|

|

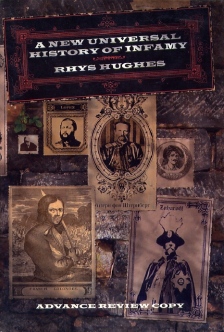

Rhys Hughes

|

A New Universal History

of Infamy |

During the Middle Ages, the only road maintenance carried out in England was by monks. Pilgrim routes were cleared for the benefit of devout travellers. When Henry VIII closed the monasteries, this work ceased. By the end of the Sixteenth Century, there were no easy roads in the entire country. Rutted mud tracks and overgrown paths made journeys by coach a hazardous and slow business. They also provided opportunities for bold robbers on fast horses. The highwayman was born. The first on record was Gamaliel Ratsey, son of a lord, and former soldier in the Irish campaign of the Earl of Sussex. He roamed East Anglia with a sack on his head and slits for his pitiless eyes. Later he constructed a mask in the shape of a hobgoblin with enormous ears which tended to catch on branches. He was knocked to the dirty ground in more than one forest chase. But he eluded justice for several decades, until, typically, the treachery of a friend delivered him to the clumsy hangman. Another early highwayman was John Clavel, who altered his disguise for each attack. His favourite spot for an ambush was Gad's Hill on the London to Dover road. He bribed the landlords of local taverns and inns to shelter and protect him. His skill at impersonating judges, bishops, nobles, ambassadors and politicians was deemed remarkable. His luck ran out when he accidentally dressed as himself and tried to rob a carriage near Rochester. The passenger was a distant relative who recognised his true face and reported the incident to Clavel's stern father. An arrest followed. But the hangman was cheated of a victim on this occasion, for the court accepted an appeal for mercy. The prisoner was granted a Royal Pardon on condition that he write a treatise advising passengers how to avoid being robbed on the road. He was also required to serve a year in the army against France. His book sold well and he retired in luxury in 1642, dying just a few months later. The third pioneer of this profession was Thomas Sympson, one of the few who survived to a ripe age before his capture. He often wore a skirt and preferred to be addressed as 'Old Mobb'. He rode sidesaddle whenever possible and enjoyed a reputation as a gentle spirit. He rarely murdered his victims, never tortured them and frequently blew them kisses. He was even willing to accept cheques. He once robbed Sir Bart Shower in Devon and requested a money order for £150. Binding his victim and storing him under a hedge, he rode into Exeter and cashed the note at a goldsmith's. Then he returned to free Sir Shower. Although he ended his career at the end of a rope, still garbed as a woman, his total number of hold-ups was higher than all his competitors save one. It was noted with astonishment at the execution that the official hangman seemed to be wearing lipstick on his collar. Sympson had buried the majority of his loot. Potentially, he died very rich. He never married. Other Names Thereafter, every disinherited son and gambling debtor wanted to try his luck on the road. There were lady highwaymen too, highwaymanesses, angry and vulgar, smoking tobacco and learning to cheat at cards and duel with double barrelled pistols and sabres. Mary Frith was one; Maud Merton was another. Mary knew how to spit across a wide room. Maud could puff eight pipes in one mouth. Very different from this pair was Catherine Ferrers, wife of a lord, rich enough not to rob travellers, but much too bored to resist the adventure. She used a secret passage to move from her bedroom to the grounds of her manor house. The Royalist highwaymen, Captain James Hind, Thomas Allen and John Cottington, decided to combine crime with patriotism, assaulting mostly Parliamentarians and sundry anti-monarchists. They once made an attempt on the coach of Oliver Cromwell, but his guards killed Allen and chased Hind and Cottington off. Hind was finally captured at Worcester in 1652. He suffered the dreadful punishment of being hung, drawn and quartered. Gold coins spilled out of his chopped bowels. Cottington was apprehended in 1659. He was luckier in his designated agony. He bribed the judge at his trial and was merely sentenced to be strangled with a cord made from the tails of twelve diseased rats. The strangest pair of highwaymen to ever circulate around the roads of a perilous England were undoubtedly Guy Halfaface and Double Pugh. In accordance with a neat destiny, they paired up one midnight on Hounslow Heath. Guy lacked most of his skull, having lost it abroad, probably in France. Pugh had a spare one growing out of his shoulder. He was in fact two men in one body, conjoined twins, almost completely superimposed on each other, with just the surplus head to disrupt the alignment. There was no need for Guy to wear a mask: the mass of bandages which held his damaged mind in place was both a disguise and a distinguishing mark. As for Pugh, two masks were necessary. Both men were unsuccessful at robbery until they found themselves victims of a mutual hold-up. Neither knew where to aim his pistol. They became partners. They shared the hatred of commoners and the mistrust of outlaws. But they operated in tandem for a year, before Guy's bandages were caught in thorns as he rode through undergrowth. They unravelled and his exposed brain was pecked by magpies while he was still in the saddle. Pugh continued alone for another month, but his forgetfulness proved to be his undoing. He neglected to mask his second head. It was later recognised in a tavern and sentenced to be hung. His main head was acquitted due to lack of evidence, but it eventually starved to death as he dangled from the gallows. Less desperate and more robust, William Davis kept his villainous activities secret from his wife and children. They believed that he was a simple farmer who ploughed all