|

|

|

This Just In...News from the Agony Column

|

04-07-06: Alex Berenson Unmasks 'The Faithful Spy' |

|||

Worst-Case-Scenarios

R US

We're in a similar situation now, only that end has not yet come to pass. So when someone writes an ultra-topical spy novel, the publishers had better get it out pronto to ensure that it's not outmoded by some horrific or happy current event. (This presumes that one perceives an event such as the "fall" of the Soviet Union to be happy, a debate I'm not going to undertake here.) Topical fiction is the hardest thing to write, because, as Josh Spanogle, author of 'Isolation Ward' told us in his interview, even a few months can invalidate the very premises upon which your plot may turn. And the wait between writing a novel and having it published is torturously long. Alex Berenson is one of the lucky ones. His new novel 'The Faithful Spy' (Random House ; April 25, 2006 ; $24.95) is certainly of the "ripped from the headlines" variety. The twist here is that Berenson himself used to write some of those headlines. That lends what he proposes in this ultra-modern take on the horror novel a greater cachet than your average, garden-variety doomsayer. Berenson is not a green room general, blithely suggesting strategy while someone ensures his nose is not shining. Berenson has a closet full of shoes that the talking heads of these interesting times would do well to walk in. In two tours covering TWOT in Iraq for the Grey Lady, Berenson saw the effects of our long-term and long distance planning from the ground. In Iraq, he was held captive by a Shia mob, mortared while in a 1,000-year old cemetery and generally battered about more like a real human being than a chess-piece on a shiny situation table. Presumably, he came away a rather different person than the reporter who arrived. More importantly, he came away early enough with enough background material and gumption to, and here I quote, "go beyond journalism" (DANGER WILL ROBINSON!). In my experience, what lies beyond journalism is, uh, fiction. In this case, gripping and super-informed fiction, and what I suspect might well be, to quote Stephen King, "the future of horror". Horror fiction is what scares us, right? And as gross and unpleasant as say, a plague of zombies may be, I think most of us would greet such a plague with a sigh of relief. After all, even if they run fast, everybody knows that you just shoot the guy with a ring of blood around his mouth in the head. End of story, more importantly, end of worries and even more importantly, beginning of story-rights sale. Berenson, on the other hand is busy writing about what really scares the bejeebers out of us 'Murricans these days, if one is disposed to believe the ever-reported-about opinion polls. Domestic terrorism. 'The Faithful Spy' unfolds as John Wells, a CIA agent who in 1997 manages to get himself hooked up with a then-upstart outfit known as al Qaeda, finds himself some seven years later (2004, for the math challenged) having bought into the beliefs he was originally assigned to spy upon. He's become a devout Muslim who doubts the American agenda, even as he is sent to America to launch the sequel to 9/11. Berenson's novel cannot avoid the giant clichés that loom before it like NY skyscrapers. But Berenson has what just about everyone else who opines on this topic lacks, that is, actual experience on the ground amongst the folks holding guns and wearing targets. 'The Faithful Spy' allows him to expertly scare the living heck out of readers with monsters that, while they are susceptible to bullets just like zombies, prove to be much smarter, faster and far more intractable. I say, bring on the zombies! I'm not sure I want to reach the levels of fear that 'The Faithful Spy' is clearly capable of inspiring. This is after all, the War On Terror. What the heck are we doing terrorizing ourselves? That is ever the question that one asks horror writers. Steve Aylett, via SF writer Jeff Lint, suggests that when one gazes into the abyss and the abyss gazes back -- bill it! Berenson, on the other hand, wants us to understand it. That's not a bad idea, and "going beyond journalism" is probably the best way for us to achieve that goal. Talking heads tend to favor loafers that generally never even walk a mile. Berenson has been there and seen the abyss close-up. He's probably got the abyss doing its own version of a talking head on tape. This suggests that his ultra-topical horror fiction has the ring of truth, even if said truth is ringing amidst the skyscraping conventions of espionage fiction. Like every genre, espionage fiction has its literary giants. Berenson at least brings some knowledge to the table, even if his premise makes you want to hide under the table. And this, of course, is what interests me. 'The Faithful Spy' has all the appurtenances of espionage fiction. The conflicting loyalties, the layers of deception and self-deception, the lies that become the truth even as someone hits the truth-turns-to-fiction button. Meetings with foreign powers. Meetings with those of the opposite sex and perhaps allegiances as well. Yes, it's all here, even the title, which suggests the faith-based world in which we're told we now live. But what's the upshot of all the setup? Is it to offer a look at the life of spies, or is it rather to simply frighten the reader with the possibility that body snatchers may live among us? That depends as much or more on the reader than it does on any intention the author may have brought to the work. What we have before us are the words, the glorious words. We can read them and fear. Read them and weep. Read them and learn. Or all three. Berenson clearly does have something to say, and he's been places most of us will never go, or even really, want to go. Those places, the places we don’t want to go, the places we fear to go -- what emotion keeps us away? Horror or ignorance? Understanding the difference, if there is one, is the best one could hope for as the result of reading a novel that "goes beyond journalism." |

