguished, either with major awards or multiple nominations. The books are weighted towards hard SF, but contain two fantasies (one secondary world, one historical), one sci-fantasy or soft SF, and an anthology of stories examining the very Promethean struggle of science vs. superstition. And yes, it's highly reflective of my "editorial intentions." RK: Your catalogue includes some heavy hitters from the UK that to my mind have been conspicuously and mysteriously absent from the US scene. Tell us why talented writers published by major houses in the UK don't automatically get picked up by major houses in the US. LA: John Meaney. John Meaney. John Meaney. I will say—and can say with integrity since I've been saying it since 2001 when I'd never heard of Prometheus or Pyr—that John Meaney is the best hard science/space opera fiction writer in the field today. Possibly equaled, but not exceeded by, Charles Stross. I have been lambasting US publishers to pick him up since I first read Paradox, never dreaming that it would be me who finally unleashed him on America, but deeply honored to have done so. I do not know why it has taken so long. I can understand why some UK writers, who are perhaps less accessible (or perceived as less accessible) take a while for their reputations to reach a specific gravity before US houses will take a chance on them, but why Meaney's work, which is highly-accessible, fast-paced, action-packed, and heavily laced with karate, sword fights, and pistol duels in addition to rigorous scientific extrapolations, wasn't snatched up on first sight is beyond me. While we're on the subject, if you appreciate what we're trying to do, please wait for the US editions. Some folks online have been encouraging ordering from overseas, and people who do that are directly impacting my ability in a very real way to bring more great UK and Australian writers across.

LA: Oddly, I just contributed a piece to the April 4th issue of Publishers Weekly on this very topic. Without re-treading here, I would say that while fantasy is perhaps encroaching into the science fiction market, there is a good deal more of either genre being published today, by big and small houses, than there ever was in the Golden Age. In a broader sense, I believe that statistics bear out that while a smaller percentage of the overall population reads today than has in years past, the actual population increase means that in sheer numbers more people are reading than ever have before. Personally, I don't have a philosophical problem with the rise of fantasy and am overjoyed at things like the success of works like Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell. I do, however, see the historical and ongoing importance of science fiction in providing a platform for expressing a worldview in which rationality and ideas of reason and tolerance pervade. Nor can I stress enough how significant SF is in communicating same to each new generation. As a reader, I am a fan of both forms, and what I really lament is the takeover of SF/fantasy by mediocre SF/Fantasy. I see too many works that spoon feed their audience, while more challenging fare languishes in the ever-growing competition for consumer attention. I want my fiction smart—whether that's scientifically smart or literarily smart. I want my science fiction and my fantasy to stimulate, to educate, to elucidate, to provoke and instigate. RK: What are your thoughts with regards to horror fiction? LA: My thoughts are that you are unlikely to see horror coming out of Pyr. This does not mean that I don't like or respect horror, or that I wouldn't like to see the genre return to a state of good health, but only that it is not appropriate for our line. RK: Why do you and Prometheus think this is a good time to start a new speculative fiction imprint? LA: Prometheus had already been testing the waters with a few isolated fiction offerings. They wanted to expand their range, and were advised to choose a niche rather than a mainstream fiction category. They felt there was some correlation between "science" and "science fiction." Imagine that! RK: Indeed. What holes in the SF&F world do you see Pyr filling? What needs will you be answering? LA: I don't so much see definite holes, in the sense you mean, as I believe there is always more good material than there are outlets for same. However, each and every outlet, I do believe, does need to labor under a clear vision. Every editor starts from his or her own aesthetic tastes and judgments and works outwards from there. And yes, as you point out in your introduction above, editors do play an important role in what readers are exposed to. For my part, I have very defined tastes, and I am very much interested in science fiction as a dialogue. I'm encouraged when I see the success of smart science fiction and fantasy writers like Charles Stross, Cory Doctorow, and China Miéville and believe that genius need not labor in obscurity. It's true that Forgotten Realms novels are outselling a lot of the genre, but Susanna Clarke is outselling them. It may be harder to score when you skew smarter, but not impossible. If there is a defining vision to Pyr, it is that I hope our books, whether hard science fiction, imaginative fantasy or wild space opera and military SF, are always perceived as being smart. I want to work with writers whose prose and ideas always clocks in above the average. I'm not saying we'll achieve this 100% of the time, or that this will always be the perception our readers take, but I've acquired 27 books thus far and I don't think I've let the side down yet.

