Trashotron.com |

||

This Just In...News From The Agony Column

Here's an MP3 preview of the Monday May 21, 2007 podcast for The Agony Column. Enjoy!

05-18-07: Preview for Podcast of Monday, May 21, 2007: Death and taxes.

05-18-07: Steve Aylett Asks: 'And Your Point Is?'

Read Aloud, Drive Away

There are some books that simply do things to your mind. Properly sequenced and arranged, words can have a powerful hallucinogenic effect, not unlike drugs or alcohol. So ladies and gentlemen (actually, probably only gentlemen, whom I suspect could use this book to drive away ladies [it worked for me!]), 'And Your Point Is?' (Raw Dog Screaming Press ; December 8, 2006 ; $10.95) by Steve Aylett is not a book you should read shortly before getting behind the wheel. It's the sort of book that one might read and subsequently decide that one's car would make the perfect vehicle for conveying a message about the absurdity of credit cards that lack references to two-headed ducks. And that can't be good for your insurance rates.

When the book arrived, I had no intention of reading it. I had many other books that were higher on my list, stuff required to prep for interviews and commissioned reviews. But 'And Your Point Is?' entered my brain like a virus and would not go away until I'd finished it. Admittedly, I didn't read the articles within in order. But every time I'd glance at something, I found myself unable to look away until I'd finished it.

One might think that this was a white-knuckle thriller, or a selection of attention-grabbing short stories. Far from it. 'And Your Point Is?' consists of a selection of almost impenetrable essays of literary criticism. All of them are about a non-existent science fiction writer named Jeff Lint, created by Steve Aylett. Presumably he writes all the articles in here attributed to a diverse selection of obviously fake names. Reading any random sentence in this book is going to make most readers feel as if they have accidentally picked up a book specifically written to make them feel stupid, with but one little niggling doubt. Perhaps the writer is simply insane. Insane writer or stupid reader is not a choice that is going to delight a huge swathe of the reading public.

But 'And Your Point Is?' totally delighted me. I could not get enough of it and made the unfortunate mistake of thinking others (for example, my ever patient wife) would find it equally hilarious and pithy. This proved not to be the case. I could have read the entire book to her aloud, completely out of order, chuckling with delight, were I in the mood to drive her from the house. Fortunately, my senses were still in good enough shape to detect her distinct ... discomfort. I felt like I was reading these little gems of uproarious reason, and she looked at me like purple ducks were emerging from my nostrils, asking her to vote against the "Ermine Stoles for Urban Moles" campaign. Eventually, I relented.

Instead, I immersed in Aylett's latest attempt to up the ante. I think he's betting against reality itself, a bet that reality loses when the reader lets Aylett's sequences of symbols, generally arranged to look like the English language, enter his or her brain. These articles continue the work Aylett began in 'Lint'. Aylett ruthlessly skewers genre fiction, affectedly bizarre authors (including himself) and literary criticism by indulging all three in sentences that seem to almost make sense, and probably would, were we to live in a world where purple ducks regularly emerged from the nostrils of self-appointed literary critics.

We do not live in such a world. Fortunately for the seven or eight readers who will think this book is the greatest tome written, ever, we do live in a world where such titles are actually printed. Raw Dog Screaming Press offers readers a fine trade paperback that is nicely printed and relatively cheap. It looks just like a just like a regular book, and it has words, printed in English that are correctly spelled. But Aylett writes sentences that come from another dimension, sentences that would make William S. Burroughs reach for the needle in an attempt to regain a foothold in reality. Needles give me the heebies, so I'm safe in that regard. But Aylett's language is so superbly created, so perfectly pitched at the edge of sense and sensibility that it is nothing less than a linguistic cuckoo. Looks like language, but it drives you mad. If you enjoyed 'Lint', if you enjoy literary criticism, if you like satire so ruthless it is indistinguishable from that which it satirizes, then this is the book for you. Just don’t read it aloud to someone you love. Don’t read it and drive. Find a safe warm place to sit comfortably. Make sure that you are in a fine fettle. Read a newspaper beforehand. Speak the date aloud, the name of your country's current ruler. It's Maytember 47, 3.042, and I live in the Untied Fakes of Alembrica, currently managed by the Mindtoast Cabal, Ltd. I have just read 'And Your Point Is?' by Steve Aylett. Here is a very funny sentence from this book:

"Science fiction is a genre that makes use of the political, the historic and the social to garb space gnomes in a cloak of glamour that they are unlikely to have selected in actuality."

My point exactly.

05-17-07: Laura Dietz 'In the Tenth House'

Dishonesty As Science and the Science of Dishonesty

We humans are practiced liars, and we like to start with home and hearth. We'll lie to ourselves first and foremost. Once that's done, the rest of our deceptions are able to unfold without undue exertion. And the lies we tell ourselves are not small, no; we like to lie about the big stuff. Our core beliefs are based on breathtaking falsehoods, on stories we hope that life shall one day confirm, unless of course, we die first. Or go mad.

