|

|

|

This Just In...News from the Agony Column

|

03-04-05: 'Cast of Shadows' by Kevin Guilfoile; 'The Reluctant Spiritualist' by Nancy Rubin Stuart, Laughin' Boy Cover Art Exclusive |

||||||||

SF

Slips into the Mainstream

So one has to wonder if the hand-wringers are including books along the lines of Kevin Guilfoile's 'Cast of Shadows' (Alfred A. Knopf / Random House ; March 1, 2005 ; $24.95). It really doesn't matter how you slice it, this is a science fiction novel, even if it looks like a mainstream thriller, walks a like a mainstream thriller and talks like a mainstream thriller. The premise is disarmingly simple. Davis Moore is a fertility doctor who gives parents the ability to conceive by creating cloned embryos. Moore's daughter is brutally raped and murdered. When the police return her belongings, they also accidentally hand over a sample of, umm, the killer's DNA, so to speak. Bad form that. And a bad person to make this mistake with. Moore decides that he wants to meet and punish his daughter's killer and he's in a position to do so. With the reckless abandon that makes grant-grabbing research scientists, he decides to clone his daughter's killer. Soon, a killer is born -- literally. Or is he? Guilfoile brings some pretty odd but encouraging experience to the novel. He's well known as a humorist, and has work in the all-too-excellent McSweeney's compilation 'Created in Darkness by Troubled Americans'. With John Warner, he hit the bestseller list lampooning President George W. Bush in 'My First Presidentiary: A Scrapbook by George W. Bush'. He's a commentator for National Public Radio, and his whole humor gig began when he got published on the McSweeney's web site. Now, to my mind McSweeney's generally indicates the mark of a fully competent and indeed inspired writer. But the leap from silly humor to what used to be called "social science fiction" (remember that, folks?) is well, rather on the breathtaking side. Still, one hopes that some of the humor he specialized in informs this potentially heavy-handed subject. When asked about 'Cast of Shadows', Guilfoile indicates, appropriately enough, that the novel itself is the bastard child of 'Frankenstein' and the OJ Simpson trial. And because cloning is strictly illegal in the reality we currently inhabit, he had to step aside to a version of our world where cloning is legal. So not only are we getting speculations on the social impact of technology-style science fiction, we're also getting what is essentially alternate history, minus some of the gimmicks that the usual alternate history novel gets itself up to. In fact, novels that conveniently and significantly alter reality to make speculative plots less problematic are becoming even more common, and probably deserve a sub-genre of their own. They're not alternate history so much as convenient history. Guilfoile states that he "wanted the world at the end of the story to feel not too different from the present" and that he "did the minimum research that I could" to create the novel. While all this may strike one at first as cheating in some way, in reality it's just smart writing. By carefully sweeping aside many of the usual concerns of science fiction and focusing on what would give him the simplest plot and the best access to his characters' feelings, Guilfoile has indeed done what smart science fiction writers often hold as an ideal. He's put characters in riveting moral dilemmas front and center and backgrounded everything else. On one hand he may have a breakaway best-seller on his hands, pleasing to genre fiction readers and mainstream readers alike. Or he may have managed to create a neither-fish-nor-fowl book that manages to evade all readers. To my mind, the critical element is whether or not he has successfully incorporated the humor into the novel. It might prove to be unnecessary. It might prove to be vital. To my mind, humor always leavens serious thought, and keeps it from being lampoonable. In any event, the upshot of all this hand-wringing is that another science fiction writer has arrived on the scene, bearing with him a newish genre -- convenient history. Readers should look out for this. There will a lot more coming down the pike, as more and more writers who were once happy to be outside the science fiction genre twig to the delight of asking, "What if?" Answering that question is a whole lot more fun if you just wave your fictional hand and make the world go away. |

