The Iron Tree

Tor / Pan Macmillan

UK Hardback

ISBN 1-4050-4710-0

Publication Date: 19-11-2004

425; £17.99

Date Reviewed: 7-12-2004

Reviewed by: Stephanie Cage © 2004

|

|

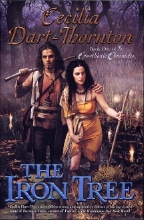

The Iron Tree

Tor

US Hardback

ISBN 1-765-31205-0

Publication Date: 02-15-2005

400 Pages; $23.99

Date Reviewed: 7-12-2004

Reviewed by: Stephanie Cage © 2004 |

|

|

REFERENCES

|

COLUMNS

|

|

Fantasy

|

|

In 'The Iron Tree' (Book One of the Crowthistle Chronicles),

Cecilia Dart-Thornton draws on an impressively wide range of

influences from fairytale and folklore, including folk tales from

Yorkshire, Lancashire, Ireland and the Fens, as well as a smattering

of Norse legend. (A word of warning here: the references at the back

of the book, while fascinating, contain something of a plot spoiler,

so stay away from them until after finishing the story.) One of the

book's most extraordinary features is its vivid depiction of a whole

host of supernatural apparitions, from spectral riders in the desert

to weeping maidens in the marshes.

Dart-Thornton convincingly evokes a society used to coexisting

with magical creatures, spells and sorcery. When we first meet

Jarred, the book's attractive and intrepid hero, he is agonising over

the use of a protective amulet, which is one of his few ties to his

dead father. He's been told it bestows invulnerability on the wearer

- a useful trait when the land you are travelling is beset with

half-human bandits known as 'Marauders' as well as various 'eldritch

wights', both 'seelie' (benign or even helpful) and 'unseelie'

(malicious). Jarred would prefer a fair fight without supernatural

protection, but ultimately his promise to his dead father carries

more weight than the pricking of his conscience, and the amulet stays

on.

Determined to prove himself the equal of his unprotected friends,

he takes on all the dangerous tasks. Initially, in the safety of his

village home, these are fairly insignificant, such as retrieving a

telescope from the desert before its absence is missed. However, when

he sets off with a group of village lads on a quest to see the world

and learn more of his dead father, they encounter ever more dramatic

dangers.

They also encounter Lilith, an innocent beauty with a sword of

Damocles hanging over her in the form of the madness which afflicted

her grandfather and her mother, and which her family are beginning to

suspect may be inherited. The portrayal of the mad grandfather is

delightful, and seems to owe a great deal to Hamlet in his mad phase.

The grandfather doesn't quite mention hawks and handsaws, but 'they

say the conger is a candle-maker's daughter' is surely the Marsh

equivalent of 'they say the owl is the baker's daughter.' Lilith and

her mother recall Ophelia in their bewildered helplessness in the

face of madness, as well as their love of wild flowers, which brings

to mind Millais' Ophelia.

Not surprisingly, Jarred falls instantly in love with the

beautiful Lilith and eventually finds himself adopting a new quest:

to find out the origins and cure of her family's affliction. In the

course of his two quests, Jarred learns something of the truth about

his family origins, but the information soon puts both him and his

beloved in further jeopardy, leading to an extraordinary but

believable series of adventures.

The city lowlifes to whom he turns for assistance are also

well-drawn, with a very Shakespearean blend of caricature and pathos.

Fionnuala, in particular, both touches and repels the reader with her

mixture of genuine devotion and sheer selfishness.

The romance of Jarred and Lilith is a complicated story, summed up

by the narrator in the Prologue as:

'A chronicle of jealousy and revenge, of wickedness and justice,

and of love. It is an extraordinary tale, extraordinary and tragic;

yet there is no tragedy from which some goodness doth not arise, as

the green shoot doth sprout from the cold ashes of the wildfire.'

Thankfully, the verbose narrator then disappears until the

Epilogue, where he makes a brief appearance, which demonstrates that

tragedians weeping at their own stories are every bit as annoying as

comedians laughing at their own jokes.

Prologue and Epilogue aside, Dart-Thornton achieves a largely

convincing pseudo-medieval style. Poetic descriptions (somewhat

reminiscent of Keats, whose poem 'St Agnes' Eve' was an inspiration

for some aspects of the book) coexist comfortably with everyday

actions in passages such as this:

"In the western skies the sun was liquefying in rivers of

iridescent pink and gold, the usual splendour of a desert sunset, by

the time the boys finished devising and practising their tactics for

winning the football game."

However, the peppering of archaisms like 'naught' and 'gramercie'

occasionally becomes irritating, as do linguistic tics like the

characters' continual use of the phrase 'The knowledge is not at me,'

which by the end of the book left me yearning for a simple 'I don't

know'.

If 'The Iron Tree' has a fault, it is the impression it sometimes

gives that the author is trying too hard. All the ingredients of

great epic fantasy are here: evil sorcerers, curses, ghosts, amulets,

magic jewels, a powerful hero and a helpless heroine, described in

flowing poetic language. This has the unfortunate result that at

times the book seems to have been written by following a recipe for a

fantasy bestseller. First catch your wizard...