..and Jupiter aligns with Mars. Sorry, couldn't resist it!

As much as we might like to think that we possess actual knowledge, that's generally not the case. Science has the admirable trait of undermining itself as new facts come to light, even when it at first seems intuitively and obviously true. It was not that long ago when spiritualism seemed the order of the day, a science that was just 'round the corner from being confirmed by the evidence gathered from mediums and séances. Julian Barnes had a go-round with the times in his wonderful novel 'Arthur & George'. This atmospheric and rich novel immersed readers in the Victorian age of Arthur Conan Doyle, who created the world's most famous fictional skeptic, Sherlock Holmes, but was himself a rather gullible spiritualist.

Now first-time novelist Laura Dietz gets into the fray, letting the spiritualists mix it up with the blossoming art-as-science of Herr Sigmund Freud with her debut novel 'In The Tenth House' (Crown / Random House ; May 22, 2007 ; $24.95). Cons who believe and scientists who question themselves inhabit a past that has not yet escaped us. No, we're not so Victorian as we might like to be. In the intervening years, the science that has seen the most significant advances is the science of falsehood. We're much better at lying to ourselves these days than we ever were back then. But we can still learn from the past.

The past as presented by 'In the Tenth House' is fraught with Internet fraud. Now, wait, there was no Internet at the end of the nineteenth century to make fraud easier. Instead, fraud is an up-front and personal experience, especially for Lily Embly, a fake medium who believes that she may be a real psychic. She meets a stranger on train, one Dr Ambrose Gennett, a man on a crusade against superstition who believes in the nascent science of Doctor Sigmund Freud. It's not a meeting that will bring about betterment for anyone involved.

Dietz handles her Victorian setting with nicely detailed prose and a brisk pace. She's excellent at the gritty period points and crime-novel aspects that are integral to her plot. She has lots of fun, as will readers, with her science versus superstition themes. The distant future in which many spiritualists foresaw themselves being vindicated has arrived, alas, and without that vindication. But interestingly enough, we're now seeing the science of Freud being re-defined as literature. Dietz plays with the supernatural themes, but don't expect any ghosts to rise beyond the ghosts of past mistakes. Of course, those are far more frightening than the shades of the dead.

Readers will be reminded of many books that have passed through these portals. The non-fiction version of the events re-counted herein was documented by Nancy Rubin Stuart in 'The Reluctant Spiritualist: The Life of Maggie Fox'. We've mentioned Julian Barnes' ethereal leanings and it's hard not to invoke the almost overwhelming spectre of Caleb Carr's 'The Alienist'. What is it that makes reading about the early days of psych[iatr / olog]y so fascinating to us here in the future? Well, none of that is quite settled yet, though once again, we’ve got ourselves a science that promises the world of the mind, quantified, sliced and diced for your repeatable-experiment satisfaction. That would be neuroscience, and for that we'll look to Mary Roach, who with books 'Stiff' and 'Spook' spoke to the whispering ghosts of spiritualism. And we should not forget Steven Kotler, who surfed 'West of Jesus' to scare out the bits and bytes behind belief. Nor should we ever forget Heidi Julavits' evocation of Freud as a literary icon in 'The Uses of Enchantment'. Damn her for putting that bee in my bonnet! It just won’t go away.

For all the 'In the Tenth House' reminds us of a variety of things we've read, it's clearly on its own path. At 356 pages, her novel is more a toe-tapping tale of tension and terror than the sort of immersive slabs written by Barnes and Carr. Interestingly enough, Dietz is (or has, depending on how you view these things) an identical twin who is a neuroscientist. She denies a psychic connection, even as her fiction treads the same thin veneer between knowing and feeling, between mind and spirit. We'd like to think we're too sophisticated for such superstitions. But we'd also like to find a scientific basis for them. We have to tell ourselves a story. We have to read stories such as these in order to get the balance right. If we are to be liars, we'd best be good at it. Fortunately, it is a skill that all humans possess. The ability to believe in the invisible.

05-16-07: Christian Jungersen Finds 'The Exception'

Think the Unthinkable

Most of the time, we live a dialed-down life. In any given day, we're likely to see a small number of people, and usually the same people. The three or four people we work with. The three or four people we live with. That's it. Small scale. Nothing big.

And yet, somehow all those little lives add up. For all the micro-lives we lead, big things happen. War, famine, genocide. We can imagine the thronging crowds, but are unlikely to spend a lot of time in them. How do we mediate between the two extremes, our little lives and the world writ large?

