|

|

|

This Just In...News from the Agony Column

|

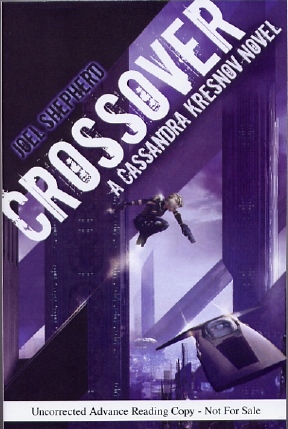

06-30-06: Joel Shepherd is Looking to 'Crossover' |

|||

Raiding

the Australian Paperback Racks

But the reasons we read are within the books themselves. So before we go trend spotting, let's look at just why you should buy and probably enjoy 'Crossover'. The setup is not unfamiliar, but it's certainly interesting. Humanity has spread itself across at least part of the galaxy, planet-hopping from star to star. And humans being the feisty bunch they are, have separated themselves into two factions, the liberal League and the conservative Federation. (Warning: "liberal" and "conservative" may have shifted in meaning in Shepherd's novels. Pontificate politically at your own peril!) Cassandra Kresnov is an "artificial person", a pneumatic android, intelligent, dangerous and really hot. Disenchanted with the League, she heads deep into Federation territory, and ends up in a hotel room on Callay, in the capital city of Tanusha. Flying cars. Movie stars. Swimming pools. Y'all come back now, y'hear? Oh sure. It all seems pretty luxurious, but when you're a powerful, intelligent and (hot) creative android, whatever past you might try to leave behind is coming to catch up with you. With a net result that those who can die do, and those who cannot die teach others how to do so. Cassandra falls into the latter half of the equation. All the politics and culture wars she sort-of hoped to leave behind are going to rear their ugly heads. Other heads will roll, but for readers the treat is Shepherd's immersive writing style. That and his ability to integrate rip-roaring noir plots with perceptive character development that spins off some interesting thought-experiments about how technology will make our lives bigger but not necessarily better. Shepherd also has a rather droll sense of humor. He pumps up his borderline clichés to make them snicker at themselves. The reader gets to join in. But the good news just doesn't stop. 'Crossover ' is just first of the Cassandra Kresnov novels. Anders is a perceptive editor, and he found this novel sitting on the shelves Down Under. Not only 'Crossover', however. There's a trilogy of Cassandra Kresnov novels. The follow-ups are 'Breakaway' and 'Killswitch'. Neither is available stateside yet, but just give Anders time. (And sales.) They are available now, presumably from some Aussie dealers, but they're not hardcover originals, so it's probably worth the wait for the Pyr trade paperbacks. The Cassandra Kresnov trilogy makes a trilogy of trilogies about cyberpunkette heroines with noirish adventures in Blade-Runner-esque futures. Elizabeth Bear was the first to come to my notice, with 'Hammered', 'Scardown' and 'Worldwire'. Earlier this week, I wrote about Marianne de Pierres' Parrish Plessis trilogy–'Nylon Angel', 'Code Noir' and 'Crash Deluxe'. If only de Pierres had crammed her title words together, then we could really go for a run. But then we'd have to ask Bear to retrofit the title of 'Hammered' to say, 'Jackhammered'. Works for me! Still, this is a trend that is not going to go away. Not if the success of Sue Grafton is any indication. Serial mysteries sell quite well, and the SF-element (and the black leather) pump up the appeal for the male audience, where, surprisingly, it needs pumping. Women are buying more books these days, and I can see the appeal of these cyberpunkettes to just about anyone who wants a novel that is fun to read, er stimulating, and thought provoking. Perhaps not Big Thinks, but Thinks. One cannot and should not run a mental marathon every damn day. If these writers decide to follow up these trilogies, which are at present, thankfully self contained, then readers and publishers could be in for a real treat. Remember that Grafton, for most of us, started out as a kind of cheesy series of gimmicky paperback novels. (Though they were first issued as hardcovers, many never saw them until the paperback strated creeeping across the racks.) To my mind, these writers and their work have much of Grafton's appeal with (for me) the added interest of the science fiction background. That may at present turn some of the less adventurous readers away, but in the long run, I think it could bring them more. A layer of SF on top of a solid foundation of mystery makes for an engaging read. And finally, there's the HarperCollins connection. Published by HarperCollins Voyager imprint in Australia, one might presume that the extensive and well-run HarperCollins US branch would be the first to run with these novels. But they didn't. This often happens in the publishing world, and while I understand some of the reasons -- different operations, different crews, and different countries -- it still seems ludicrous that HarperCollins US didn't snag these back when they first came out. But to tell the truth, I'm happy to see Lou Anders and Pyr get them, because Pyr will treat them right, and they managed to get them in front of my nearsighted eyeballs. All I had to do was to Just Look Around. |

