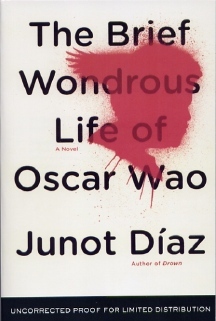

You've heard the phrase "larger than life." No one would use

that term to describe Oscar Wao, or even the justly lauded novel bearing

his name. Here is a man -- an overgrown boy more precisely -- whose

very absence of ambition, bravado, adventure, and (yes) life defines

him, like the negative space in the center of a doughnut. He is fat.

He is nerdly. He is demure. He is a dreamer. He is who nobody wants

to be, but who everyone fears they could become. He is also, at the

end of his brief, wondrous life as vividly told by his best friend Yunior,

a brave, gentle soul, whose actions reveal the humanity in the quietly

steadfast. And that is almost enough to turn this book, a virtuoso first

novel from Junot Diaz, into an instant classic. If (like its eponymous

hero) it falls short of greatness, it nevertheless reminds us how small

the rest of the world is.

The book begins, like Kill Bill (another genre smashup), auspiciously

enough with a laughably serious sci-fi quote: "Of what import are

brief, nameless lives . . . to Galactus??" Diaz follows with a

high-brow excerpt from poet Derek Walcott: "Christ have mercy on

all sleeping things! From that dog rotting down Wrightson Road to when

I was a dog on these streets . . . I have Dutch, nigger, and English

in me, and either I'm nobody, or I'm a nation." And that, more

or less, previews the novel's tone: a teetering balance of high and

low, comic book and Shakespeare, nerd-dom and Third-World politics.

The theme of alienated adolescents fantasizing about mutant powers shares

the same pages as that of immiserated, impotent minorities trapped in

sub-tropical tyrannies. Diaz focuses on the Dominican Republic, the

home of the Leons, expatriates whose ancestors were decimated by the

brutal dictator Rafael Trujillo and who now live in (where else?) New

Jersey, where the last male scion spends his days watching anime, reading

fantasy, orchestrating role playing games, and writing an endless sci-fi

epic.

Oscar, appellated Wao after his abiding love for Doctor Who,

takes after another comic novel hero, Ignatius J. Reilly of 'A Confederacy

of Dunces'. He is a man of girth and stunted sexuality sublimated into

baroquely stilted verbiage, uttering salutations such as "Hail

and well met," intoning gravely after a jog "I shall run no

more," and wondering whether orcs "at a racial level"

imagine themselves to look like elves. The narrative, voiced by a room

mate from college, places him at the center of the story, but the novel

circles through time, sketching a family history reaching into the post-war

past of the Dominican Republic and the origins of the Leons' terrible

fall. Thus, the viewpoint switches to Oscar's sister, then his mother,

grandfather, then back again to "the Dominican Tolkien."

The family member's destinies purportedly trace a "fuku" or

curse, stretching across time and space. The reader can observe Diaz

striving for a flavor of magical realism: Isabel Allende meets Gabriel

Garcia Marquez. But, it is one ingredient too many in this heady Caribbean

brew. He supplies a couple coincidences and visions that lend themselves

to an otherworldly interpretation, but the story's heart simply isn't

in it. This is a character study; almost a short story collection of

interrelated life vignettes. In its attention to detail and the sympathy

afforded each character, the novel merits comparison with the intimate

short work of Alice Munro. At the same time, Diaz can muster a prose

so bleak as to be drawn from a Cormac McCarthy novel:

At one point they passed through one of those godforsaken blisters of

a community that frequently afflict the arteries between the major cities,

sad assemblages of shacks that seem to have been deposited in situ by

a hurricane or other such calamity. The only visible commerce was a

single goat carcass hanging unfetchingly from a rope, peeled down to

its corded orange musculature, except for the skin of its face, which

was still attached, like a funeral mask. He'd been skinned very recently,

the flesh was still shivering under the shag of flies.

Unfortunately, the stories are so individually strong that they exert

a centrifugal force on the central narrative, resulting in a less-than-dynamic

pace and plot.

While the realism and lack of sustained ambiguity keep the atmosphere

natural,

the real wonder here is the narrator, a consummate verbal showman who

recombines Dominican Spanish and American English into a stream of vibrant

sound and sense, rhythm and rhyme. Like Arundhati Roy or early Salman

Rushdie, Diaz explores the fringes of natural sound and language, delighting

in a childlike play with the skin of thought. The conversational discourse

employs copious use of footnotes, strewn at times in short bursts of

thought confetti and at others in long, winding discourses on minor

character backgrounds and Dominican history. Diaz demonstrates a technical

mastery here that was rightly commended; his youthful, player-narrator

could, without just the right balance, very easily have sounded like

a puff-chested caricature of Caribbean machismo. In its studied effortlessness,

the novel recalls A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, the work

of an author who also received a Toronto blessing of adulation with his

debut, only later to be reprimanded for indulging in style at the expense

of substance, and then even later redeemed by a "straight"

story about an African child refugee.

This is a book that tugs at you, wears down your defenses. At once supremely

silly and profoundly serious, it is a book running on fumes and adolescent

adrenaline that keeps going because it never condescends to the reader

and consistently sustains an aura of authenticity. In its preoccupation

with the effluvia of marvelous pop fiction, it is also a love letter

to the past 30 years of American culture before the Internet revolution

and the i-pod generation, when our entertainments were a little less

hi-tech and yet (by virtue of raw imagination) more fully realized than

ever since.