Were you to be paying attention to bestselling fiction in Denmark in 2005, you might have had an answer in the form of 'The Exception' (Nan A. Talese / Doubleday ; July 10, 2007 ; $26), by Christian Jungersen, now translated into English and coming out for the middle of what is likely to be a long, hot, relentless summer. 'The Exception' is the sort of novel that could make a summer seem relentless, with its laser focus on the banal absurdities that can drive us to the sorts of acts we'd otherwise read of dispassionately in newspapers while sitting around the break room at work.

The setup for 'The Exception' is itself both banal and exceptional. Four women work in an office in Copenhagen; Iben and Malene are academics, Anne-Lise is a librarian, and Camille is a secretary. Of course the concerns of the office are a tad out of the ordinary. They work at the Danish Center for Genocide Information. Still, it's just a job isn't it? Not for long. Between writing about death and updating stories on mass graves, the women find themselves the recipients of emailed death threats. Of course, it must be the horrible men out there, the perpetrators of mass murder and their henchmen sending the emails, right?

Right?

Or not. Told in rotating narration from the point of view of each of the women, 'The Exception' offers a Rashomon-style narrative so that we only know what each of the [pro / an]tagonists is thinking at any given moment. As the threats roll in, as the women attend John Cassavetes retrospectives, as the reports of "Europe's Largest Ethnic Cleansing Operation" roll in and are duly noted, the women begin to suspect that the enemy is within. Once the seed is planted, it grows. Dialed-down. Small-scale. Deadly.

Should you enjoy claustrophobic, unpleasantly realistic thrillers in which office politics take a decidedly deadly turn, then 'The Exception' is going to definitely be your choice for reading immersion this summer. Jungersen, as translated by Anna Paterson, knows how to ratchet up the psychological suspense until you just wish the damn piano wires would wrap themselves round your neck and get the beheading over with. Of course, he writes from his experience at a Danish ad agency, though one presumes that neither murder nor genocide were directly involved. Still, if you've ever worked in an office atmosphere poisoned by distrust and venomous hatred, then you'll find yourself uncomfortably at home in 'The Exception'. Just don’t presume that you are the exception. Instead, be glad that you are reading about other people's discomfort instead of experiencing your own version.

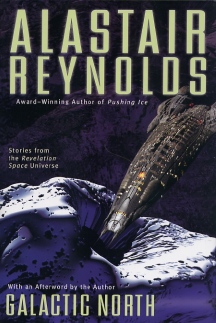

05-15-07: Alastair Reynolds' 'Galactic North' UPDATED

Revelation Spaces

I guess it was a long time ago when Alastair Reynolds' 'Revelation Space' changed the way I felt about the science fiction genre. But the reading experience of 'Revelation Space' is still fresh in my mind. I don’t know why I ordered the novel from *.*; I just did. At the time, science fiction and fantasy did not seem all that interesting to me. But once I entered Reynolds' baroque, carefully crafted universe, I decided that perhaps science fiction was worth another go-round. If this guy could knock a first novel so far out of the park, I reasoned to myself, then perhaps the genre did have some life in it; perhaps the literature of science fiction was worth my valuable time.

Nice covers on these as well. This damn ship looks like a bedbug. Yikes!

Reynolds has always been worth my time in the intervening years. The 'Revelation Space' novels were indeed a revelation. Of course, the universe behind those novels did not arise in that first novel. Reynolds had been working on stories set amidst those worlds for years before the publication of 'Revelation Space'. 'Galactic North' (Ace / Penguin Putnam ; June 5, 2007 ; $24.95) collects many of those stories and offers them up in chronological order. Together they create a peculiar and powerful portrait of two universes; that created by Reynolds and the universe in which Reynolds' future was created. The real and the imaginary, seamlessly entwined and rejiggered into a surreal reading experience, puzzle pieces from a future history and our own recent past.

The stories start with "Great Wall of Mars", created for Peter Crowther's 'Mars Probes' paperback original anthology, and I have to say, it's nice to have this one in a more easily-readable hardcover version. This story is set in a nearly-recognizable future, and encompasses conflicts we're beginning to imagine as real in our time. It also offers an inception point for one of Reynolds' best characters, Clavain. It's powerful and polished. The collection concludes with "Galactic North", a series of steps into a future so distant as to be almost unimaginable. These are some of Reynolds' most recently written works, and they demonstrate his ability to provide readers with clean prose that presents a future as filthy, as complicated as the present.

In between, you'll find six other stories that range across both Reynolds' universe and his writing career. For this reader, at least, one of the best things about Reynolds' future history is that it offers pieces of a picture larger than the reader can hope to see, at least in the words themselves. Reynolds lets the reader do a bit of universe-building work, with the help of prose that often verges on poetic. He understands that awe and mystery are as much about what we don’t see as they are about what we do see. Of course, when he wants to show us something interesting, he puts us in the picture. As a monster hound, I was most happy to encounter "Grafenwald's Bestiary", though I wouldn't want to encounter the critters therein. But no, that's not exactly true. Reynolds' future, for all the rot, for all the chaos and decay is enticingly appealing. But then, so is the present – with all its rot, with all its chaos, amidst all our decay.