LA: Recently (and by recently I mean last year or so), I heard both Gardner Dozois and Gordon Van Gelder, two men I admire greatly, declare separately that they were NOT Campbellian editors. By which they meant that they published a large selection of diverse material across a broad range of subgenres and themes and did not actively seek out or encourage work of a specific nature or work addressing a specific agenda. I understand this position and I see how it works for a monthly short fiction digest. I am the exact opposite. More to my style, I also heard Robert Silverberg say that he used his famous New Dimensions anthology series to "prune" science fiction back to what he thought it should be, in effect saying "this and only this constitutes relevant science fiction in my opinion." I would like to come forward and confess that, yes, I am a Campbellian editor. Each of my Roc anthologies has been an original anthology, expressed around a very definite theme, with a specific agenda. In the case of Live without a Net, I was reacting directly to what I felt was a preponderance of post-cyberpunk in American science fiction in the year 2000. The anthology was a deliberate attempt to counter that trend in some small and useful way. If I may use Chris Roberson as an example: I met Chris as part of a group of writers at the World Fantasy Convention in Montreal, and invited him, along with that group, to submit to Live. Whereupon I promptly forgot him completely. Then, "O One" came in, and I started to pay attention. I realized it would be a highlight of the anthology. The story is about an alternate world dominated by a Chinese empire. In the backdrop to the story, but by no means essential to it, it is mentioned that the Emperor of China is interested in space travel. When Argosy came along, I called Chris and told him I wanted to see the continuation of the Chinese conquest of space (specifically Mars) and if he would write that story (and only that story) as a novella, I would publish it in Argosy. Chris, at the time, had no plans to continue his Chinese tales, let alone their tales of space, but in the process of exploration that led to the requested story, he crafted two others. One of which, "Black Hands, Red Hands" appeared in Asimov's to great acclaim, and one of which is slated to appear in Postscripts. When I left Argosy, Chris withdrew the novella, but it has since found a home at PS Publishing. Look for it—it's called "The Voyage of Night Shining White." It will feature a stunning cover by Stephan Martiniere, and I have no doubt that it's going to be one of the most talked about novellas of its year and will certainly make the Hugo ballot. Furthermore, there is a story in the third Argosy that I would be inordinately proud of had circumstances gone otherwise by Charles Coleman Finlay. Charlie sent me three perfectly good genre stories that I rejected in turn before I told him that what I really wanted to see was a mainstream tale from him. He went away and wrote his first such piece on commission – "Still Life with Action Figure", and it's nothing short of incredible. Meanwhile, I have suggested no less than three books to Paul Di Filippo that I'd like to see specifically from him, and if he ever takes me up on one of them, I will publish it.

LA: I have a friend in Hollywood who works in children's animation. She's been in development at Disney, Nickelodeon, and Klasky Csupo, and she always maintains that she is only interested in projects that have to be animated, that if a script can be realized with live action then it should be. I apply something similar to my SF. If a story can survive without the speculative element and is only using the science fiction as backdrop, then I'm not interested. But let me twist this a little away from vision and towards needs. I'm hoping Pyr will stay slanted towards science fiction over fantasy, while publishing engaging and intelligent offerings from both genres. I have a real need for hard science fiction. I see more of that coming from Britain than America right now and I'd like to do something about it. When I solicit hard SF from agents, nine times out of ten what I get in return is military SF, and that's not the same thing. At the same time, my father raised me to believe that no one spins the English language with as much eloquence as the Brits do, and consequently I'm tough on bad prose. The combination of hard SF with eloquent prose may narrow the field over here, but that's what I'm shooting for. RK: Tell us about the hiring/"bringing aboard" process? Did you have to relocate? LA: Nope. They were extremely helpful in allowing me to remain in Alabama. I travel a lot, but having a comfortable home base for me and my family is important, and the nature of this business and the singularity of the Internet means you really can do it from anywhere. Kudos to Prometheus for realizing that. RK: Are you looking for material from new writers? If so, how can a new and un-agented writer best approach you? LA: It's very hard for an un-agented writer to approach me, I admit. This field attracts a lot of hopefuls, and while many of them are quite talented, their numbers are such in the greater mass of the slush pile, that if our doors were wide open I would be buried alive. I do not use readers. I do not believe I could teach or impart my tastes, and while I am hand-selecting everything, I must have some sort of filtration process in place or my job would swiftly become impossible. That being said, I have a brand new writer named David Louis Edelman who has never published anything in the field and while he came from an agent, not one experienced in SF&F. David is amazing. You'll meet him in our third season, and I'm expecting great things from him. Other than that, the best way for an un-agented writer to approach me is to publish something amazing in the short fiction market.