his fields at night with a blunderbuss and cutlass. One fateful evening, after drinking too much ale, he tried to rob a coach with a trowel and bag of carrot seed. He was chained to a post on Bagshot Heath and his clothes were filled with earth and planted with root crops. He was regularly fed and watered by his wife, but within a season he was fully crushed to death by the growing parsnips in his shirt and breeches. Inevitably his corpse was stolen by graverobbers and sold to vegetarian witches in Surrey. The most glamorous highwayman of all was an import. Claude Duval was born in Normandy and decided to work the roads of England because his accent would charm the female passengers of the coaches he robbed into parting with their jewellery without a fight. He was not mistaken. He quickly earned a reputation as a dancer, singer and kisser, a dandy who charged helpless husbands £100 a time for the privilege of watching him seduce their wives in roadside ditches. Unusually, he retired from the job before the authorities terminated his career for him. Unwisely he chose alchemy as his next profession, and expired after falling into a vat of molten lead which he planned to transmute into gold with the aid of a forged spellbook and a jar of powdered unicorn horn. The Defaulted Wife The only highwayman who ever amassed more loot than Thomas Sympson lived half a century later. Unlike 'Old Mobb' he had no compassion or interest in fashion. He was a brute of the utmost gloating, a drooling idiot who yet possessed enough aptitude to arrange a beneficial image for himself. He was born Richard Dick, but he instinctively understood the advantages of pilfering the identities and achievements of other robbers. There was a local highwayman by the name of Dean Pinter who rode a mule instead of a horse and thus enjoyed a brief career. Richard stole his surname and rearranged its two syllables, condemning its original owner to historical oblivion. A misspelling completed the theft. Thus Dick Turpin emerged not from a womb but from his own unthinking head. His first act as an outlaw was to stab the only schoolmaster in his village and abduct his pencils, which he subsequently ate. The county of Essex was notorious for the low level of education of its citizens. Turpin decided that they were too clever for him and so he moved to London. By the time he arrived, he forgot he was supposed to be a highwayman. He secured employment as a butcher. The man who gave him the job was a smuggler of venison, which was a meat only licensed to the teeth of aristocrats. Turpin was sent into the forests beyond London to kill deer and bring them back hidden beneath cartloads of vegetables. He discharged his duty admirably but not without a measure of confusion. It later emerged that he attempted to rob the deer before shooting them, demanding that they hand over their purses and gems. On one occasion, he rode back on a deer, with his dead horse in the cart. His employer knew a doctor who agreed to examine Turpin. The diagnosis was 'brain pox' and the recommended cure was the wearing of a hat made from a hedgehog. The patient was not allowed to remove it even in bed. Turpin used it as an extra pocket, impaling small objects on its spines. In June 1727, returning to his lodgings after work, he lost his way in the fog and entered the wrong house. The woman who lived there was so shocked by the appearance of the dirty rogue she was unable to protest. This condition persisted for the remainder of her life. Dick Turpin was forced to assume he was her husband. There was no other explanation for her existence in his abode. He could not remember the wedding, but that was a minor detail and could be shrugged off. She cooked him a meal and they slept together that night. The bedroom was full of mirrors. In the morning, he rose and tried to demand money off his own reflection. Then perceiving there were more of them than him, he backed away. Perhaps he slipped on a rug. At any rate, he struck his head on the sharp corner of a chair. The result of this blow was temporary amnesia, and a doubling of his intelligence, for he completely forgot he was incompetent. Even so, he remained stupid and vile. The Lunatic Ride Exactly a year later, his employer, wealthy on the profits of Turpin's hunting of deer, bought his protégé his own butcher's shop. The gift was received with panic. Turpin understood only that his responsibilities had increased. His initial reaction was to raise money to bribe them to shrink again. Banditry against humans seemed the only answer. He fled with his wife to the marshes of Canvey Island, a desolate region settled by other robbers. One by one he relieved them of their savings. Rumours filtered back to him that he was the most wanted man in England. After sunset, lanterns fixed to long poles carried by men on stilts flickered over the stagnant waters. Bounty hunters were searching for him. Within a month, he amassed enough lamps to open a lantern shop. He dwelled in a reed hut which he built with his own wife's hands. It was illuminated on the inside by wills-o'-the-wisp which flared and moved across his sodden rugs. By this light, she read him books. In such a fashion, Turpin came to learn of his predecessors in the business. The tale of William Nevison was his favourite. Nevison earned himself the nickname of 'Swift Nick' for one daring exploit. Following a robbery at Gad's Hill, Kent, he galloped all the way to the city of York in fifteen hours. The distance was approximately 200 miles. Considering the average speed of 14 miles per hour for a healthy horse, it is clear that Nevison must have changed steeds many times. Nearly two centuries later, George Osbaldeston, a champion rider, duplicated the feat using no less than 28 different horses. The point of the ride was to exclude Nevison from suspicion. When he was arrested for the robbery in Kent, he called