|

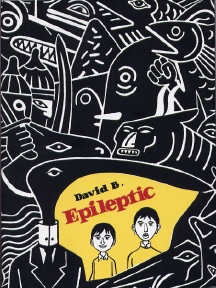

06-29-06: David B.'s Big Brother is 'Epileptic' |

|||||||||

Graphic

Novel Memoirs

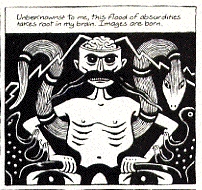

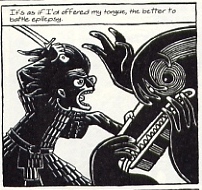

And, of course, David B., born Pierre-François Beuchard, whose mammoth 'Epileptic' (Pantheon / Random House ; July 4, 2006 ; $17.95) is now out in trade paperback. First released as a US hardcover early in 2005, this collection of all six volumes between two soft covers is nothing less than epic and astonishing. And a quick glance demonstrates something about the graphic novel medium that indicates why it will continue to overtake the written memoir. While the written memoir must cleave to the truth to retain authenticity, the graphic novel memoir can speak the truth while illustrating the feelings of the author. The "it's not how it was, it is how it felt" argument that comes when someone writes about the exaggerated feelings they aim back at their youth becomes a moot point. In a graphic novel you can both speak the outer truth while illustrating the inner truth.

'Epileptic' charts the childhood of David B., his big brother Jean-Christophe and their little sister, as they try to cope with Jean-Christophe's illness. It is a memoir that must, in order to adhere to the truth, venture into realms of the imagination. David B. (Pierre-François) thought that he might catch the disease from his brother, and in order to gird himself, he spoke to imaginary beings, girthed himself with "armor" and began at an early age to create a fantastic world in comic books.

Pantheon has done a wonderful job on this trade paperback version, though I have to say that it is rather small. What's there is pristine in every way. And yes, I can understand the inclination to try to turn this into a Quality Paperback bestseller. I think it will achieve that status, at least here in northern California. I don’t care if graphic novel memoirs are a fad. I care if they're good. 'Epileptic' is better than good, it’s great. I don’t know how I missed this back when it came out in hardcover, well I do. I missed it because I wasn't paying attention. Rest assured, I'm paying attention now. |

|

06-28-06: Scott E. Smith Excavates 'The Ruins' |

|||||||||

Digging

the Appeal of South American Horror

When I think of South American horror, and when I first saw 'The Ruins', three other titles immediately leaped into my mind. The first was 'The Dragon' by William Schoell, one of my all-time favorite monster novels. Published at the height of the horror boom, in 1989, 'The Dragon' was brought to you by Leisure Press, complete with a badly-touched-up iguana photo for the cover of a meant-to-dispense paperback. The premise was pretty simple. An archaeological expedition, searching for the lost city of "El Lobo" finds that city beneath a Mexican mesa. What they find however, is no set of mummified skeletons in a desert pueblo. It's an enormous, living bio-weapon, part myth and part Alien-rip-off. And, to this reader, all entertainment. Schoell told me in an interview for Cemetery Dance that, "Despite-- or because of -- its many "cheesy" elements I think 'The Dragon' worked well on a creepy, entertaining level." I'd have to agree. You get a plague of "pregnant" men, giving birth to giant slugs. You get a living computer. You get walls that shift and drip slime and spread disease. And yes, eventually, you do get a dragon, one that comes off quite well. Schoell makes the most of his location, evoking the ancient cultures and that sense of "deep time" to create a great overblown sense of the fantastic, an "anything goes" potential after which, well, everything goes. Schoell wasn't writing horror for the literary hardcover horror audience; in fact, he included an afterword wherein he let it be known that, "..the tale you have just read is -- for shame! -- one chiefly of entertainment." In that he succeeded, offering readers the literary equivalent of a Roger Corman movie with a $200 million dollar budget. It was a memorable novel for this horror reader, who still has the original paperback in pristine condition 17 years later. If you’re in the mood for a big ol' cheap monster movie, where your brain supplies the expensive special effects, you can't do much better than 'Dragon'.