LA: Honestly, with the current state of the magazine field, I don't think it would make good business sense for them. That being said, Prometheus' sister organization, the Center for Inquiry, publishes a great many magazine publications (such as the Skeptical Inquirer), and if they ever did want to go in that direction, I'm their man. I love short fiction magazines and would love the opportunity to work in that area again. RK: The Pyr website now serves primarily as a catalogue and advertisement. Do you foresee turning it into something more? LA: Absolutely. Currently, we've got three author Q&As, several chapter excerpts, and an entire novella by Sean Williams that preceded his novel, The Resurrected Man. I hope to be able to continue to add content as we grow, possibly exploring audio interviews, ancillary book information (maps, appendices, etc…) and making PyrSF.com more of a "destination" site in its own right. RK: With 'Here, There & Everywhere' and 'The Prodigal Troll' you've undertaken the unusual, but welcome strategy of simultaneously issuing the trade paperback and hardcover versions of the book. This is done in the UK, but not in the US. What gives? LA: This is an interesting experiment, and one that I'm very curious to see play out. I, for one, am a collector who will never buy a paperback if a hardcover is available, but I'm aware of the importance of the trade and mass market paperback in the market. I'm glad you welcome the strategy, and I hope it pans out. It's something I'd very much like to repeat if we are able. And we are already slated to do it again in our second season for George Zebrowski's Macrolife: A Mobile Utopia. RK: Pyr is already slipping away from a strictly science fiction catalogue. Are there any limitations on what you're willing to publish? Will you publish horror fiction? Non-fiction? Graphic novels? Comics? Is there a piece of utterly mundane literary fiction that you might consider publishing? Will Pyr be doing media tie-ins? LA: Nope, nope, nope, nope and nope. That being said, the future is unwritten, and I did inquire about novelizing a failed script from a big SF media franchise but found it was not an option on their end. Astute readers can probably guess whose. RK: Pyr is competing head-to-head with huge New York publishers for a slice of a diminishing market. What will you do to ensure that you survive? LA: More interviews on the Agony Column? I'm sorry; it's 1 AM here now. We're busting our hump to get good books to readers and to make sure people know they are there. If you build it, will they come? RK: What advantages do you have over such operations? LA: We don't have to have exactly the same numbers they do to consider ourselves a success. RK: What disadvantages do you have facing them? LA: We still need numbers. But I don't know that we have disadvantages. Our distribution is excellent, and the last thing the average consumer looks at when browsing is the logo on the spine. I don't think I ever noticed them until I got into the business. RK: Tell us about distribution and bookstore placement. What are you, as editor, doing to ensure that your books are easily bought and found by readers? LA: This is all to Prometheus' credit. They've had a decades long relationship with Barnes & Noble, going back to way before such was important. They've got good relationships in place with all the major chains and media/review outlets. And we're getting a lot of love from the independents and the core community. Our books really are everywhere in the US, and I'm thrilled with the almost overwhelmingly positive reviews we're getting from Publishers Weekly, Entertainment Weekly, SciFi.com, Locus, Library Journal, Kirkus, as well as numerous websites and regional papers.

RK: Tell us about your relationship with chain bookstores and independent bookstores. LA: While you can't survive without the chains in this day and age, I am adamant that we won't neglect the independents. They are dwindling, true, but they are absolutely vital. They represent a knowledge base you cannot get from the corporations, as well as a (two-way) connection right into the core community. Stores like Borderlands, Dreamhaven, and Mysterious Galaxy are essential and I encourage everyone to support them. RK: What more would you want readers to know about Pyr? LA: I'm thrilled beyond words to be publishing the US editions of the Hugo-nominated, BSFA-winning River of Gods by Ian McDonald and the Aurealis-winning, Ditmar-nominated The Crooked Letter by Sean Williams. These are two tremendous novels, and I think they are going to blow everyone away. Finally, for you linguists out there, we're pronouncing it "Pire" like "fire," but true scholars know it's probably closer to "peer" in the original Greek and are welcome to use that pronunciation and feel superior. Thanks very much. It's been a pleasure. RK: Thanks, Lou. And readers, looking for links of interest can follow on to... Lou Anders Home Page Pyr Homepage Prometheus Books Homepage

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||