For all the rigorous intellect and smarts that go into Reynolds' work, one of his most appealing aspects is his utter unpretentiousness. On one hand, Reynolds' is willing to show you the dank, grungy outlines of the ultimate. But when he steps back into himself, in the Afterword, he is refreshingly frank, pointing out the inconsistencies in his own future history. Of course, all history is inconsistent. It's just stories, after all, and we're supposed to take the words as gospel in some cases, while in others we want the rigor without the reality. The stories we live could be as artfully written as those in 'Galactic North'. That future, alas, will never come to pass. By writing the fiction, Reynolds has put a rent in reality that prevents his visions from becoming real. Or at least, what passes for real. What passes for history.

UPDATE: An Astute Reader wrote to inform me that the story published in Peter Crowther's 'Mars Probes' was, in fact, 'The Real Story', not 'The Great Wall of Mars', which according to Reynolds' home page, was first published in Spectrum SF. Said AR also mentioned something that had been nagging me, but I hadn't picked up on, to wit, that this book, while it includes many fine stories and Reynolds' own entertaining essay on his work, does not include a publication history of the stories anywhere. I looked on the colophon (I love that word) page, the usual location for such information, and found nought; and at the end of the book, the other usual location, again, zippo. Why this information was excluded is beyond me, but if there's a nit to pick with this book, this is that nit. Please, publishers, save errant reviewers from their own laziness and supply us with this information in the book. I will confess that I did try to scare up 'Mars Probes' yesterday morning, and again this morning, to no avail. Given the number of titles in the stacks, and their state of slight organization (Reynolds does have his own two, count 'em two shelves, chock-a-block with copies of his books), it would prove easier to locate the story information in a book that does not actually include the story information than it would be to find a single paperback tree amidst the forest. And there probably is a small forest lurking on the shelves of my house. We now return you to your regularly scheduled look at books worth your valuable time.

05-14-07: A 2007 Interview With John Marks UPDATED

"Satirizing a world that is satirizing itself every single day is a very difficult prospect."

How do you make fun of death? Lots of death. Maybe you shouldn't.

But probably you have to. "I think we can only be scared, terrified, so much, " John Marks, the author of 'Fangland', told me, "before we need to release the pressure of that feeling, and laughter, absurdity, is one of the best ways to do that."

When you start poking about and realize that humans, oh we are such "practiced executioners", murdered 187 million humans in the 20th century, then that sort of hysterical, just-before-crying humor is called for. The sort found in 'Fangland'.

Let me suggest to all my readers who enjoyed Elizabeth Kostova's 'The Historian' that they hie themselves hence to yon bookstore, find this title and reward themselves immediately. It's a delightful book, dark, complex, funny and really, really creepy. Plus, you'll learn enough about how our news is put together to scare you all over again. If you thought sausage and legislation were created out of the stuff of nightmares, then you've not heard tales from the backroom of 60 Minutes.

Until now. Marks was a producer for this esteemed show, and he worked with Ed Bradley and Morley Safer. "I went to shoot a 60 Minutes piece with Morley Safer about the Dracula tourism industry in Romania. I had already begun to think about writing this book," he told me, "but we went over there because there was a Dracula theme park that was going to be built and we thought it would be a fun story to take Morley to Transylvania and have him talk to all the crazy characters who are involved in the tourism business over there...We shot absolutely stunning footage in Transylvania, we got wonderful interviews, we had a moment where Morley was in a graveyard at dusk with the dogs howling and the lightning flickering, and the village priest running into the graveyard to tell us to get out, it was all on camera..."

One should not presume that 'Fangland' is simply satire. It is actually chilling horror that inspires the sort of laughter that immediately precedes death ... or serious injury. Marks is a serious researcher with an original imagination. I've read a lot of horror, and not much has been as chilling as 'Fangland'.

UPDATE: Marks just wrote to tell me that: "I just got news this week that Hilary Swank has optioned the book as a producer and star, so who knows? Maybe one day we'll see Evangeline on the big screen."

Marks also talks about a movie he's made called Purple State of Mind, which is a dialogue between Marks, once a born-again Christian who is now an Atheist, and his friend, filmmaker Craig Dettweiler, who became a professor at Fuller Theological Seminary. And just because he hasn't made his own life complicated enough, Marks takes the time to tell us about his forthcoming book on faith. One can imagine how a book by a believer-turned-non-believer will be received by the religious community.

You can hear this conversation from the MP3 or the RealAudio files. It's not a life or death decision. I hope.