|

04-06-06: Alison Bechdel's 'Fun Home' |

||||||

American

Memoirs

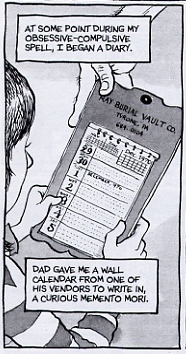

Of course, all this controversy has the effect of selling even more books. Don't count the memoir down and out yet. Damn, we're a nation of rubberneckers, aren't we? Give us a good ol' car wreck on the side of the road, we just can't help slowing down. I don’t know about you, but I remember driving around with my parents to take a look-see when we heard fire-trucks in the neighborhood. Alas, when I heard the fire-trucks in my neighborhood, no driving was required -- it was the house two doors down that was on fire. Into this world of memories true and false, fabricated and real, remembered and, shall we say, mis-remembered, comes Alison Bechdel. She's a comic artist primarily known for her strip Dykes to Watch Out For, syndicated in fifty newspapers. Like most of us, she had a childhood she found interesting; unlike most of us, her childhood actually was interesting. No simple rubbernecking for Alison, no sirree. Her story was...complicated. Complicated enough that it eluded her when she first tried to tell that story in prose, in her twenties. Now, of course, she's done some growing up and got some helpful distance. It's the kind of distance that helps put the complications in a perspective where they can unravel, where they can wrap back round on themselves, so that Bechdel can find the stories within the stories. She's also got years of storytelling experience as a comic artist. Now in her [mumble mumble]-somethings, Bechdel is able to tell her story in the medium she's come to know so well. The upshot is that you can get a gander at life in Alison Bechdel's 'Fun Home' (Houghton Mifflin ; June 8, 2006 ; $19.95) should you wish to rubberneck in the comfort of your own fun home. Rubbernecking is what this whole memoir craze is about. Our fascination with the ways that other people wreck or live their lives offers us a little cold comfort as we compare them with the ways we've wrecked or lived our lives. Moreover, in a literary sense, these books offer us the bread and butter of the best fiction, in that they often present us with vividly realized and pretty realistic characters. So don’t count the American Romance with Memoirs over yet. Instead, you can tuck into Bechdel's take on the genre and plunge your mind into her world and in this book -- her father's world. 'Fun Home' is, not surprisingly, a pretty odd affair and not just because Bechdel had a pretty odd childhood. But that helps, or, at least, it surely adds rubbernecking value. The executive summary reads like this: As a child, Bechdel grew up in the "Fun Home" which is what the family called the funeral parlor her father ran when he wasn't teaching English. Bechdel's father was the lynchpin of her childhood years. He was a historic preservation expert who kept their house filled with Victorian finery, imagining himself to be a sort of aristocrat. (When he wasn't sewing up corpses.) He was a closeted homosexual, who had affairs with his students. As Bechdel herself came out, he died, or perhaps he committed suicide. OK, time to take a breath. Feeling better? Well, you might if you manage to wrap your brain around Bechdel's rather intense memoir. She's pretty direct when it comes to the question as to whether or not it's all true. "I frequently question the reliability of my own narration," she says. "I really don’t know whether my dad killed himself or what he did with those teenage boys." Curiouser and curiouser, no? "I think that's a good model for memoir writing: acknowledging the inadequacy of your own methodology."

What stands out more than anything is Bechdel's particular and peculiar storytelling style. The story unfolds not chronologically but almost fractally. Stories within stories and revisions of the same story present similar events again and again with new perspectives. She refers to the style as recursive. It's an interesting way to tell your own story, especially in light of her comments about the composition of the memoir. And this, in the end, is what got me hooked into the story that Bechdel tells in 'Fun Home'. Strip away everything else and you've got a fascinating writing style. Bechdel tried to tell this story in prose but backed off and threw herself into Dykes to Watch Out For. Now she's come back to it, and she's brought not just a new style but a new range of skills to her storytelling. Her 'Fun Home' may not have been much fun at the time. And in truth, the story she tells is not itself lots of fun. It does however offer lots of life. But for readers, offered the chance to step into her multi-layered world, the joy of experiencing a strong story told well and in an original manner -- that's always fun. This is why we read, to experience in that direct fashion, lives outside our own. To illuminate our own lives, from within. |

