|

|

|

This Just In...News from the Agony Column

|

07-28-06: What Price Fantasy? |

|||

Six

Bucks, 88 Pages

So will Fantasy Magazine stick? It deserves to, but then, most of them to my mind deserve to stick. Any magazine is a mixed bag. Face it; you're not going to like every story in every issue. But that's to a certain extent why one subscribes to magazines, to help discover authors one might want to pursue and authors one might want to avoid. Magazines aid these quests in two ways. Most obviously, by publishing short fiction by writers so that you can read something and say; "Hey, more!" or "Hey, er – not for me!" But then perhaps equally obviously, magazines offer reviews and interviews that help readers get a bead on authors, again to sort them into the More and Not For Me camps. Fantasy Magazine issue number two is certainly worth your time and your money. I could live without the hotcha cover, but at least it's only mildly embarrassing. It's what's inside that counts. Fantasy is a solidly produced magazine with a similar look and feel to Cemetery Dance. That means a slick cover and what I'd call "quality newsprint" pages. The art gets no credits and looks to be clipped from public domain masterpieces. It's pretty effective, and at least it's not distractingly bad. But the bottom line here is that you're paying six bucks for fiction, an interview and book reviews. I think it's certainly well worth the money, but this is certainly not girls-in-fluffy-dresses fantasy. In fact, Fantasy Magazine reads quite a bit like Cemetery Dance Magazine, albeit with a rather different set of authors. Were this to be the 1980's, it might be called Horror Magazine, but here in the de-lightened 21st century we're calling it fantasy. Just don’t expect to find any damn dwarves, elves or mages on quests, and be glad, oh so glad that you won't. Fantasy Magazine is weird fiction, plenty of it, a wide spectrum by, in this issue, a few authors you're probably familiar with and more that you aren't. Familiar names include that incredibly talented Stewart O'Nan. His story, "The Novel of the Holocaust" is pretty indescribable, but let's call it a remarkably engaging piece of metafiction that is both darkly humorous and deeply disturbing. Read the first line at your own risk, but not just before you intend to do something, as you won’t stop until you see Stewart O'Nan's smiling face. One of the nice touches for Fantasy is that it offers readers a decent-sized thumbnail photo of each author at the end of the story. Editor Sean Wallace makes a lot of smart choices here, offering stories that are pretty short and quick, one-sitting reads. Caitlin R. Kiernan's "Madonna Littoralis" is a harrowing tale that turns on a bit of Fortean lore, a second person tour-de-force about personal transformations. Theordora Goss is effectively interviewed by Matthew Cheney, and offers a historical ghost story "Lessons With Miss Gray". Between the two of them, the effect is to send you swiftly towards the also-published-by-Prime Goss collection, 'In the Forest of Forgetting'. Not a bad (or new) idea to use a magazine to publicize authors also being published by a small press. Paula Guran edits a slew of book reviews that map the same territory covered by the fiction; some that might fall under the banner of fantasy, and some that might fall under the banner of horror. One of the things I find interesting about these reviews and reviews in general is how a good review can warn a reader off a book or a bad review can draw a reader to a book. In this case, while the reviewer finds Christopher Golden's 'The Shell Collector' lacking, the review practically unloads the money from my wallet. But this is only reflective of my own peculiar prejudices. How could I not love a novella about a lobster monster? But since the reviews come from a variety of reviewers and are not individually credited, it's hard to draw a bead or set up a model for comparison. I hope future issues will individually credit the reviews. So, Fantasy Magazine, Issue two, six, bucks, 88 pages. Will we be writing about this in some fifteen or twenty years? It would be nice wouldn't it, were the world to prove friendly to such an endeavor. The world is rarely nice to anyone or any endeavor. Fantasy will have to fight to survive. It's looking good though. Hotcha. Get it while you can. |

