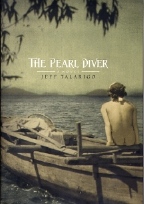

The Pearl Diver

Jeff Talarigo

Nan A. Talese / Doubleday

US hardcover First

ISBN 0-385-51051-9

Publication Date: 04-20-2004

237 Pages; $18.95

Date Reviewed: 04-27-04

Reviewed by Rick Kleffel © 2004

REFERENCES

COLUMNS

|

|

|

The Pearl DiverJeff TalarigoNan A. Talese / DoubledayUS hardcover FirstISBN 0-385-51051-9Publication Date: 04-20-2004237 Pages; $18.95Date Reviewed: 04-27-04Reviewed by Rick Kleffel © 2004 |

|

|

REFERENCES |

COLUMNS |

To lead a small life, a confined life, a life outside the thrum of everyday commerce, outside the security of small talk and big dreams, does not preclude an experience that is larger than the life itself. The limits that bind the invalid and the excluded do not themselves exclude the entirety of life. In those small moments that break through the world itself breaks through in miniature. The exiles and the excluded of this world are not exempt from life, but their perceptions and experiences are distilled through the lens of the distance the separates them. In their lives, in their miniatures, we can find our entire world encapsulated.

Disease is a natural means of winnowing the population, of reducing it by separating those who are diseased from those who are not. For much of recorded history, leprosy was the pinnacle of diseases that created a rift between those who were infected and those who were not. It did not kill quickly. Its effects were horrifically visible. Those who were infected were shunned and sent away to literally rot with their own kind. And even after a cure was available, society was slow to accept them. Leprosy is much more than a disease. It's a metaphor for separation.

'The Pearl Diver' of Jeff Talarigo's finely observed novel christens herself Miss Fuji when she's moved to Nagashima Island Leprosarium at the age of nineteen. Instead of a lifetime of pearl diving, she finds herself handed a lifetime of caregiving. Her case of leprosy is mild enough so that she can -- she is forced to, really -- provide comfort and care for those whose cases are more debilitating. Talarigo's narrative takes Miss Fuji from the atomic bomb to the 21st century in a soulful, affecting novel of acceptance and denial.

Talarigo deftly avoids the potential for a somnolent narrative by keeping his language light and limpid. The sparse, easy feel of his words carries the reader seamlessly into the small, timeless world of the Nagashima leprosarium. Though the plot is not a page-turner, the prose is. The lion's share of the narrative is told through the discovery of a series of fascinating artifacts. Each artifact suggests a story, and the stories link together to create a beautifully detailed picture of life on Nagashima. The artifact chapters slip like the pearls never taken by Miss Fuji from the sea. This is a very easy-to-read novel that slips in under the reader's radar and does not easily relinquish its grip on the sub-conscious. Talarigo's skill is to make what he's doing look remarkably easy. Most readers will finish this novel off in a day or two.

But what Talarigo is doing is nothing less than creating a portrait of the world at large, seen through the tiny lens afforded those in the leprosarium. Leprosy knows no social boundaries, and those afflicted come in occupations as diverse as gardeners and tanka poets, urn painters and musicians. There's an absolute and irrevocable fatalism in each of them. They do not, they can not contest their infection. They can not even fight it when there's a cure. Once you're known as infected, there is no cure for the knowledge of others. Injections that keep Miss Fuji's symptoms at bay do not impact the perceptions of those who know her as a leper.

In describing leprosy, Talarigo quite easily addresses the subject of AIDS and hospice care. Indeed, AIDS is the only disease to have supplanted leprosy in terms of its ability to stigmatize its victims. Every misstep, every false treatment, every casual cruelty inflicted on the patients of Nagashima has a compelling modern-day equivalent. Talarigo manages to do so with the lightest of touch, inspiring the reader to contemplate the parallels rather than dropping them with a heavy hand into the narrative. The novel inspires thought rather than requiring it. Talarigo is constantly, consistently quietly successful. On the other hand, a passage describing the horrific abortions required on the island is not in the least bit quiet. While it has as much the ring of truth as the rest of the narrative, it certainly jars the reader out of any complacency that might have developed because the author's characters seen so stable.

Talarigo uses the passage of time to great advantage in 'The Pearl Diver'. Miss Fuji's occupation before she enters the leprosarium is already timeless, unchanged over the last few hundred or even few thousand years. She lives a primitive life in a modern world where the atomic bomb has jus been dropped. Once she's in the leprosarium, time continues to filter through, rather than pass in a normal manner. Improvements in care are slow to come and slow to be adopted. The inhabitants of Nagashima see only the tip of the modern world, and yet Talarigo uses the hints of progress outside the colony to effectively suggest the whole creation of the world as we experience it. Bits of technology appear, hints of the changes the world beyond is experiencing. It's an effective way of conveying change.

The otherness of the people who live in Nagashima is total. Their money is marked. Communications with those outside are limited. While Miss Fuji uses her skills as a diver to escape temporarily from the island, once she is interred there she never leaves, even when it is possible. The condition is permanent. But there's a freedom in condemnation, an escape in imprisonment. It's the escape that any soul, whether or not it is outwardly confined can make. It's that ability to reach out to another soul, across the abyss of difference, of otherness. All that is not us is otherness. It is fearful; and we ourselves are to be feared. Only one wave, only one simple gesture is required to reach out across the ocean of otherness. This small book captures that gesture for an invisible generation.