|

|

|

This Just In...News from the Agony Column

|

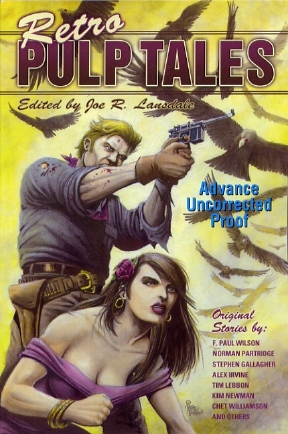

02-17-06: Joe R. Lansdale Starring As Editor of RETRO PULP TALES |

|||

Hot

Monster Alien Gun Hero Action!!!!!

You can credit the work of McSweeney's and Michael Chabon in particular in this regard. The McSweeney's 'Thrilling Wonder Tales' series were really the endpoint of a long evolution, as Pulp Literature rose from the primordial soup and struggled up onto the land. The first gaping creatures to do so were probably those great, classic Bantam Adult Fantasy Titles back in the 1970's. I'll probably never get tired of remembering or writing about buying them off the racks in a local Lucky's grocery store in West Covina, California. Clark Ashton Smith, H. P. Lovecraft, Lord Dunsany -- I still have all those glorious old mass market paperbacks that take work born as 1930's pulp fiction and repackage it as what it actually is; finely-written imaginative literature. But let's fast forward to the matter at hand, this latest work from editor Joe R. Lansdale and Subterranean Press. I first encountered Lansdale as an editor early on in my reviewing career, when I bought 'Razored Saddles' from Midnight Graffiti editor Jesse Horsting, who was working in the San Fernando version of Forbidden Planet. (Just up the street from -- see below for more Book Action!) I ended up reviewing the book for that magazine, and I bet if I went to dig through the stacks somewhere, I could scare up a twenty-plus year-old copy. Lansdale's been taking the pulps seriously for quite some time now. But not so seriously as to drain them of all the fun. This is absolutely critical to the form. For all their rough-and-tumble feel and subjects, the pulps are rather a fragile literary flower. They flourish in a narrow editorial range. If you don’t take the work seriously enough, you can end up with, well, uh, trash. Or no, not really trash, so much as that which has the external appearance of pulp without the generous heart that makes the genre fun. And if you take the pulps too seriously, well then you end up again, with the externals in place but the wonderfully fun life drained out of the stories. (Which is what Lansdale thinks a certain editor has done and says in his intro -- see below for more Editorial Action!) Fortunately, it's not that hard for editors to restrain themselves. Editors who want to publish New Pulps all seem to understand the peculiar mindset necessary and to know the writers who can do the job. And none better than Joe R. Lansdale, who has turned in what seems to me to be a sure-fire hit. Every pulp-based anthology these days starts with an editor's introduction, and 'Retro Pulp Tales' is no exception. Lansdale specializes in, well, besides 'Retro Pulp Tales', he specializes in plain speaking, which he undertakes with gusto in his intro. Will his take on Michael Chabon's anthology be as incendiary as Chabon's introduction to his own collection? It's a lot briefer, very funny and utterly engaging, in an in-your-face sort of way. Well, what else would you expect? The stories include work by writers you’d expect to find here and some nice surprises. Alex Irvine, Kim Newman and Tim Lebbon. Irvine, who doesn't provide an intro to his story, offers 'New Game in Town'; cops, crooks and more than either of them is equipped to deal with. Newman brings on another Diogenes Club story in 'Clubland Heroes', which clocks in at nearly 40 pages. Tim Lebbon wonders in his introduction if anyone ever saw a TV show he used to watch called 'Land of the Giants', and I'm here to say, Tim, you’re not alone and you didn't dream it all up. It was an Irwin Allen production, the guy who did one of my favorite shows as a kid, 'Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea'. So you can imagine what’s involved in Lebbon's 'The Body Lies'. In case you’re wondering what the hell's the matter with me, the answer is, I don’t know. I mean, here's a book that includes F. Paul Wilson's story 'Sex Slaves of the Dragon Tong'. What, like I forgot that I have about a million reviews of Wilson's books in my Review Archive? Sheesh! Zipping back to the front of the book -- oh so appropriate in the circumstances, we have James Reasoner's 'Devil Wings Over France: A Dead Stick Malloy Story'. I'm guessing that's pretty self-explanatory, but I loved his intro. Chet Williamson explains in his intro that he once purchased a flat-bed truck's worth of old pulps, and uses this purchase to his advantage in the more modern-seeming 'From the Back Pages'. Well, modern until you think of some of the old Lovecraft stuff. Melissa Mia Hall's story is titled 'Alien Love at Zero Break', another one of those pulp titles that seems to say it all. But she says she read the original novel of 'Gidget', a name that was once really familiar but now seems really bizarre. Surf's up, alien dudes! Then there's Bill Crider, and damn if the last time I saw that name wasn't in 'Razored Saddles' then I probably deserve one. 'Zekiel Saw the Wheel' brings back my memories of reading flying saucer paperbacks in the 1960's; the "Z" takes me back to that hallowed ground of the spinning rack in Zody's. Al Sarrantonio, currently working with the prestigious and can-do-no-wrong publisher Hill House, took some time from his duties there to spin a Bradburyian tale of 'Summer'. Though given the subject, I'm a bit surprised he didn't amend the title, but then again, that would be a more sixties vibe, and Lansdale's pretty clear in his intro: Pre-60's. More evidence of my advancing incompetence is to be found in 'The Box' by Stephen Gallagher. I've read just about every damn thing he's written and enjoyed the hell out of it. In fact, buying 'Down River' at Dangerous Visions in Sherman Oaks (down the street from See Above) long ago is one of those memories that's just stuck in my brain. 'Incident on Hill 19' by unknown-to-me (up until now) Gary Phillips combines his love of stories that involve science fiction and combat. And rounding things out is 'Carrion' by one of my favorite Subterranean Press authors, Norman Partridge. He tells readers in his introduction that he was going for a Robert E. Howard vibe. That's a vibe I can hang with any day. So that should give you some small idea of why you should buy (or for some readers, I guess, avoid) 'Retro Pulp Tales'. I did note a distinct lack of sensitive poet types, or quiet suburban moms and dads dealing with some family problems. Of course, in more than a few households, pulp fiction has caused family problems. As a teenager I was accused of living in a fantasy world because I was reading H. P. Lovecraft and Edgar Rice Burroughs. And I was to a certain extent. In sixth grade, my friends and I told our parents we were Red Martians from the Burroughs Mars novels. The upshot of all this evil influence? I'm still living in a fantasy world. Bring on the surfing aliens! In Santa Cruz, we'd welcome them even if they did burn us down with blazing heat rays. |