|

04-05-06: Vernor Vinge Reaches 'Rainbows End' |

|||

Before

the Zones of Thought

That's because much of Vinge's work of late has been set in the far future and on the farthest frontiers not just of space, but of mind. Vinge is one of the biggest movers and shakers of that all-encompassing subgenre of science fiction known as Singularity fiction. His bread and butter is by-definition beyond-incomprehensible. One might well suspect the future sent him back here to teach us all some lessons, and with award-winning classics like 'The Peace War' and 'A Deepness in the Sky', he's doing one hell of a job. So, yes, it does come as a bit of a surprise when he pops out this toe-tapping tale of tension and terror with only one foot in the future. For about thirty seconds, then you know, you just get over that surprise because Vinge has also made a career of surprising readers. We're reading science fiction because we enjoy the sense of wonder and the shock of the new. In fact, we don’t just enjoy them, we're all rather addicted. Here's our latest fix, and slavering addicts that we are, we'll not ask too many questions. This time around Vinge has set his sight on problems occurring in the very near term. Starting in San Diego in 2025, 'Rainbow's End' unfolds through the eyes of a recovering Alzheimer's patient, Robert Gu, and his family. Readers looking for connections to Vinge's other work need not look far. Gu attended Fairmont High; now -- as in 2025 -- he's getting sucked into the sort of sinister conspiracy we all imagine is being hatched at the moment in corporations and military installations. You know, the old Rule the World deal. Vinge is of course the kind of visionary who can pull this sort of stuff off in his sleep, but he's bug-eyed wide awake here, and ready to scare his readers into a similar state. From the opening disease vector to subversively oppressive high-tech shenanigans, Vinge knows precisely how to suck readers out of their world and into his. Vinge's start point is several magnitudes beyond our own post-shock world. Bio-terrorist attacks have subsided by 2025, but that's sort of like saying that World War II had subsided by 1955. We all felt safe back then, didn't we? So long as we had a fallout shelter in our back yard. The real problem is the spread of low-cost, relatively low-tech mass-death technology. Vinge's world might seem safe and secure, but at least some of the characters know that, "such optimism was dead wrong." And the real real problem is, alas, that Vinge's near future is pretty much our present. Or at least the result of our present to the future. Once the toe-tapping starts, prepare for a blast of short chapters and lots of action, both physical and mental. Now, I have to love a book where the characters end up shouting, "We want our REAL books!" This novel qualifies. But it could also herald big things for Vinge and for the genre as a whole. Bring this one up on *.* through a search for the author, and in the list of titles, you'll see this pegged as a "Zones of Thought" book. That suggests that it functions as a sort of prequel to Vinge's biggest works, where Vinge has been burrowing backwards for quite some time now. First we had the cyber space opera 'A Fire Upon the Deep', and then 'A Deepness in the Sky', which scooted back some 30,000 years. Lest readers think they're getting the usual gooey science fiction, let me hasten to explain. Vinge is a mathematician, and yes, you'll find the "Portions of this novel previously published" message on the colophon page. But it's not Asimov's, F&SF, or even Analog where this story first saw light. Nope, it first ran in the august journal IEEE Spectrum, which is quite likely to talk about circuits and patent laws and utterly unlikely to talk about spaceships and aliens. This is yet another suggestion that 'Rainbows End' is operating from a firm base within a world that most readers actually inhabit. And that is the means to reach a lot of readers. With 'Rainbows End', we're all the way back into what I'd call post-present fiction. 'Rainbows End' is super, ultra readable yet it preserves the sort of mind-boggling effects that we know and love both in SF and Vinge. With its next-gen terrorism background and the combination of corporate greed, infectious disease and computer viruses, it is very accessible to a mainstream audience. Tor is going to pop for advertising in the NYT Book Review. Here's the near future publishing scenario that Tor -- as well as science fiction readers -- might hope to unfurl. 'Rainbows End' gets mainstream notice, mainstream attention and even sneaks into a few bestseller lists. Suddenly, general fiction readers are looking at Vinge's latest and asking the question that is literally music to Tor's ears: "Is that all there is?" No as it happens, it's not all there is. Readers will have been seduced into picking up what is within its own chronology the first book in Vinge's "Zones of Thought" series. Imagine if mainstream readers managed to pick up 'A Deepness in the Sky' and 'A Fire Upon the Deep'. We've been immersed in enough fifteenth-rate shoddily thought-out movie space operas over the last thirty years that it's not inconceivable this could happen. And given that turning point in my alternate future publishing history, we could be on the verge of a mass discovery of the current treasure trove of Space Opera, the stuff that deserves the capital letters. And all this because Vinge rolled back in time to this post-present setting. Yes, I know it involves a lot of wishful thinking, and we're a lot better at wishing than thinking. Conjoining the two is of course ill-advised. But Vinge's got the real deal here. Thrumming suspense and thrilling wonder story ideas. The book is titled 'Rainbows End' fercrissakes. I'm going to indulge. Now is the perfect time to travel back along Vinge's timeline into a post-present more troubled than our present. Maybe it's a bit of a bad idea to hope the future will get worse because the present is so bad. It's all about tipping points. Are we about to really embrace science fiction, real science fiction by scientists and artists like Vinge? That's a prediction I'd like to see come to pass, no matter what the background holds. |