||||||||

The

Life of Ghostbusted Maggie Fox

But what would the faith-based society think if I told them that two toe-cracking sisters led not only our nation but much of the world to have faith that their toe-cracking was evidence not of brittle bones but of life after death? Surely such a thing could not come to pass. Faith is inviolable, personal, and can't be manipulated, can it? Oh yes it can. Nancy Rubin Stuart's 'The Reluctant Spiritualist: The Life of Maggie Fox' (Harcourt ; February 15, 2005 ; $25.00) offers an all-too-sobering look at a craze that swept the nation and the world, only to be ultimately, finally exposed by the woman who started it all with the toe-cracking pranks of a young girl. In 1848, fifteen-year-old Maggie and her sister Katy created rapping sounds by cracking their toe joints underneath the table. They managed to convince their parents that their farmhouse was haunted. Within a couple of years, they were playing the big time in New York, convincing Horace Greeley and James Fennimore Cooper that they were tapping and rapping their way into a supernatural realm that allowed them to communicate with the dead. And they didn't even have a Guide to Cold Readings like our current crop of psychics has. 'The Reluctant Spiritualist' offers a look at the life of the Spiritualist movement as charted via the life of its founder and leader, Maggie Fox. It offers all the great ingredients of speculative fiction minus one -- the fiction. In this case, the work is all the better for its absence. |

||||||||

| Laughing

Boy Cover Art by JK Potter Last week, I talked about Bradley Denton's 'Laughing Boy', forthcoming from Subterranean Press, and mentioned that, not surprisingly to my readers, the JK potter cover art was one of the things to look forward to. This week, Mr. Potter himself kindly presented evidence of this by sending me a number of his wonderful illustrations. Below are the mini-mockups, but for those of you who thirst for the real deal, just click on an image to go to the gallery with the full size images. Thanks Mr. Potter, Mr. Denton and Mr. Schaffer -- this is yet another book truly worth waiting for! Click here to open up gallery view!

|

||||||||

|

03-03-05: Paul Di Filippo 'Harp, Pipe and Symphony', Bryn Llewellyn 'The Rat and the Serpent' |

|||||||||

Prime

Time

But it's told not just by the talented Paul Di Filippo; it's told by the talented teenaged and twenty-something Paul Di Filippo. In a brief forward to the book, he explains that he conceived of the novel at the age of eighteen and wrote it ten years later. "Both the teenager who initially imagined Thomas Rhymer's adventures and the young man who transcribed them are charming and eccentric strangers to the fifty-year old writing this preface. Still, the present author admires them both -- from a suitable distance -- and has resisted overmuch tampering with the fruits of their hard labors. Said fruits include meetings with monsters and humans, though it may be hard to tell the two apart. But since youthful verve informs even the current Di Filippo's oeuvre, this is something to really look forward to. Clocking in at a compact 207 pages, this is a fantasy that must have been written before the doorstop model was de rigueur. It may have come from the trunk but it itself not a trunk, and for that alone we will be thankful. The quality that oozes from whatever Di Filippo touches we'll take as icing on the cake.

'The Rat and the Serpent' claims to be a novel written in back and white, which, the wry might observe, is not particularly uncommon. But it claims to be a novel written in black and white in the same way that a movie is filmed in black-and-white, and that indeed is both uncommon and borne out by the crisp prose. What might not be so clear is that this steampunk scenario has a heavy science fictional backbeat. Mavrosopolis is not be found in some forgotten nineteenth-century English backwater. You're going to have to hop in Wells' time machine and press the forward button to get there, I do believe.

Now that's a fascination I happen to share, though I'll also confess that my wife does not share it, and has carefully removed most of the ivy that used to cover our yard. Alas, the only premonitions I receive come in the mailbox and suggest that a late payment fee will be added if what is predicted does not come to pass. I'm saying that as if it is a good thing. And looking for that damn time machine. |

|

03-02-05: Black Blossom by Boban Knezevic |

||||||

Night

Blooms from Serbia

Perhaps I should explain. Bearing copyrights in 1993 and 2004, I'm guessing -- totally guessing -- that the original Serbian edition was published in 1993 and that the Prime Edition is available as I write. If not in fact, then in theory, and in any event I've got to guess that it can be easily ordered. In the simplest, strictest sense, 'Black Blossom' is a heroic fantasy. A warrior must defeat a warrior sorcerer and escape from the realm in which he finds himself trapped. Dont expect anything like any Western fantasy you've read recently though. There will be no windy political lectures here, no ab-flexing heroes. In fact, there will not even be a book in order here.