|

07-27-06: George Pelecanos Pursues 'The Night Gardner' |

|||

Planting

the Seeds of Revenge

His newest novel, 'The Night Gardner' (Hachette Book Group / Little Brown ; August 8, 2006 ; $24.99) is, like 'Drama City', another standalone work that combines crime fiction and character studies in a detailed social context. Pelecanos manages to create tension-filled plots that propel the reader into situations that render the social causes and costs of crime with stark clarity, by revealing his carefully created characters. It gives his novels a literary feel that makes them extremely satisfying to read. 'The Night Gardner' runs from a classic crime fiction premise, one we've seen played out to great advantage by writers like Dennis Lehane and Michael Connelly; the old unsolved crime that comes back to haunt a career cop. In 'The Night Gardner', the career cop is Gus Ramone, a twenty-plus year veteran on the DC force working the homicide unit in the violent crimes division. Back in the day, he, Dan Holiday and senior detective TC Cook searched for but never found the Night Gardner, a killer who left bodies buried in parks. In the years since, Holiday has left the force after a morals charge, and has hit the skids. Cook has retired but never stopped worrying at the case. When a friend of Gus Ramone's teenaged son is found buried in a park, Ramone begins to think that the Night Gardner is back at work. He tries to "solve" the crime, with the help of the two men who once worked with him on the Night Gardner case. Complications ensue. 'The Night Gardner' looks to me to be the most literary of Pelecanos' oeuvre yet, a layered and complicated character study wrapped around two potentially connected crimes. That said, there's no doubt that Pelecanos preserves his rather austere presentation. There's a simplicity and a clarity that is apparent on any page you might choose to read. Pelecanos does not play any literary prose games. His prose is not textured. In fact, I'd describe it as denatured, scrubbed, dipped in rubbing alcohol and set afire, leaving behind only the steel skeleton. This allows Pelecanos to examine emotionally and socially charged situations without seeming bathetic or overblown. There's a "Just the facts, ma'am," feeling to what he writes. The upshot of Pelecanos' dry approach is that the emotions and social milieus he does examine seem utterly real, and very powerful. I guess what I'm getting after here is that Pelecanos never pre-judges for the reader. He lets the reader decide what the reader thinks of these characters and he's both aware of and happy that different readers might feel very differently about both the characters and the choices they make. Pelecanos isn’t all that interested in presenting crime fiction as a puzzle story. If that's your interest in crime fiction, then Pelecanos might not be your best choice. In fact, like some Ruth Rendell novels, Pelecanos' work tends to suggest that crimes are neither solved nor resolved. Crime happens because characters make decisions they are compelled or convinced to make and the repercussions are always unexpected. In fact, to a certain extent, Pelecanos might be said to re-define crime. In his novels, a crime might be best defined as a choice that has horrendous consequences that are not foreseen by those making the choice. Sometimes that choice is within the law, and often it involves leaving the law behind. There's no resolution, really. There's just dealing with life afterwards, generally not a pretty picture. Conversely, this makes Pelcanos' novels quite beautiful in their own austere fashion. One is reminded of the work of Emile Zola, or even Charles Dickens, of writers who simply said to themselves: Just look around. |

|

07-26-06: Chris Adrian Floats 'The Children's Hospital' |

|||||

Angels

and Seven Miles of Water

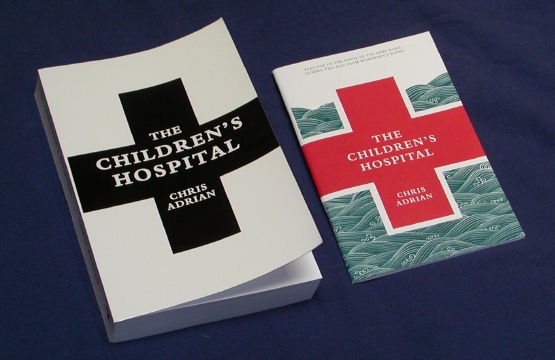

The landscape of speculative fiction is being changed, one book at a time. McSweeney's is just one agent of this change, and 'The Children's Hospital' (McSweeney's ; October 2006 ; $24) is just one book in the landscape. But it's a pretty unusual and compelling vision, a combination of everyday grot and unearthly delight, of quotidian medical horror and apocalyptic destruction. Chris Adrian does not mess about. He goes for the throat, then the next throat, and then the whole shebang. Underwater. Under seven miles of water. And one lesson you'll learn right off the bat; don’t fuck an angel. Sorry to be crude, but you know, duty calls, I answer, and answering, as it were, involves more listening than talking. 'The Children's Hospital' is an epic, the kind of literally immersive work that connects you to the world around you even as it disconnects that world from what we like to think of as consensual reality. Jemma is a nurse in the children's hospital. She's also the target of the attentions of a loquacious angel, an angel with a mission to describe Jemma's life. And another besides: to flood the earth beneath seven miles of water. All that's left afloat is the Children's Hospital.