|

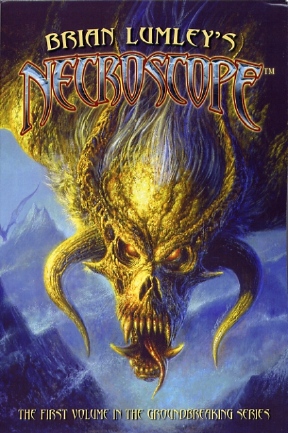

02-16-06: Brian Lumley's Necroscope ™ |

||||||

Subterranean

Press Gets It Right

Ah, the good old days. When horror novels were thick slabs of cheese, when monsters slavered over helpless women and Harry Keogh talked to the dead to find out what the hell was up with a necromancer who had made a bum deal with slimy vampires. So yes, by now you should know about these books. There are, how many? Well, the back cover of this one claims, "More than a dozen sequels." (Sixteen in the series when the final novel, 'The Touch, comes out later this year.) I read the first eight. And I'll probably read the rest, given time. And especially if they look like this new version... And oh, that review, that review. I remember writing it, offering Lumley the highest praise, which was: "Once you resign yourself to enjoy this luridly-written novel, you'll find that it's like those rare "great" B movies--a fast, fun time." It got three stars plus. I mean, you've got some grotesquely horrific monsters here, parasitic creatures that transform humans into slavering vampires. You've got Speakers to the Dead, the Great Majority as Lumley calls them. As much as I love all this stuff, it is not necessarily High Litrachur. That's a Good Thing! And it garnered my first response from an author who was, shall we say, less-than-thrilled to be compared to a B movie. These days the phrase "B movie" barely has any meaning. It's not like anyone could imagine sitting through two movies, unless they’re at a drive in. But I truly thought I was paying the book a compliment. And I still have Lumley's letter. So, have the intervening years been kind to Harry Keogh and 'Necroscope'? I guess so! Fifteen sequels certainly say so. The TM Trademark on the cover says so, even as it forbids you to use Lumley's, well, trademarked terminology. I guess the idea is that although the term lends itself to a general usage, Lumley does have a compelling interest in others not putting that term in the titles of their novels, lest one confuse them or think he commissioned some knock-offs. But most importantly, Subterranean Press says so with this luminous edition.

