The life of any piece of prose in the reader's imagination is

intensely variable. The experiences created by reading something,

anything, lasts as long as the act of reading. Beyond that, the

reader may carry the memory of reading, or the false memories created

by reading for minutes or decades. The decision as to how long that

memory lasts is up to neither the reader nor the writer. It just

happens. Short fiction is just as likely to last a lifetime as the

latest doorstop. It's not how long the fire burns but how brightly.

Afterimages, burnt into your mind, tiny etchings, phrases and

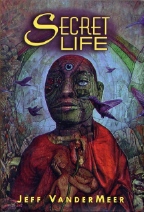

imagery curled on the floor. This is the heritage of 'Secret Life',

the Golden Gryphon collection of short fiction from Jeff VanderMeer.

VanderMeer burns brightly, even when his subject matter is dark as

night. This collection offers an astonishing variety of subject

matter and styles of execution. But most importantly, it offers

intensity. These are glimpses of the sun that flicker long after the

vision afforded by reading them.

Readers familiar with VanderMeer's oeuvre will enjoy his visits to

familiar fictional locales. He returns to Ambergris, the setting for

'City of Saints and Madmen' in five of the stories collected here.

Reader's can't help but be struck by how confidently, how seamlessly

he segues from a world that seems familiar into a world of fantasy.

In 'Learning to Leave the Flesh' he accomplishes this with a

matter-of-fact narrative voice that leaves the reader no room to

question as events and description become increasingly peculiar. In

contrast, 'Corpse Mouth and Spore Nose' operates on a far more

surreal level. But in 'Exhibit H', he writes fictional non-fiction,

offering an excerpt from a Tour Guide. The result is quite comedic

with nicely turned horrific undertones.

In 'Detectives and Cadavers' and 'Balzac's War', VanderMeer

extends the terrain of the science fictional setting for 'Veniss

Underground'. He delves in the past and future of his Dystopian

vision in which bioengineering has poured into the streets like so

much sewage. The results are particularly disturbing, a combination

of surreal imagery and all-too-real emotions wedded in a blood bath

from which few will emerge unscathed. 'Balzac's War' is a complex but

compact novella of a war between humanity and its literally faceless,

soul-less creations. On the other hand, 'The Sea, Mendeho and

Moonlight' is a poignant tale of loss and love, a myth from the

future VanderMeer has created.

The majority of the stories here are not connected to VanderMeer's

signature works. In them the reader will find a variety that is

shocking and bracing. The title story, written in shimmering

glimpses, tells the story of a building that has a life of its own.

VanderMeer slides easily from a surreal vision of corporate life that

has become so ingrown it's mutated into the disquieting thoughts of

those who work there. The world we think we know becomes an example

of why we can never know, never trust this world or any other. In

'Flight is for Those Who Have Not Crossed Over', VanderMeer turns the

Latin American school of magic realism into a venue for the horror of

self-loathing. 'The Festival of the Freshwater Squid', which edges

into Ambergris territory, is nonetheless set in a very real Florida.

This is a perfect example of Vandermeer's best work. It's full of a

rigorous whimsy as it gorgeously renders in prose the entirely

fictional habits of an entirely fictional species and culminating in

an image of loveliness and power.

As a child, VanderMeer apparently traveled extensively with his

parents, who were in the Peace Corps. Here, his experiences are

rendered into fiction both beautiful and terrifying. A cycle of

stories set in Peru, both in the past and present offer some of the

highlights of this collection. From 13th century Cambodia to London

during the blitz to Tennessee in the early 20th century, VanderMeer

demonstrates he just as confident in the real world as he in worlds

of his own creation.

The prose here is always fine, and the style is suitably

chameleonic. VanderMeer goes so far as to write stories in the second

person and he makes them sing as effortlessly as prose poems like

'The Machine', a dream-like work that exudes the sort of wrongness

that Lovecraft sought in "non-Euclidean geometries." But in reading

the collection, one story after another, as if it were a novel in

parts, or slowly, one story at a time, over a period of weeks or

months, readers will note that VanderMeer is consistently achieving a

startling feat. He's writing stories about subjects both science

fiction and horrific that never, ever read as if they were genre

fiction.

This is the truest strength of the stories in 'Secret Life', the

secret life that animates all the writing to be found between these

covers. VanderMeer's prose -- no matter what style he's working in,

and there are many to be found in these stories -- is intensely

literary. But then, these stories don't feel as if they are literary

fiction in the midst of the reading experience. VanderMeer's fiction

leads a mayfly life. His language burns brightly, sliding from one

word to the next, slickly avoiding expectations, the reader's

inherent inclination to categorize a work as belonging to one group

or another. The stories force themselves into our conscious and

exclude every other word, every other experience. There they are:

each story bursts into life then flickers back into nothingness,

leaving only itself. Leaving only the reader, the book in hand. You

can close the book. But the stories remain alive, the words follow

one another and lead back to one another. For a few moments you are

there. You are there forever.