As for the reader's experience, 'A Screenplay' is also unprecedented. 'A Screenplay' seamlessly melds the writer's life with the writer's words, as the light, which enables us to read this work casts shadows over our collective experience of reading Neil Gaiman's work. As you read 'A Screenplay', you're re-reading nearly everything you've previously read by Gaiman. 'A Screenplay' by Neil Gaiman offers a melancholy look into the mind of one of the world's most talented writers. There's the text itself, and the many subtexts that can't help but flit about the readers' minds as they enjoy this authentically mind boggling gift. Let me say that again: A gift. Yes, you needs must subscribe to Hill House's Neil Gaiman series, and no, that's not by any means cheap. If you're not up to speed on this, it's worth talking about. Expensive, yes. Still, it's a bargain by any evaluation. Just the texts printed in a trade paperback format, carefully corrected, edited and extended by the author would be worth the cost. And you get that as part of the series; the taqueria copies, I'll call them.

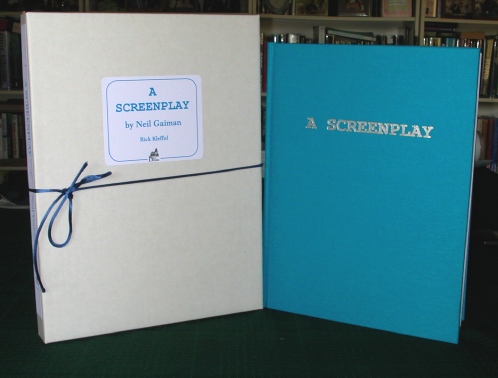

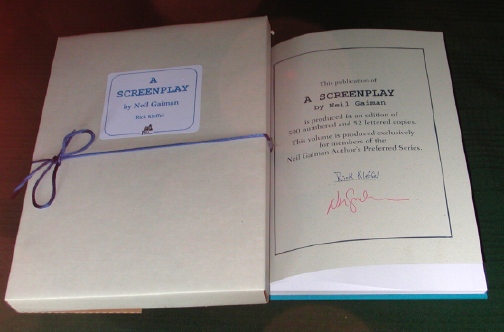

Or, as Hill House collaborator Peter Atkins put it: "I'm a book whore." And I'll admit it. I love the actual physical presence of books. Pages and paper. The smell and the weight. The tangible pleasure of holding them in your hands. Hill House provides precisely what I crave in this regard. The point here being, that just the series of corrected and extended versions of previously published works is a gift to readers, to book collectors who look upon their shelves as more than stacks of words, but rather compact art galleries. That's all we really need to keep us happy, to take our reading experience to levels of purity that few experiences of human art can match. The connection between the reader and work being read is heightened on so many levels, personalized on so many levels that the reading experience takes on hidden dimensions and reveals new mental pleasures that ordinary reading only hints at. (As long as you wear your Demco reading gloves!) Having established a baseline that's above the peaks of most publishers, with 'A Screenplay', Hill House adds a poignant and fascinating dimension to the proceedings. Gaiman's frank though brief introduction offers some insights into the screenwriting process that you might have heard elsewhere, but not quite so straightforwardly. Combined with the text of the screenplay itself, they turn 'A Screenplay' into a rewarding, unusually personal reading experience. It's your chance to chat with Neil about a time not so long ago when the first blush of fame had come his way, and he was a younger writer.

There's a melancholy at work here, that of a now-famous writer -- who has 'Mirrormask', a brand-new movie coming out next year -- reflecting back on his early career. What's interesting is what followed.

What happened next was 'A Screenplay'.

And all this

does come to pass in Gaiman's screenplay. But something else

arrives in the reading

of Hill House's

production.

Between

the content of the screenplay itself, Gaiman's short

introduction and our own knowledge of what's happened

in the intervening

years, Gaiman achieves more with the current publication

of his screenplay

than the screenplay itself.

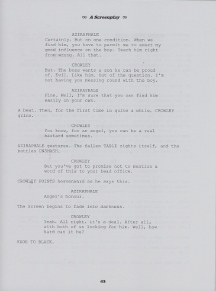

One can sense that Gaiman himself identified with his lonely Anti-Christ, trapped in a small town with a decrepit pier. Gaiman nails the atmosphere of these places in 'A Screenplay', and he successfully evokes the loneliness of his unlikely protagonist. And it's here where he manages to be authentically heartwarming, not in the Hollowood-ified scenes. Yes, there are a couple of moments in here where Gaiman bends the plot to the pressures at hand, but he does his best given the constrictions he was working under. The story is strong, shot-through with a sadness and homesick feeling even if the protagonist never leaves home. In certain scenes, 'A Screenplay's' plot does stray from the type of writing that Gaiman's readers expect. Oddly enough, one feels Gaiman's genuine affection for his anonymous creation most in these scenes. He wants it to be a successful movie-type Movie. But it's just Gaiman -- which is so much better than Movie. The third -- and major -- element of 'A Screenplay' is the dialogue. Here, Gaiman readers will find themselves on largely familiar ground. You crack a smile as you start reading that will not go away until after you close the book. They can lock Gaiman in a hotel room in North Carolina during a rainstorm but they apparently cannot lock up his subtle, enjoyable wit. The demands of the form do exert a certain gravity. Readers will find words here that do nothing more than the scene requires. But by and large, as in the screen directions, Gaiman's style seeps through the demands of the form. Reading 'A Screenplay' is a pretty peculiar experience. It's thoroughly enjoyable, but on a blurry level that's not quite fiction and not quite non-fiction. As a reader, the movie I manufactured for myself reading 'A Screenplay' was not the movie that Gaiman's written, but rather the documentary about Gaiman writing the screenplay, expressed in the form of the screenplay itself. I know that doesn’t quite parse, but then -- does reading a screenplay parse? Only if you can step back from the screenplay itself and wrap yourself in the writer's prose, in your knowledge of what the writer has written since. Years of Sandman; novels like 'Stardust', 'American Gods' and 'Coraline' all play on our inner-big screen as we read these words. 'A Screenplay' is a small piece of the past that slots into a large part of our reading present. In the proper conditions, a small figure can cast an enormous shadow. 'A Screenplay' allows readers to step behind that shadow, to know the small things that create the large darknesses. Shadows and darkness, the endless rains from Los Angeles to North Carolina, anonymous hotel rooms, Aziraphale and Crowley. They're our friends, our intimate friends now. Even more so as we get to see what casts those shadows. |