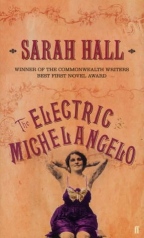

The Electric Michelangelo

Sarah Hall

Faber

UK Paperback First Edition

ISBN: 0-571-21929-2

Pages 340; Price £10.99

Publication Date: March 18, 2004

Date Reviewed: 7th October 2004

Reviewed by: Stephanie Cage © 2004

REFERENCES

COLUMNS

|

|

|

The Electric MichelangeloSarah HallFaberUK Paperback First EditionISBN: 0-571-21929-2Pages 340; Price £10.99Publication Date: March 18, 2004Date Reviewed: 7th October 2004Reviewed by: Stephanie Cage © 2004 |

|

|

REFERENCES |

COLUMNS |

Like her first novel, 'Haweswater', Sarah Hall's 'The Electric Michelangelo' gives us a detailed picture of a vanished way of life, set in the North of England. There the similarity ends. Where 'Haweswater' is dark and dour, a faded black and white portrait, 'The Electric Michelangelo' is colourful and charismatic, a vivid evocation of the seaside tattoo parlours which provided the inspiration for this novel.

Cyril Parks, known to his friends as Cy, is a fatherless boy growing up in a seaside hotel much frequented by consumptives. The opening of the story is a wide-ranging account of his childhood which comfortably takes in both the unpleasant facts of life (sickness, death, and illicit abortions) and the more positive side: Reeda Parks' touching devotion to her guests and her son.

Though Hall follows Cy closely through his childhood, she also draws us into the rich life of the town as a whole, through incidents like the burning down of the pier. When a faulty fuse sparks a blaze, the beach becomes a stage and both townsfolk and visitors turn out to see 'the show'. Moments of high drama like this one are offset by some lovely comic touches, particularly those involving a child-like delight in bodily functions and inappropriate dress. Cy loses his trousers to quicksand, gets an impromptu sex education lesson and rolls in dog dirt to impersonate a local legend, the 'boggart'.

Cy's childhood antics make for safe, comfortable reading, but Reeda's sympathy for the ailing and unfortunate means that the darker side of life is never far away. When Reeda herself falls ill, Cy's childhood is brought to an abrupt end and he is left with the choice between a safe country upbringing with her relations, or the uncertain future of live-in apprenticeship with the eccentric tattooist Eliot Riley. Riley sweeps into Cy's life with the force of destiny, and his expert, if unpredictable, tuition turns Cy into the 'Electric Michelangelo' of the title - an underground artist with home-made tattoo equipment and illicitly bought inks.

Cy gets an education in much more than art: much of the book is an exploration of what drives people to mark their bodies, and how they choose the stories their tattoos will tell. Like any great artist, Cy comes to know the extremes of human joy and suffering, love and loss. People talk to Cy as he tattoos them, and as a result the book contains a wonderful patchwork of stories in miniature which adds to the sense of a whole fascinating world of which this story is just a snippet.

'The Electric Michelangelo' is more than a picture of a past era. It is a study of the individual's past: how we are shaped by early loves and losses, and how the echoes of our childhood follow us through our lives. Time and again, Cy confronts losses recalling the death of his father in a storm at sea, before he was born. If his journey is a quest, it is perhaps a quest to understand his paternity: both his literal parentage, and the patchwork of influences that shape him as an artist.

Many of Cy's experiences, not least his involvement with the circus folk he meets on the boardwalks of Coney Island, are bizarre and harrowing, yet Hall handles them with the light, colourful touch of the tattoo artist. One of Hall's great strengths is the ability to segue effortlessly from the particular to the general, to leap from tiny, evocative details to vast overarching philosophies.

Customers' choices of tattoo, in particular, provide the opportunity for endless speculation about their real lives and secret desires. Grace, the circus rider who fascinates Cy, not least by keeping a horse in her apartment, covers her body in tattooed eyes, partly in testament to her own sharp observation about the world, and partly in rebellion against masculine attempts to dominate women through their bodies. Like Reeda Parks, Grace is a strong, independent woman who defies convention, but her more obvious defiance exacts a higher, tragic price.

Hall was a poet before she was a novelist, and this is apparent in the lyrical language and rich imagery of 'The Electric Michelangelo.' Images of the Yorkshire moors crop up throughout, culminating in a picture of Grace's stoicism as the unbending endurance of moorland rock. When the voyage to America provides him with some much-needed thinking time, so that the Atlantics becomes a tablecloth to the smashed crockery of his memories. Even Cy's unglamorous childhood has some beautiful moments, as when it begins to snow on the burning pier, and images of flame are shot through with shards of ice.

The book's many evocative images contrast with passages of blunt, naturalistic dialogue, thick with swear words and sexual innuendo, and Hall moves between the two styles with ease. After Riley's death, Cy finds a fragment of Blake's 'Tyger, Tyger', which seems to serve as an ironic epitaph, questioning the artist's ability to represent the things that really matter. Cy's pithy response is, 'And wasn't that just about right for the fucker.'

'The Electric Michelangelo' covers a vast canvas, crossing continents, spanning much of a century, and easily encompassing both the major themes of Cy's life - love, loss and pain - and the tiny, everyday details that bring any novel, especially a historical one, to life. There are passages of great poetic beauty and some deep philosophical musings, but they never overshadow what is at the heart of the book: a compelling story full of intriguing characters who remained etched on my mind long after I put the book down.