Cover art is once again courtesy the quite tasteful Luís Rodrigues, who does a lot with a little. But most of the illustrations will bloom in the back alleys of your polluted brain. The combination of an experimental narrative with a very traditional and ethnic fantasy is something far too appealing for me to pass up, especially one so compact as this. Serbia may not be a happy place. It may not produce happy fiction. But just one 'Black Blossom' from the tainted soil may be enough to cause the reader to grow fond of the writer's work. And there's much more where this one came from. Intriguing science fiction, perhaps -- 'The Android's Premonition'. Stranger fantasy, 'The Man Who Killed a Butterfly'. Perhaps this is only the beginning of the invasion. |

|

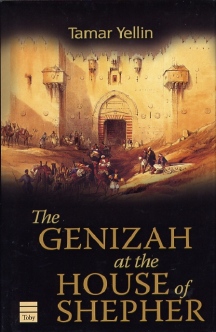

03-01-05: Tamar Yellin and 'The Genizah at the House of Shepher' |

|||

From

Yorkshire to Jerusalem

Tamar Yellin is many things, but she's evaded simple. Born in England, she's the daughter of a third-generation Jerusalemite. She's a teacher and a lecturer in Judaism. And she's the product of a family history so complex it leaves many a novel behind -- and only her novel, 'The Genizah at the House of Shepher' (The Toby Press ; April 7, 2005 ; $19.95) measures up to her reality. That doesn't make the reality any simpler, but it makes her novel all the more compelling. Let's start simple, though. "Genizah" is a Hebrew word for hiding place, particularly the hiding place of old or sacred documents. 'The Genizah at the House of Shepher' is the saga of a Jerusalem family stretching back a hundred and forty-five years and four generations, a thriller about a missing biblical codex that leads to a search for the true text of the Bible. And while so many books that deal in historical mysteries get by on research, few writers are able to bring the personal experience and passion of Tamar Yellin. Because in many ways, the House of Shepher is the House of Yellin. In an essay on the Toby Books website, Yellin speaks of how her family was involved in translating the Aleppo Codex, considered to be "the most perfect text of the Bible in existence". She embarked on a journey to discover their involvement, and out of that journey came her first novel. 'The Genizah at the House of Shepher' is the story of Shulamit, a Biblical scholar from England who visits her grandparents' home in Jerusalem only to become embroiled in the search for The Shepher Codex, a manuscript discovered in the attic. As she traces the history of the manuscript, she traces the history of her family, from Babylon to Jerusalem, from her great-grandfather to the mysterious stranger named Gideon who set her on the journey in the first place. Written in short chapters and the kind of careful prose that makes personal novels so compelling, Yellin's novel gets the reader up close and uncomfortable with the vast history that looms over our world. The protections we put in place to keep ourselves safe from the past crumble so easily that they might as well not exist. Confronting our past, our history requires more courage than that required to merely acquire knowledge. Everyone has a past, and that history forms a ceiling upon which we project our self-identity. Pull it down, and the void beyond may bring in things best avoided. For those of us looking for a parallel, the only books I can think of to deal with a similar subject in a similar manner are those by former CIA operative Edward R. Whittemore. His five novels -- 'Quin's Shanghai Circus' and the Jerusalem Quartet -- the re-issues of which are apparently still available from Old Earth Books -- also offer a glimpse at a quixotic search for the "true Bible". And, like Yellin's novel, they offer the pleasure of a jaunt through a deeply personal history. The true Bible, the Holy Grail -- we're all Cervantes' Don Quixote, tilting at windmills. When you tumble through the last illusory wall, all youre left with are yourself -- and your family. There's no hiding from them, ever. Even in a box in the attic. |

|

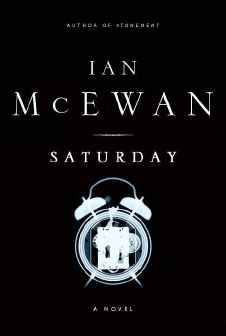

02-28-05: Literary Monday: Ian McEwan 'Saturday' and Haruki Murakami 'Kafka on the Shore' |

||||||||||

|

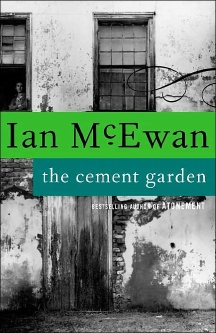

A Brief History of Ian McEwan by Nazalee Raja

In 1975 McEwans first volume of short stories, 'First Love, Last Rites' was published, winning him the Somerset Maugham Award, while its themes of sexual obsession and perversity won him notoriety. The content was deemed all the more shocking for being expressed in McEwans now characteristically familiar concise literary style. McEwans second collection of stories, 'In Between the Sheets', was published in 1978, shocking the English literary establishment once more with its now familiar McEwan themes of adolescent sexual awakenings, the perverse and the macabre. Having read both volumes, I can understand if not agree with the outrage they provoked. McEwan is quoted as having said: "What is strange and subterranean about human nature interest me far more than writing fiction about people accumulating wealth or losing wealth."