Now, one of the things I really like about Lumley's writing is that as an author, he sort of inserts himself into the prose and the story. That is, you really get the sense that you're being told a story by a very specific person, maybe that frightening guy in the pub, maybe that gent in the library checking out the Tome Of Ancient Lore. So another welcome addition here is Lumley's own introduction. He talks about the history of the 'Necroscope' novels, gives a brief bibliography of them, talks about working with Eggleton and swears that the final novel, the aforementioned 'The Touch', "will conclude, but definitively, the Necroscope series." He adds that, "And friend, if you got half as much enjoyment out of reading these novels as I got writing them, then I'm satisfied." Mr. Lumley, please be satisfied! I can safely say that I got many, many hours of reading pleasure out of the adventures of Harry Keogh and company. And as for that word you use, "definitively"? I'd suggest that having written a series of sixteen books in which the dead are resurrected in more ways than even the most inventive authors usually manage to dispatch victims unto death, you’d know better than to say that you could definitively conclude this series. For every spell, there's a spell checker and counter-spell. For every series there's a sequel. And if the Great Majority demands it, I hope you'll reconsider...Lest their demands take a form that even Bob Eggleton hesitates to illustrate! |

|

02-15-06: David Mitchell's 'Black Swan Green' |

|||

The

Memory Fabulists

But even these genre groupings allow for a huge range. I've often rhapsodized about how one genre or another allows a writer to do anything and everything. The truth is, any writer in any genre can get away with pretty much anything they want to, if they’ve got the chops to pull it off. So even within the "sci-fi" genre, for example, the range is so wide that we have sub-categories and schools of writers. Sub categories are pretty helpful. You want cyberpunk, you know what you’re going to get. You want military science fiction, again, you know what you’re going to get. But when the going gets vague, as in the world of fantasy, well, you need the help of the writers at work, or critics who can help pull stuff together. So as far as fantasy goes, there was a group of writers who fell under the name New Weird. It is a wonderful group of writers who do stuff just up my alley, and I know that if something is called "New Weird," the chances are that I'm going to like it. The arrival of David Mitchell's new novel, 'Black Swan Green' (Random House ; April 11, 2006 ; $24.95), heralds to me the arrival of a new group of writers that I certainly like and I think my readers will like as well. I was conversing online with a co-worker at KUSP about the novel, and he suggested to me that I might not be so enamored of the book because (and I'm paraphrasing here), "it's not sci-fi, it's a memoir." Aside from the fact that I like a lot more than "sci-fi" (I'm beginning to understand why Harlan Ellison spits nails every time he hears that phrase), I began to think about why a Mitchell (fictionalized) memoir might be just as interesting to me as a science fiction novel. Part of the reason was revealed to me the first time I paged through the novel. I came naturally to the section where the characters were talking about a Stephen King novel. So, of course, as the kids these days would say, "I'm down with that." But there's a lot more to it than that. Even in name, the form "memoir" speaks of memory itself. So of course, in the natural writer-grouping portion of my mind, I began to think about other UK literary writers who have written novels that are arguably science fiction. Well, duh, Kazuo Ishiguro. When I had interviewed him, he and I talked some time about the transformative power of memory as a writing tool. My take, was to stretch what Ishiguro said just a bit so that it sounded a bit like genre fiction. That is, to my mind, once you the process of remembering creatively, you've really entered the world of fantasy. This is course, taking us back to the meaning of fantasy as it refers to say daydreams and wishes more than unicorns and elves. The world of the memory fabulists, as I'll call them, is actually more surreal than the world of Tolkien rip-offs. The latter really trend towards a sort of gritty medieval adventure format. Sure you might get some unreal elements, but the focus is on the down and dirty, not on the odd and transformative nature of vision itself. And Mitchell operates in the latter mode, using memory as a way of re-creating the world from whole cloth as seen by a thirteen-year old boy living in, "the sleepiest village in muddiest Worcestershire in a dying Cold War England, 1982." This time, Mitchell is abandoning many of his usual narrative techniques -- the disembodied narrator, the splintered-and-re-assembled chronology, the speculative visions of the past, present and future -- or at least, he's re-tooled these to tell the narrow, focused story of Jason Taylor. 'Black Swan Green' takes a one-year slice of Jason's life and lets us live it as Jason sees is, or rather as Mitchell writes it. Let me tell you, flat out: Mitchell can write like nobody's business. Writing-wise, 'Back Swan Green' is the equivalent of seeing a tri-athlete do twenty perfect push-ups. And I mean picture-perfect. There are a certain class of novels that reveal and revel in the stuff of life, novels that just seem bursting with the kind of people, places and actions that are not necessarily grand, not necessarily the great, but rather, just ordinary people seen in such clear focus that the vision is revelatory. Read the first page of this novel, or read, for example, Julian Barnes' 'Arthur & George' and you'll get an idea of what I'm talking about. Phil Rickman's Merrily Watkins mysteries ('Smile of a Ghost') have this effect, as do the novels of Jeffrey Ford, for example, 'The Girl in the Glass'. In 'Timothy; Or, Notes From An Abject Reptile', Verlyn Klinkenborg writes from the point of view of a turtle. How can that not be fantastic? Tahir Shah does this as well, in 'Sorcerer's Apprentice' and his more recent work, 'The Caliph's House'. Mitchell and others are fantasizing a new view of the real world. You know how startlingly clear some of the latest cinematography seems, especially when it regards some scene of action? You can see the crystal-clear edges of the car as it flips through the air, of the sword as it swings? This is the prose equivalent, aimed at real life, at everyday events, as focused through the eyes of a thirteen-year old boy. Those eyes don’t see exactly what's there, as least not as adults see it. Those eyes don’t think, don’t know that they're transforming their own vision of the world. But David Mitchell sure as hell does. David Mitchell is a prose cinematographer of startling clarity, of shimmering vision. 'Black Swan Green' uses memory to create a world that is not necessarily the real world, though the world is written with the kind of precision that makes it seem utterly real. This is the "real world" of a thirteen-year old boy. Those of us who are past that age, who have passed through those years, probably can't quite put together how it felt, how it looks anymore. Mitchell's here to do that for us, to remind us that the world we now occupy, the vision of the world that we now hold is not so certain as that of our youth. And he's also written a novel that's quite a bit more accessible than perhaps his other novels, as a result. I can't say that this is exactly the stuff of bestsellers. Mitchell's work is a bit too fine for that easy-come, easy-go style of reading. 'Black Swan Green' is a sticky novel, in that it sticks with you, gets under your skin. Mitchell's vision infects the reader's vision. His re-invention of the world, his fantasy of the real world infects our vision of the real world. Still, damn , the man can really write, he can fill up a book with so much life that yours might just go away for those few blissful minutes of reading. But it's no longer 1982, and you're not thirteen years old any more. That's a fantasy, my reading friends. Immerse yourself, re-invent your vision. Pretend. |