Or perhaps they do; we're pretty light on data when it comes to worlds ending, seeing as to how survivors are by definition few and far between. Adrian creates a gritty setting worthy of any post-blowed-up-stuff movie, but also utterly, totally different than your usual blowed-up-stuff movie. I think that fans of the Larry Niven school of post-blowed-up stuff might be quite interested. Adrian sails straight into the world of the absurd with such confidence that his patently unreal situation seems as real as the little scab on your arm, the one you got from trying to clip the hedges. And he operates on that scale of observation as well as a fascinating and frightening, terrorizing really, angelic point of view. The whole humanity-as-ants-being-studied-or-burned-by-boys-with-magnifying-glasses school of observation is rendered with the pitch-perfect language, sort of lyrical and sort of clinical. Dcotors as gods. God as a doctor. We're the disease. Everybody wins when somebody breaks the rules, even if it's not often the rule-breaker who first profits. Adrian has created the kind of compulsive vision that is purely fantastic, so pure and frightening that it might not be seen as fantastic. However, I suspect that there are readers out there who will want to immerse themselves, who are waiting to immerse themselves. Well, at 596 pages, you certainly have the immersion happening. Don’t drown. Just breathe the water. You can do it. You did so before you were born. |

|

07-25-06: Tim Powers is 'Three Days to Never' |

||||||||

"The

time is wrong."

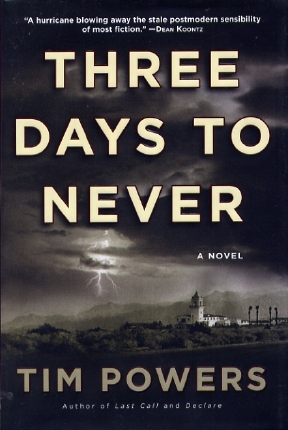

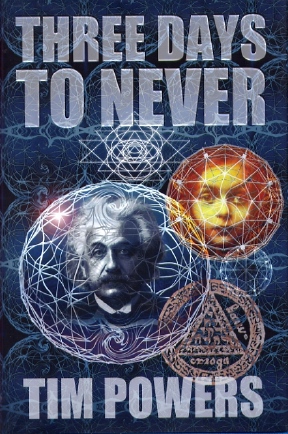

Tim Powers has been responsible for some of the best reading experiences of my life. I'll never forget re-reading 'Last Call' in the super-deluxe Charnal House limited edition on the bank of Pinecrest Lake. In the midst of beauty, I experienced a multiplication of beauty. That's the only way to explain it, and even that doesn't get close. So when I read that Powers had a new novel coming out, I was there long in advance. I pre-paid for the Subterranean Press Edition of 'Three Days to Never' (Subterranean Press ; July 6, 2006 ; $80 Sold Out) received the glorious gorgeousness of it and tried not to touch it before I put it in the Demco cover. But I waited, yes I waited, to read it until the sort-of mass market hardcover edition of 'Three Days to Never' (Wm Morrow / HarperCollins ; August 8, 2006 ; $25.95) came out, because I wanted to see if there were differences, and indeed, there were differences. Once I had both copies to hand, I could evaluate and see what was what.

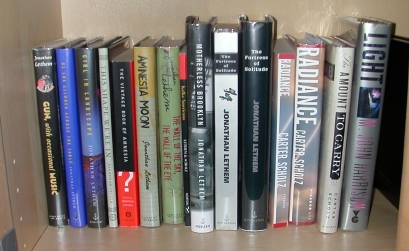

I have to say that the Wm Morrow edition is pretty darn nice. It tops off at 415 pages, but I think the text is the same, some formatting differences accounting for the page count difference. As I read this copy, I've been comparing with the Sub Press copy, and haven't found anything different. Bradford Foltz is credited with the book design and image collage, and I think they may have hit the sweet spot that will sell the book as well as it deserves. They certainly have the right vibe, and on the interior they have some stormy-cloud chapter heads that work well and look nice. If you missed the Sub Press version, then this one will do quite nicely. It's certainly easy enough to read. And that of course, is the question. Let me make this warning crystal clear: DO NOT READ THE AMAZON KIRKUS "REVIEW' WHICH GIVES AWAY HUGE SWATHES OF PLOT IN A FRIGGING HEARTBEAT. I just glanced at the damn thing, and I'm really irate about the decision to run this "give everything away plot summary" as a review. Readers know full and well that to my mind, it's quite possible to review a book without discussing the specifics that will ruin the reading experience. What Amazon / Kirkus(? -- whatever!) did is criminal. So what can we say about this book to give those who do not have a shelf that looks like this:

An idea whether or not they want to read it? Well, Powers works in two modes, generally speaking. Some of his works are purely historical; 'The Anubis Gates' and 'On Stranger Tides' are examples. These tend to be his earlier work. His latter material is more set in the current day, and this looks to be a bit more of that, though there is clearly a historical element as well. That said, the opening of the novel plunges the reader into the kind of seedy suburban landscape that we found in 'Expiration Date'. Powers really has a knack for these settings, and I love them because he haunts the same Socal settings I have haunted. The novel begins with an old woman being rushed to a hospital and a young girl finding a video tape in a run-down suburban garage. She's the daughter of Francis Merrity, lit prof out in the SoCal hinterlands, much like Powers himself. From there, things get very interesting. Powers writes beautifully detailed prose, of the sort that immerses the reader in whatever milieu he is describing. The plot here appears to involve Einstein, if the cover of the Sub Press edition is to be trusted, and I believe that's the case. Frankly, you don’t want to know any more, and I'd even suggest avoiding the DJ of the Wm Morrow Edition. (The SP edition has no verbiage on the DJ, what a splendid idea! More should do that.) Powers has a way of evoking the magical and the science fictional in ordinary settings, creating compelling mysteries that suggest yawning gulfs of surreal perception but don’t involve any of the usual supernatural clichés. Powers should be at the top of your must-buy list, your auto-buy list and your limited edition budget. This latest novel seems to have the widest possible appeal, and given the fine packaging that Wm Morrow has provided, it may do serious business. Here's the bottom line. Powers is one of those authors you carve out a special time to read, so you can really focus, sink in and enjoy his work. There are all sorts of comparisons you can make, but I'm against author-to-author comparisons; I think they tend to belittle both sides of the comparison. If you've never read Tim Powers I envy you and I suspect that this is the perfect time to start. Get yourself some quiet. Prepare to dream with your eyes wide open. |

|

07-24-06: NPR Link: "If It Comes to Pass" ; Jonathan Lethem Knows 'How We Got Insipid' |

|||||

A

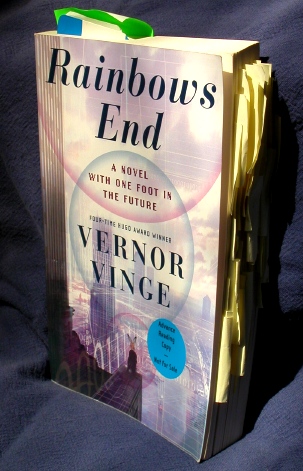

2006 Conversation With Vernor Vinge on The Technological Singularity

This project really began when I first got, then read Vernor Vinge's new novel 'Rainbows End', an outstanding novel and easily one of the best I've read this year. I pitched the idea of a report on the concept for NPR, and then gave the novel the kind of reading that involves more than a pad of stickies' worth of notes. While I generally prefer to interview writers in person, in this case, I did so via an ISDN link from KAZU in Monterey. KAZU is a wonderful station, just a hop from the Monterey Bay Aquarium. It's a lovely drive from my house to the station, tooling around the edge of the Monterey Bay. Any visit there immediately lifts my mood, because it reminds me how gorgeous this little planet is. The upshot is that my interview with Vinge went on for nearly two hours, until the news had to run. We had a great conversation, with, of course, the help of the fine folks on both sides of the connection. Vinge went to the equally well-located KPBS in San Diego, not far from where much of the action in 'Rainbow's End' unfolds. Vinge is a brilliant thinker and writer. In this segment of the interview, we talk exclusively about the Technological Singularity, from the core concept to a variety of fascinating ramifications. What I really like about Vinge and his work is that he is an expert at holding contradictory opinions; that is, his work, his fiction, his visions of the future are never monolithic or single-minded. He encompasses the complexity of human responses and relations in his work, and interweaves the good and the bad until it is rather difficult to tell them apart. In other words, he gets reality right. Readers can listen to this Eric-the-half-of-the-interview in either MP3 or RealAudio format. When I do these sorts of interviews, which I know will be for a reporting project, one of the great joys is to hear the author speak words that I know will fit perfectly into a report. What's so great about Vinge is that he provides fodder for hours of reporting. And I must say it is nice to see all this work come to some fruition–assuming we haven't been upstaged by the Apocalypse! |

|||||

|

A

Farewell to the Marketplace of Dreams I can say that I have a pretty authoritative collection of Jonathan Lethem's stuff. See?

Yes, I know; my 'Men and Cartoons' and 'The Disappointment Artist' copies are absent without leave. They’ve gone on vacation somewhere in the stacks. Hope they're having a nice time. I looked for them but after twenty minutes the reward-versus-return ratio declined into the negative and I had to get crackin' on this article. ('Men and Cartoons' showed up when I was looking for my copy of the Damon Knight Charles Fort biography.) One of the joys of writing these articles is poking through the stacks to find stuff I enjoy enough to actually write about. One of the dangers is that I can get lost, going, "Ooooh," and "Ahhh," picking up books from years past, sitting down, and getting lost in pages while lost in the stacks. Ah, the joyful hazards of this low-paying occupation. I almost tried to fetch my actually visible second copy of 'Amnesia Moon', which I bought for a song used at Logos Books, but it was behind the cut-in-half exploding lamb child's swing set. I could see it, but was hesitant to balance on the Astroturf or put my rather adult weight on the child's swing seat. So, no extraction.