In 1980, a television play, 'Solid Geometry', based on his short story of the same name, made the headlines when the BBC banned it, ostensibly for a scene displaying a pickled penis in a jar. It was subsequently published in his book 'The Imitation Game: Three Plays for Television' and has since been shown on British television. In 1981, McEwan was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for his novel 'The Comfort of Strangers', a haunting tale of sadomasochism and murder. McEwans prose style conveys the impending feeling of menace borne out well by the novels climax. In 1987, McEwan's 'The Child in Time', describing the anguish of a young couple following the abduction of their child at a supermarket, won the Whitbread Award for best novel. 'In The Innocent' was published, in 1990, 'Black Dogs' in 1993, neither of which I have read. 'Enduring Love' was published in September 1997 to huge critical and commercial success, setting a trend for his subsequent works. 'Enduring Love' is more optimistic than earlier writings, and in some ways his finest novel. The film of the book was released November 2004. All of McEwans works since then -- 'Amsterdam' in 1998 (winner of the Booker Prize) and 'Atonement' in 2002-- have been very well received by critics and have managed to stay at the top of the Best Seller lists, disproving the theory that literary novels do not sell. As someone who has read and enjoyed the majority of McEwans work I look forward to reading 'Saturday', already a bestseller, his most overtly political novel to date. |

||||||||||

Murakami, Music and Shrines

The best work that I've ever managed to do has been in collaboration with the father of one of my son's friends, guitarist Bill Reed. He and I did two compositions that utilized spoken word tracks from KUSP interviews. One track is 'Burying Freedom' with a vocal sample from an interview that Kathryn Petruccelli did with Isabel Allendé, while the other 'A Million Little Pieces' utilizes material from an interview I did with James Frey, author of the memoir with that title. While shuttling between houses to pick up gear, I once noticed a little shrine that he had on his recording console desk -- a pile of small, Japanese editions of the work of Haruki Murakami. When I asked him about it, he told me that Murakami was his favorite writer, and that he even had the Japanese editions of some of his books, though he couldnt actually read Japanese. While I'd heard of Murakami and had contemplated buying each and every novel as they came out, I never quite got round to doing so. Alas, that's the fate of so much great fiction. But while Bill and I were working on 'A Million Little Pieces', he had just bought the latest (at that time) book from Murakami, 'After the Quake'. He insisted that I read a story in it, and I was happy to comply. After all, here was something I'd been wanting to read being shoved into my hands. Readers of Murakami and this column won't be surprised to learn that the story I read was 'UFO in Kushiro', in which the narrator's wife leaves him with no notice, no note -- she's not there, just like the Zombies' song. Beautifully written, a powerful story, it was also firmly in the genre I like to call "Slit Your Wrists and Hope to Die", those ultra-depressing stories that manage to grab hold of any seeds of depression within and bring the black blooms to flower. Fortunately, it was well enough written that the pleasures of the prose prevented anything permanent from coming to pass.

Murakami is something of a music fan, and the title comes from a song on a 45 RPM record. Remember those? Well, some of us do. Murakami not only remembers, he rhapsodizes. His novel seems to offer some of the constructions one might more reasonably expect to find in music -- riffs, repeat and modify, long lyrical passages with a dirge-like backbeat. For readers who like their surrealism thick and chewy, who like their apocalypses random and already passed -- though nobody noticed in the general haste -- for readers who like reality leavened with a sense of humor and horror, Murakami offers a unique chance to indulge in a novel that looks to be absurd and compelling, weird, yet sunny and accessible. Clearly, Murakami is an acquired taste and a literary taste. He's also verging on a best-selling taste, with this book already in a fourth printing. Of course, that very fact is itself rather surreal. It loops back on itself, and if this precision literary looping appeals to you, the chances are that you might one day form your own very peculiar and personal attachment to Murakami. The shrine is optional but highly recommended. |