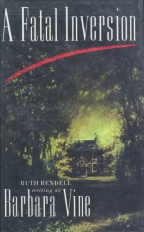

A Fatal Inversion

Barbara Vine (Ruth Rendell)

Viking / Penguin Putnam

UK Hardcover First

ISBN 0-670-80977-2

Publication Date: 1987

317 Pages; £10.95

Date Reviewed: 07-15-02

Reviewed by Rick Kleffel © 2002

REFERENCES

COLUMNS

|

|

|

A Fatal InversionBarbara Vine (Ruth Rendell)Viking / Penguin PutnamUK Hardcover FirstISBN 0-670-80977-2Publication Date: 1987317 Pages; £10.95Date Reviewed: 07-15-02Reviewed by Rick Kleffel © 2002 |

|

|

REFERENCES |

COLUMNS |

After Ruth Rendell turned the mystery world upside-down when she penned 'A Dark Adapted Eye' under the pseudonym Barbara Vine, nothing was ever the same. Rendell turned to the Vine pseudonym to write novels outside the style of her usual 'novels of suspense' or the Inspector Wexford mysteries. Those novels show a pretty wide range of style. The Vine novels actually manage to expand that range considerably, and they expand the range of the mystery genre as well. Last year, the inverted structure of Christopher Nolan's clever 'Memento' knocked audiences off their feet with it's disorienting time reversals. But one need only look back to Rendell's Vine novels to see that the technique was not all that new. But 'A Fatal Inversion' has much more going for it than an interesting technique of narrative construction. This novel will crystallize for any reader a particular place and time so clearly, so cleanly, so perfectly that it will replace their present reality, it supersedes the reader's current experience. As the readers return to the summer of 1976, to a country house in Suffolk in the suffocating heat, the layers of memory are shuffled as easily as a well-worn pack of cards.

The novel begins as the remains of a child are excavated from a pet cemetery on the grounds of the Wyvis Hall. They date from the summer of 1976, the summer that Adam Verne-Smith and his friends lived there, in an upscale version of the free-love communes that grew like weeds in the summer fields. Vine masterfully evokes the days of anyone's lost post-college youth, the heat of the summers, the ultimately evasive climactic, meaningful moment that remains hidden dense shade and blinding sunlight. She slides her characters in and out of relationships in the present day and in the re-constructed past. The writing is so powerful and so strong, most readers won't immediately realize that they are reading a mystery.

However, as with all mysteries, 'A Fatal Inversion' heads towards a revelation. What Rendell as Vine does so well is misdirect the reader, to suck the reader into the characters' heads and the characters' lives without the reader realizing that this is being done. Don't expect a fast-paced tension-laced thriller. 'A Fatal Inversion' sneaks up the reader, and even if you know that something is coming, most readers won't know where it is coming from. Somewhere out beyond Wyvis hall there is a real world that is waiting for all the characters in 'A Fatal Inversion'. It's waiting for the reader as well. But it will have to wait, for Rendell has just one more thing that she'd like you to see. When she's wearing the Vine face, Ruth Rendell is no more writing mystery than was Emily Bronte when she penned 'Wuthering Heights'.