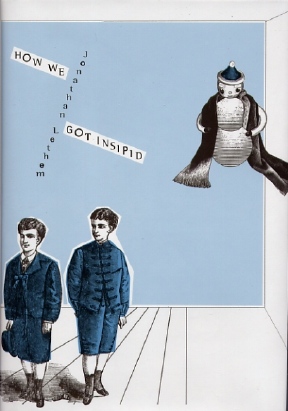

So, to the stories. Or the story of the book. Or both. What you have here is a tiny, 105-page book containing two previously uncollected stories by Jonathan Lethem. With an interesting caveat...That the publisher cannot send out ARCs to PW, BL, LJ and Kirkus, but only to the likes, of well–me. And others, I hasten to add. This is just how lucky we are... The dust jacket and interior illustrations by Blake Lethem are lovely, child-like and sinister. The book design is equally nice; largish print for my failing eyes (no reading glasses yet, thankyouverymuch, but I do have to remove my regular glasses to read, or read underneath them). Suffice it to say that when you shell out $35 for this book you're going to feel well recompensed. It's lovely and a perfect companion to your McSweeney's edition of 'This Shape We're In', in all senses. By that I mean, the book is not only like the McSweeney's deal in terms of size and format, though that is most certainly true. As Lethem tells you in the chatty, entertaining, appearing-here-for-the first-and-presumably-only-time Afterword, both of the stories found here share a sort of zeitgeist with 'This Shape We're In'. He considers them to be what I might call a tweener, something that is either a long short story or a short novella. I guess that the SFWA might want to call them novelettes, but you know, let's just call them very strange. Subterranean Press is taking a wonderful tilt towards the literary, in case you hadn't noticed. John Crowley, Jonathan Lethem–I'm really curious to see where this goes, where it ends. Readers are fortunate enough to be able to witness a literary mutation taking place before their eyes. And this new Lethem collection is a wonderful part of the process. 'How We Got In Town and Out Again' is one of a series of swipes that Lethem took at the whole virtual reality Bay-Area-Techno-Wet-Dream of the early nineties. It's almost impossible to describe, because it does not read like anything else out there. Nominated for a World Fantasy Award, it's just...strange. Lethem immerses you in a no-questions-asked situation wherein Our Hero and Heroine join some hucksters trying to get into a town so they can get summat to eat. Said hucksters are huckstering a very down-market form of VR. Virtual–and non-virtual–shenanigans ensue. This story is an utter, totally delight to read, with prose that is "as pure as the driven snow, as clear as the azure sky above" (cf A Clockwork Orange). This greatly aids one in the sort of, well, not to put too fine a point upon it, mindfucking quality of what's going on, the world that Lethem creates. It annihilates your expectations, whether they be literary (way too science-fictional, weird suits and such, what the heck?!?!?) or science fictional (way too normal, just these suits, what the heck?!?!?). I can't believe that this wasn't bounced by F&SF (where it first appeared), but then, that magazine regularly confounds expectations for the best and otherwise. 'The Insipid Profession of Jonathan Hornebom' is a Heinlein satire, that is a satire of Heinlein, not one by him. Of course, not content to lambaste the Grand Master, Lethem, tosses in healthy doses of Max Ernst, Alfred Hitchcock and Harriet the Spy. Like 'How We Got In Town and Out Again', this is another story that lives in the Twilight Zone of publishing length. But there's one other aspect of both stories that makes this volume especially interesting and to me, a must-buy. Lethem describes these stories as, "...not a farewell to the literature of the fantastic, but to the contemporary SF marketplace." This explains to me why these stories are so enjoyable. They are just themselves, whole pieces of literary invention, single-minded head-trips into a very intelligent mind. The contemporary SF marketplace is a very weird place, sort of fetishistic, caught up in a freedom that it often seems to regard with fear and loathing. This doesn't mean that there isn't a good deal of excellent literature to be found there. But it does mean that there are forms of weird literature that won't be found there. Lethem is an excellent example of this, even though he once was found there, and might easily place these stories there this day. I think he's onto something. Lethem is one-hundred percent blithe. Oblivious, even, and in the best possible manner. And he's not leaving the fantastic behind. He might have left this style behind, but you can find two fine examples in this sterling book. Worth your money and time, especially if you must have an authoritative collection of Jonathan Lethem's work. Or seek the oblivion of the oblivious. |