|

04-04-06: Daniel Abraham Is Under 'A Shadow in Summer' |

|||

The

Long Price of the City

That's why we're seeing the sort of fantasy exemplified by Daniel Abraham's 'A Shadow in Summer' (Tor / Tom Doherty Books; March 7, 2006; $24.95), the sort of fantasy in which labyrinthine conspiracies unfold in crowded cities. The sort of fantasy where technology, of a sort, provides the kind of plot point you'd expect to find in science fiction. The sort of fantasy where the quirky social moirés of our world are lifted from their jewel-like settings and placed in new settings, so that they may once again shine for us. Abraham's novel is nothing if not complex. The setting here is the city-state of Saraykeht; think of Singapore, Hong Kong, New York and Hollywood, run by djinni and fueled by a faith in something more technological than gods and more theological than genengineering. You get the idea; we've seen this sort of thing done before, so there's no revolution. But Abraham brings his own vision to table. Saraykeht is the jewel in the crown, the Ptolemaic center of Abraham's universe. It has conquered with commerce. Threaten the trade base and the rest of the house of cards crumbles. And you can threaten the trade base if you can disrupt the tech at the heart of the city, the captive spirit Seedless and his minder-master Heshai. Or you can at least make life very uncomfortable for the Powers That Be, and that may be enough for the forces gathering at the gates. Works like Abraham's novel, the first in a quartet, reflect our interest in wallowing in the things that frighten us most. In Saraykeht, you have the clash of the cultures, our economic insecurities, our constant concerns about a civilization based on technology that isn’t easy to understand and seems frighteningly limited and even our social anxieties remixed with a soupcon of the surreal. It's our world made worse and better. Worse by virtue of the horrors coming right out to play, better by virtue of the potentials for salvation coming right out to fight. If we're to confront our fears, we're at least allowed to play to our passions. And the fact of the matter is that most of the fantasy reading audience lives near enough or has enough experience of the Big City that it's just natural we'd expect to find the problems and the solutions concentrated there. Even when we're reading to escape the Big City we find ourselves dreaming about it. It's a closed loop. The more we try to escape, the more we return. Abraham has a lot going for him. Stephan Martinere provides the classically beautiful and complex cover to suggest what waits within. Even better for Abraham, George R. R. Martin, who publishes for Tor competitor Bantam / Spectra, offers Abraham a compelling cover blurb, which will probably sell more copies of this book than all the reviews in Araby. And finally, there's the book itself, an alluringly short 331 pages. Of course, we've all see serial bloat in fantasy series. The first book looks short and sweet, but by the time you get round to book four, you're sporting a wheelbarrow. But at least Abraham doesn't start out with a BMI (Bloat Mass Index) that screams of subplots gone crazy. I'll take that as a good sign. So, yes, the signs are auspicious for Daniel Abraham's first fantasy series. But what bodes best here is the work itself, the fact of the matter, the seed that starts the series; that is, Abraham's ability to use the genre to see beyond the confines of our world and back into his own world. Paradoxically, we need to escape from our world to see it most clearly. |

|

04-03-06: David Sirota's 'Hostile Takeover'; A 2006 Conversation With Verlyn Klinkenborg |