witnesses who swore on oath to have spoken to him on the same day in York. The court judged it impossible for a man to cover the distance between the two locations in so short a time. They acquitted him. It was a ploy which might only work once. Turpin comprehended nothing of Nevison's reasons for the adventure. He cared only for its superficial excellence. He decided to claim it for his own. He painted his wife with tar, fixed a hairy tail to her rump, ordered her to walk on all fours and started referring to her as 'Black Bess'. Then he led her back to London. She was his horse, he insisted, and had carried him from Kent to York without pausing at all. Although sixty years had passed since Nevison accomplished the stunt for real, the public swallowed Turpin's version of events. Nevison was forgotten. In 1834, the historical novelist, William Harrison Ainsworth, published his first book, Rookwood, which supported all Turpin's lies and added a few of its own. This story established him in the public mind as a bold and romantic hero, an outcast only because of social injustices and the corruption of the law. The highwayman once buried a bag of silver coins in a field. Perhaps he guessed that any future writer who found it would regard it as fair payment for a positive literary portrait. Ainsworth's house was constructed on that site. Yet Another Turpin Already the toast of London high society for his supposed sophistication and chivalrous qualities, Turpin had a lucky encounter on Putney Heath which enhanced the mirage of his character considerably. He tried to rob another renowned highwayman, Thomas King, who laughed in his face at the irony. The mistake proved advantageous to Turpin. They decided not only to team up, but also to swap identities. King was a genuine hero of the roads, stealing from the rich and giving to the poor, with a modest 25% handling fee. Turpin was an indiscriminate butcher and buffoon. Both were wanted by the authorities. Clearly if King pretended to be Turpin, and Turpin to be King, they might be safe from execution, for they would be arrested, charged, tried and sentenced under incorrect names and thus could not be legally hung. It was an inspired idea. Unaware that Turpin was a brute, King assumed with everybody else he was a dashing hero like himself. The final result of this exchange was a perfect reputation for the monster and an appalling one for the gentleman. Turpin moved to a second hut in the depths of a forest and emerged only to slaughter travellers who alerted him by breaking dry twigs with the hooves of their mounts. King roamed the whole of England, bowing to ladies and feeding orphans. Turpin licked gore from his hands. King was invited to weddings and birthdays. Turpin dressed in mud and leaves and resolved not to speak in words. King wrote exquisite poetry and sang to a guitar. Turpin rotated all his loose teeth in their sockets until they faced backward and went blind in one eye because he forgot to blink it. His amnesia had worn off. He was better, and thus much worse. King felt there was nothing amiss with men who wore pink, and encouraged families from the poorest countries in the world to emigrate to England, helping them fill in the application forms. Turpin grunted his wife to death. King sniffed flowers. Turpin did not. Everything now attributed to Turpin was the work of King. The smile and manners, sensitivity and sense of honour. King continued to sanctify the name of Turpin, acting on the misunderstanding that Turpin was doing the same for him. One morning, an hour before dawn, a lone horseman with a sack of gold and food deliberately rode off the designated trail in an isolated wood. Turpin heard the snapping twigs and leaped out of his hut with his blunderbuss. He had brought no shot with him, so he plucked the spines out of his hat and pushed them into the barrel. When the stranger came close, he discharged this weapon directly into his face. The victim did not die immediately. He fell to the ground, gasped that his name was Dick Turpin and that his blood had stopped circulating. "I have pins and needles in both cheeks," he cried. Then he added that he had heard about a very poor man who lived alone in the forest and that he had come with money and cakes as a gift. He said no more. The real Turpin stood and scratched his head, the first time he had been able to do so without puncturing his fingertips. He decided to look for this poor man in the hut. Perhaps he could rob him. He strode off in a northerly direction, because he had once been told that the north was higher than the south, and he wished to have a clear view of anybody who might be pursuing him. To his surprise, the way was mostly downhill. The hut must have been very elusive or cleverly disguised. After a week, he came to the edge of the forest. His hunger rapidly increased. He saw no reason why he could not catch and cook his own meals. He met a tinker selling kitchen implements. He licked his lips. The entire world can be a hut, he realised, and very poor men are everywhere. The Jump Turpin was arrested in October 1738 on the charge of stealing a grouse and trying to boil a saucepan over it. He was deemed mad and his thumbs were severed in an attempt to cure him, for it was widely believed that picking one's nose was the sole cause of insanity. Showing few signs of improvement, he was sentenced to death, together with the grouse, at the end of March 1739. The jury recognised him as the depraved Thomas King. It was lamented that he had none of the courage, style or decency of the famous Dick Turpin. He slept through most of his execution, awakening in time to jump from the scaffold in order to break his own neck and avoid a slow strangulation. The force was not great enough. It did not matter. He was heard to snore loudly as the mob tugged at his feet to hasten his end. He had fallen asleep again. |