|

02-14-06: Simon R. Green is 'Sharper Than a Serpent's Tooth' |

|||

Keeping

Up With the Nightside

But then, it totally escapes me as to why these John Taylor novels get the quick MMPB shuffle and the DeathStalker novels, which seem much less interesting to me, pop out in hardcover. Heck, I even like the cover art by Jonathan Barkat. And my wife will attest as to the pile of books that I drag around. It's not easy to keep these little guys together, but somehow I manage. Even if I did have a panic attack the other day, that found me searching through the stacks for the first book, which I have two copies of. Well, I found one of them, so that's all good, right? And I did so just as I got the latest John Taylor adventure 'Sharper Than A Serpent's Tooth' (Ace / Berkley / Penguin Putnam ; February 28, 2006 ; $6.99). There are lots of things to like about these books. For one thing, they have an overall story arc that's moving forward pretty quickly. The deal is that John Taylor, the PI for the Nightside, has a mother who might just bring about dat ol' Poccalypse. Damn! Something of a problem for John, who just wants to sip whiskey in his office until the next blonde shows up. But it's something he's got to deal with, and in this, the sixth novel in the series, it looks like things are going to get serious. Mom's here, John's here, and everything is set to blow all to pieces. I'm guessing the babe walking on a sea of skulls we see on the cover is rather relevant to the action that transpires inside. Lots of our favorite characters are back as well -- Susie Shooter and Dead Boy and the Speaking Gun. You have got to love a series that features a speaking gun. But mostly what keeps these books going for me is Green's prose, which combines just the right levels of hokey-jokey and hard-boiled attitude. And even when Green is going to bring an end to everything, he doesn't get all meaningful on you. He knows that these books are light amusement, a series of great scenes that go down faster than you think, concealing a skill you would not expect to find. Also worth mentioning is the blistering pace at which these books are released. Yes, they're all pretty short. This one tops out at 247 quick-reading pages. But still, to be on book six of a series when the first one came out less than three years ago, well, that's got to be some sort of record. To my mind, it's a great record. There's not a lot of waiting about in Simon R. Green's Nightside. It's monsters, foes, and lots of woes. Yes, I love a challenging, thought-provoking novel. But sometimes, it doesn't pay to provoke my thoughts. And more often, I'm willing to pay just to prevent thoughts from coming into my brain. To a certain extent, that is one of the main functions of reading. Prevent rational thought now! |

