When you read a book, particularly a novel, it's easy to get immersed

in the narrative and forget that the writer is out there with a tool

kit, picking up prose pliers and spanners to assemble those words,

one by one, into the sleek vehicle that carries you away into the

reading experience. All the protocols that help a writer assemble

mere words into something far greater than mere words are so familiar

to most readers that they’ve become invisible. Similes, metaphors,

dialogue, plot points, characterization, narrative perspectives,

that whole mess of things with which writers craft the whole of a

story, a book, a novel – they vanish the second we actually

start reading the first paragraph.

But what if there are no paragraphs? What happens when the primary tool

a writer uses is so unfamiliar to readers that a glance at the page makes

it glaringly obvious that the reader is being written to? The game is

changed. All the norms we accept without question are now exposed for

what they are; prose devices meant to trick the reader into reading and

sublimating his thoughts into the reading experience crafted by the writer.

If we're faced with something unfamiliar, we're forced to accept the

notion that we're engaging in a contract with the writer; they write,

we read.

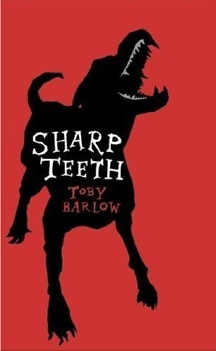

'Sharp Teeth' by Toby Barlow is written in free verse. With the first

line on the first page, readers are made aware that they're engaged in

an unnatural act, that of reading.

"Let's sing about the man there

at the breakfast table"

That first line break is indeed a make-or-break deal for many readers,

but it shouldn’t be. Barlow crafts his reading experience with

an under-used building block, but 'Sharp Teeth' delivers in spades and

frankly, makes you wish more writers would bring the sort of control

that he brings to this exciting and delightful first novel. At first

all that white space on the page seems alien. But beyond the line breaks,

'Sharp Teeth' is otherwise a normal novel, albeit one that's filled with

blood, mystery and some very engaging love stories that even a guy can

truly appreciate.

The plotting for 'Sharp Teeth' is complicated but not overly unusual – beyond

the fact that many of the characters are werewolves. Anthony, the man

at the breakfast table, is looking for a job and manages to pick up one

as a dogcatcher. That night, he meets a woman at a bar who buys him a

drink, and she seems both interesting and interested. Lark is the male

leader of a pack of werewolves. The woman with whom Anthony had a drink

used to be the lone female in his pack of werewolves. Her departure puts

one of his master plans on hold while he finds out where she went. Others

move forward, and faster as he find there are other packs in LA. People

die, and a lone cop starts to sense that something's amiss with the dogcatchers

and the dogs. He gets phone calls directing his attention to Lark, Anthony,

the woman. Paths cross, double-cross and converge. Dogs play bridge and

people die.

This is a novel about werewolves, but it doesn't limit itself with lots

of genre trappings. The supernatural is handled with total restraint

and vivid clarity. Barlow's werewolves are not enslaved to the moon to

drive their transformation; they can change at will. They don’t

change into wolves, per se, but something like large and fairly fierce,

if need be, dogs. We find out enough history to understand the backdrop

but not so much as to confuse matters. Barlow's hidden world of werewolves

lies comfortably under the real world. Barlow uses the supernatural tropes

with the same ease and intent that he uses the free verse format; to

tell an exciting story in an exciting manner.

Because the plot for 'Sharp Teeth' is complex even for a supernatural

mystery, readers need great characters to rein in their attention. Barlow

succeeds at creating and managing a large cast of characters, some of

whom are merely human. Anthony is an engaging everyman, like most of

the characters, barely making ends meet at the bottom of the social ladder.

His new girlfriend is trying to escape from her old life, but some habits

die hard, especially those that involve hunting and killing and the utter

freedom of being a werewolf in the canine form. Lark looks as if he'll

be more of a background character than he turns out to be as the plot

unfolds, and we as readers enjoy his low-key ambition. Lark sends two

members of

his pack, Cutter and Blue, into the world of tournament bridge, and their

adventures are just delightful. Peabody is the lone cop who twigs to

a connection between the dog packs and some meth labs. Threading all

these

characters

together are superbly crafted emotional ties that keep the reader riveted

no matter where or with whom you are in the story.

For all the complexity, for all the well wrought emotion that Barlow

brings to 'Sharp Teeth', the free verse proves to be the perfect format.

On one hand, the "cantos," I guess you'd call them are like

super-short chapters. This makes the book alarmingly easy to read, and

it reads like lightning. It doesn't seem like you're reading free verse.

But Barlow does use his line breaks and his pacing and even, once in

a very great while, meter and rhyme, to excellent effect. 'Sharp Teeth'

is written in free verse for a reason – Barlow is able to tell

a complicated story in an abridged format. Had this been a "normal" novel,

it might have been much longer and more difficult to suss. As it stands,

it's tighter than a noose at noon, with plot and character rewards that

will remain in your memory long after you've finished the book. And that's

the big deal; when you finish 'Sharp Teeth', you'll realize that you've

just read a great novel in free verse. Sure, it needed to be written

this way; all those threads needed more careful weaving than the normal

superstructure of a novel could support. But in the final analysis, 'Sharp

Teeth' is an excellent, if unusual, love story and mystery.