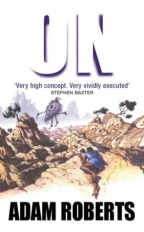

Science fiction and fantasy are often about taking the world we

know and "turning it on its side". Lots of writers do this in all

sorts of ways; magic works and science doesn't, for example, or

vampires are real. But nobody has ever quite done what Adam Roberts

does in 'On' -- turn the world literally on its side. He does so by

carefully creating a gritty, detailed point of view, setting up rules

and sticking to them, and intriguing the reader with an almost

archetypal SF mystery. How did the world get this way? Why does it

work like this? And, like any mystery writer, Roberts plays fair,

giving the reader clues as to the nature of the mystery. Most

importantly, he creates his mysterious world and then lets us in on

the magnificent secret through the eyes of his to start with

naïve character. It's an incredible point of view. You get to

see the world from above the wall.

Tighe is a prince in his village on the worldwall, but it doesn't

mean much. Life is hard, a scrabble for every goat, every bit of

bread, every insect he and his family are able to catch and eat. The

wall rises above them farther than they can see and falls below them

farther than they can see. 'On Tighe's eighth birthday one of the

family goats fell off the world. This was a serious matter.' Though a

prince, Tighe's father performs menial work for other villagers. His

mother is unstable, prone to furious rages and beating her son with

whatever might come to hand. With luck, Tighe might one day inherit

the family goats, his father's life. Tighe is not lucky; he's

special. He falls off the world -- and survives.

What he finds is another part of the Wall, with larger ledges,

bigger crevices, more people than he could ever have imagined, doing

something he could never have imagined -- following the War Pope to

war. But life is no easier in this realm than it was in his village.

The imagination behind human cruelty knows no bounds, and Tighe has

no expectations that it could be anything more or less than he is

shown. Roberts uses his youthful, naïve character to introduce

us to a world that is at once familiar and literally on its side. His

careful, clean prose creates for us an existence that seems as

casually violent as the real world, as primitive as parts of our

world are today.

But there are clues there, bits of plastic and technology that

suggest this world was once different. (There is also an appendix

that should definitely be left until AFTER the reader has finished

the book.) Once Roberts has thoroughly grounded us in his unique

vision, he begins the second twist, to turn the readers' new world,

Tighe's daily struggle, into something more, a grand thought

experiment. There's a reason the World is a wall. Yes, life is

precarious, but there's more, much more. Roberts can tell us

everything, and he does. It's a joyous, terrifying revelation.