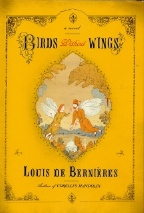

Birds Without Wings

Louis de Bernières

Knopf/Random House

US Hardback First Edition

ISBN: 0-375-41158-5

556 Pages; $25.95

Publication Date: 08-04-2004

Date Reviewed: 20th September 2004

Reviewed by: Serena Trowbridge © 2004

REFERENCES

COLUMNS

|

|

|

Birds Without WingsLouis de BernièresKnopf/Random HouseUS Hardback First EditionISBN: 0-375-41158-5556 Pages; $25.95Publication Date: 08-04-2004Date Reviewed: 20th September 2004Reviewed by: Serena Trowbridge © 2004 |

|

|

REFERENCES |

COLUMNS |

Switch off the phone, make a pot of tea and settle down for a good long read. I couldn't put this book down - and when a book is this long, that's really saying something. Louis de Bernieres' follow-up to Captain Corelli's Mandolin is not just longer, it is broader and more ambitious in scope. Like the hugely successful Captain Corelli, though, this novel sets the personal, detailed lives of everyday people against the sweep of political events, looking at how the actions of militia and politicians affects the lives of innocent civilians. The Ottoman empire is the political focus of the narrative, which is told in short chapters both in the third person, describing, for example, the rise of the politician and soldier Mustafa Kemal, whose misplaced nationalism wreaks havoc on the population, and in first person chunks, including memories of survivors. The disjointed (but nonetheless easy to follow) narrative reflects the disintegration of a community. De Bernieres' ability to incorporate a fascinating and immense history lesson with sharp close-ups of personalities and situations never ceases to amaze me.

The story is set mostly in a small village in southwestern Anatolia, where we meet a range of colorful characters who make up the life of the village. In an ethnically mixed population there is a certain amount of mistrust, especially between Christians and Muslims, but on the whole the village lives and works harmoniously side by side, having developed their own ways of dealing with things - for example, most of the women pray not only to Allah but also offer their respects to the Virgin - just to hedge their bets. Some of the tales of the characters are little vignettes which give the reader enormous insight into the lives of the people in the village, and are told with humor and pathos. There is Yusuf the Tall, who forces his son to kill his pregnant daughter, there is Lydia the Barren, praying for a child, Iskander the Potter, who makes bird-whistles and vases and whose son is one of the main protagonists. There is also the beautiful Philothei, who is Greek and betrothed to a Muslim goatherd, who is away from her fighting for most of the war, and who is destined for an early death which is tantalizingly hinted at throughout the book, and her ugly but happier friend Drosoula, who becomes the mother of Mandras who we met in Captain Corelli's Mandolin, in Cephalonia after her exile.

(My favorite humorous bit is about the camel that has become so addicted to cigarette smoke from walking behind his master that it will only move when a cigarette is inserted into his nostril!) The snapshot of life covers the position of women, religion (about which de Bernieres himself is publicly skeptical), the hardships of rural life, politics and just about anything else you can think of.

There is also a lengthy section from Gallipoli, where a character, Ibrahim, that we have seen grow up and fall in love with Philothei is fighting, in the mud and stench of the trenches. The descriptions are so vivid one can picture it in all too vivid detail; and it is interesting to see a perspective that is not a European one. De Bernieres' gradfather fought at Gallipoli and was badly wounded, and much of the novel is based on true stories from the battlefield, as well as real people, such as Mustafa Kemal and the Turkish Prime Minister, Enver Pasha. The trust and mistrust in the troops, and the occasional and unexpected camaraderie between the different sides give an insight into both the best and the worst of human nature.

The narrative is sometimes straightforward, almost unobtrusive, especially when the voice of the villagers is speaking to the reader (which leaves me with a vague impression of text that has been translated, a very clever ploy), and sometimes sweeping, colorful and complex. This is a tale of a civilization about which I knew nothing, but de Bernieres conjures it up in all its filthy, stinking, jeweled and blossoming glory. From the countryside of Eskibahce to the battlefields of Gallipoli, from churches to brothels, it is all laid out here, and it is absolutely addictive. This is no less than an epic - and with its battle scenes, its love scenes, its personal and political moments, it is indeed reminiscent of Homer or Virgil. Not only that, but it examines conflicts, both political and religious, which are ongoing to this day and makes fascinating reading in the cold light of the twenty-first century.

The title gives the book yet another interesting dimension. Near the beginning, Iskander the Potter (who has a tendency to make up his own proverbs) says:

"Man is a bird without wings, and a bird is a man without sorrows."

In the epilogues, this feeling is echoed by Mehmet the Tinsman, since he has in many ways replaced Iskander the Potter with his modern ways of working with tin:

"A long time to us is a short time to God, and a long way for us is a short way for a bird, if it has wings." Two of the main characters, whom we first meet as young boys, take the names Mehmetcik (robin) and Karatavuk (blackbird) and wear corresponding red and black shirts. As children they even try to fly, but by the end, have learned much about the worlds and its sadness, and accept that flying away is something that earth-bound creatures can never do. The metaphor is extended throughout the novel, and finally ends with Karatavuk's words "Because we cannot fly, we are condemned to do things that do not agree with us."

This is the essential human element of the book - it's all about the harm that humans inflict upon each other in a variety of ways, both deliberately and unintentionally, and so many of them wish to fly away. The bird theme is continued throughout the book, as beings who are free of the pains and restraints of mankind, while the sorrows of humanity are also all too clearly depicted. In the tragic Philothei, called by her lover Ibrahim "the little bird", reposes a metaphor for the fate of the harmonious village. Both the tragedy and the humor in the book are striking, but it is tragedy that conquers, with a cathartic sense that reminds me of King Lear, especially as Birds Without Wings closes with an epilogue explaining the survivors' lives; they might say, like Edgar at the end of King Lear:

The weight of this sad time we must obey,

Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.

The oldest hath borne most; we that are young

Shall never see so much, nor live so long.