|||

Pericalypse

Now

David Sirota believes that the end has come to pass as well. Not to put too fine a point on it, he's mad as hell and is not going to take it anymore. 'Hostile Takeover' (Crown / Random House ; May 2, 2006 ; $24) teeters between white-hot anger and pitch black humor. The author states that "This book is not for those who see politics only as another kind of infotainment or reality TV show." But that doesn't mean that his book can't be entertaining, does it? Because, believe me, Sirota writes at the kind of fever pitch that makes no friends and takes no prisoners. I have to admit that I was laughing out loud seconds after opening up this book. The problem is that the laughter is neither with nor at Sirota. Your laughter will be directed at the absurdity of the situations that Sirota describes. This whole pericalypse -- it's not as great as it sounds. Sirota's observations are bluntly, painfully honest. Yet there's enough of a veneer of hope embedded within 'Hostile Takeover' that of the two potential reactions -- laughter or tears -- laughter comes to mind first. Any way you slice it, 'Hostile Takeover' is funny -- painfully funny. You have to laugh. The alternative is... Doing his part to prevent Lem's Pericalypse and to make book sites like mine totally unnecessary, Sirota tells us from the get-go "Who Is This Book For?" and "Who is this book not for?". Really, those are first two sections following hot on the heels of the opening salvo. Yes, it is an opening salvo, a no-holds-barred diatribe against the corporate culture that Sirota sees as having bought the US government. That, of course, is the same corporate culture that is publishing this very knife that longs to cut its throat. And he's got compelling stories to back up his assertions. We are cursed to live in interesting times, aren't we? Sirota contends that his book is for those that Harlan Ellison once called "The Great Unwashed," the silent majority who are being unsilently screwed by the moneyed minority. He suggests that those of all parties and affiliations will find something to love or hate in his treatise about how business has bought government. He's certainly got my attention. The society that Sirota describes is like something out of 'Neuromancer', or -- and he makes this comparison explicitly -- 'A Clockwork Orange'. In fact, it's pretty interesting to contemplate how so many politically-oriented works are finding it necessary to use works of science fiction and even fantasy as referents to describe what the heck is happening to our sad world. Sirota starts out with Burgess ('A Clockwork Orange') and quickly gets his readers into 'The Matrix'. If you choose the red pill, you head into the book and find out the devils in the details that Sirota unearths. Sirota's book covers a variety of subjects -- Taxes, Wages, Jobs, Debt, Pensions, Health Care, Prescription Drugs, Energy, Unions and Legal Rights. For each chapter, he discusses lies, myths and misperceptions, then offers up some solutions to the problems he identifies. And that Matrix analogy? It lasts right through to the end of the book, when in his conclusion, Sirota says: "If you've made it to this point, you decided to take the red pill." Apparently, Kim Stanley Robinson was right when he suggested that we are living in a sort of bad science fiction movie. But that again brings back the question of books, too many books. Here we have a production machine gone crazy, a monster producing offspring without regard to quality. The same publisher that offers 'Hostile Takeover' offers mountains of pabulum. And if this monolith is part of the corporate world that has engineered a 'Hostile Takeover', is it possible that it has grown so large, so unaware of its own ability to produce, that it has managed to manufacture the pill that will poison it? 'Hostile Takeover' aims to be that pill, that poison. Can it succeed, or has it by definition, as the product of the machine, already failed? Sirota offers hope. Some. But mostly what he offers is great writing, the kind of incendiary invective that makes you want to read it aloud to your spouse. Let their eyes roll as you read. You've taken the bitter red pill. What do you see? I see a bad science fiction novel, written in the 1970's. It's my life, it's your life. If I'm going to have to endure life in a bad science fiction novel, can't I at least get some cool monster action going? Oh wait -- I'm in the monster's stomach, being digested. Maybe that monster action proves to not be as cool as I anticipated. |

|||

Timothy

Speaks

The Natural History of Selborne, by Gilbert White, with the journals of Gilbert White, are the source materials for Klinkenborg's wonderful exploration of nature, humanity, landscape and how they all tie together. We talked extensively about bird watching, gardening, and how Klinkenborg uses fantastic fiction to explore the world. Lots of writers are, or have been teachers, and Klinkenborg is no exception. It comes across in our conversation, and anyone who has ever put pen to paper or fingertips to a keyboard will find Klinkenborg a genial, entertaining and very thought-provoking speaker. Should you get a chance, make sure you see him in one of his appearances. As a bonus, for this week's Podcast, I obtained a five minute reading by the author from 'Timothy; Or, Notes of An Abject Reptile'. (MP3 and RealAudio.) It's powerful and beautiful. Moreover, Timothy is smarter than most people you'll meet. He's a bit laconic, and one of the things that Klinkenborg talks about is the fascinating process he went through to create this gorgeous prose. When Timothy -- or his speechwriter -- speaks -- you'll want to listen. |