|

02-13-06: Max Yergan: Race Man, Internationalist, Cold Warrior; Talking Trash |

|||

David Anthony III Traces The Unseen Corners of Early 20th Century Black History

The upshot is that I get exposed to a much wider variety of books than I might otherwise default to seeing, which is why I court all these opportunities. I love stumbling across these odd-to-me titles that are entirely outside genre fiction, entirely outside the average experience of even the usual book-writing world. Not all of them pan out, of course, usually because of time constraints. But the stumble-effect, as I suppose I should call it, keeps me fresh, and just damn-well opens up my otherwise myopic vision. But even by my stumbling standards, I was lucky to come across 'Max Yergan: Race Man, Internationalist, Cold Warrior' (New York University Press ; January 1, 2006 ; $49.00) by David Henry Anthony III. Eventually, I suppose, I would have heard about it via Capitola Book Café, where he's appearing in March, but in this case, I actually heard about it via a mutual friend of the author, who is a Professor of History up at UCSC. He told me a bit about the book, enough to pique my interest, and it showed up a few days later, after I'd forgotten the publisher, in a peculiar-looking package. "New York Press?" I thought. "What the heck is this?" It happens to a fascinating look at a corner of the world, at a time, at places, people and ideas I had no idea ever existed. It's strange how history can seem so fantastic, how our world can house so many foreign ideas and people we've not heard boo about. And our strange world certainly brought us Max Yergan, whose journey is utterly different than anything you might expect, whose life and story arc are almost beyond any fantasy or political imagination you might have applied. There's no explanation or expectation that properly applies to Max Yergan. You just have to read his story and think: "This old world, she's stranger than we can imagine, no?" I'm going to try to start at the beginning and give at least some idea as to what Max Yergan, and thus this book is about. Try to wrap your brain around it. You won’t be able to, trust me. No executive summary does this man justice. Max Yergan was born in 1892, the grandson of a carpenter born into slavery. He was born and raised in Raleigh, North Carolina, into a world where genteel pretensions of tolerance went hand-in-hand with brutal lynchings. He ended up in Shaw University and the Black YMCA at a time when it encouraged Christian activism to end exploitation. And from there, he went to India, in 1916. Can you imagine this? I couldn't, and wouldn’t have thought to. Yet this is precisely why we read. But wait, it gets stranger, and there's much, much more to Max Yergan's life. Yergan traveled extensively, in WWI, and afterwards. He ended up in South Africa, where his exposure to the brutal regime then in power radicalized him, to the point where he joined the Communist Party in the mid 1930's. But in less than ten years, the nascent hysteria of the Cold War drove him in the other direction, and he became an ardent conservative. The rest of Yergan's journey frankly beggars the imagination, which, again is the reason to read this fascinating work. David Anthony has done the work of creating a world, of tracing a time and a life and a place through a series of changes that I think most readers today would find beyond far-fetched. To me, Yergan's life verges on incomprehensible, almost fantastic, and Anthony's re-creation of Yergan's story is the kind of thing you just couldn't make up. He gets all the details right, and he writes a cohesive and coherent story of a century and a life that was tearing itself apart, torn in so many directions by forces still at work today, still ripping it up in this very moment. Reading 'Max Yergan' is like looking at early pictures of a hurricane-to-be. The clouds are there, the wild winds, the dark storms forming. You've experienced the devastation, but not the birth of those winds. You can only see the maps from above; Anthony takes you below the cloud cover. I won’t tell you what happened in Max Yergan's life. It's pretty much beyond my ability to suss. But I can tell you this: it's worth reading about. It's a time and a place that no longer exist, yet a time and place that formed this time and place. We can never get there, except in books, that, readers is the whole damn point of reading. |

|||

A Conversation with Heather Rogers

Heather's take on trash is really interesting. She has a rather Marxist, economic interpretation of this more-recent-than-you-think phenomenon. But she's really clear in her explanations of why we have so much trash and the socio-economic circumstances that brought our present trash economy into being. She also knows all about the technology of trash. This is the first and perhaps the best explanation you're ever going to hear of how a landfill works, does not work and how long we can expect it to do the former before it starts doing the latter. Those of you using the podcast link have already downloaded this. If you’re lucky, you'll get a chance to hear Heather in person; and if you have that chance, by all means, do so. She's a great speaker. If not, then here are links to the MP3 and RealAudio versions of this interview. Don’t throw this chance away! |