'Relic' is a high-budget literary production. Give credit where credit is due, to Tom Doherty's forward-looking Forge imprint, the sort-of mainstream alternative to Tor books. Nobody would pretend that it is high literature, but Preston and Child took their subject seriously. They wanted to convince you that there could be a South American monster running around a museum, and between the two of them they provide high entertainment and a certain level of seriousness. Preston leveraged his American Museum of Natural History connections effectively, and with Child's help he tweaked a place of wonder into the perfect setting for horror. The monster itself harkens from many of the same inspirations that Schoell used to create 'The Dragon'. In fact, the front cover describes it as: "'Alien' Meets 'Jurassic Park' in New York City." But it goes far beyond that, spinning the monster itself into a sort of crypto-zoological mystery. By that, I mean that part of the joy of this novel is solving the mystery as to what precisely the monster both is and isn't. Preston and Child don’t just tell us that someone shipped a big, slimy thing in a box and set it loose. We don’t know exactly what is in the museum, and it changes as time goes by. Preston and Child subject the monster trope to mystery-genre and even character development, to keep you guessing just how bad it can be, and yes, it can be pretty bad. It certainly helps that the novel is a straightforward, nicely-designed hardcover novel. It looks like a novel that an adult would read, which is a claim that can't really be made for 'The Dragon'. At the end of the day, it's nearly as fun as 'The Dragon', thanks in no small part to a bit character–Special Agent Pendergast–who became the focus of a series of pretty damn successful follow-ups. Both 'The Dragon' and 'Relic' benefit from an adroit combination of the mystery genre and the monster trope, that is, they both keep us guessing what exactly the monster is. Now Schoell brings his beast out early and often, while Preston and Child keep theirs in the shadows longer, but the exact nature of the beast is not made clear in either case until very late in the game. It's an effective tool that makes both novels more enjoyable.

'The Ruins' certainly starts in this vein. Once again, the premise is pretty simple. Four young American tourists, just out of four years of college, on the beach in Mexico, decide on a lark to seek out some Mayan ruins. They’re joined by a German and a Greek, neither of whom speak a lot of English. This proves to be a Bad Idea. Like Preston and Child, Smith brings a nice veneer of quality to his tale. The characters are finely written, with lots of attention to detail. Smith captures the fear of the pampered Americans, separated from our life of ease and constant, monitored safety just for a moment. Just long enough for things to go very wrong. And he very cleverly conceals the nature of what is after them, cloaking it in jungle-dripping atmosphere. This is pulp, in a sense, but high pulp, the kind of literature that gives you nightmares with high production values and great special effects. Like Preston and Child's novel, Smith benefits from a big-press publication and a huge print run. As do Preston and Child, Smith uses the mystery genre and his small-scale predilection to great advantage. It's been a long time since he busted out with 'A Simple Plan', and this novel retains the small scale of that work. There's an almost obsessive focus on the tiny details. And there's a nice continuum here, from the humble but big-screen beginnings in Schoell's 'The Dragon', to the Masterpiece Monster Theater feel of 'Relic', to the stripped down luxuriance of 'The Ruins'. The South American horror novel is here to stay. Let it rot underground for a few years, and it will burst forth again. Just hope that it does not decide to do so via your eye-sockets. |

|

06-27-06: Marianne de Pierres and Parrish Plessis |

||||||

Coming

Down From Orbit

No, no, no, get yer mind out of the gutter. Not that kind of book. I'm talking about a good ol' cheesy cyberpunkette detective novel. The kind you might pass right by if you didn't know better. Well, no excuses in this case, even for me. The second book in Marianne de Pierres' Parrish Plessis series, which began with 'Nylon Angel' is 'Code Noir' (Roc / Penguin Putnam ; July 2006 ; $6.99). I did miss 'Nylon Angel', but 'Code Noir' looked good enough that I went back got the first one. First released by the esteemed Orbit imprint in the UK, these novels may not change your world but they may rock your socks. Sure, the world needs to change, but not as much or as often as your socks. 'Nylon Angel' introduces Parrish Plessis, leather-clad bodyguard in a post-cyberpunk urban hellhole called the Tert. When you're hot like that, you have no choice but to work for a psycho and get yourself framed up for a murder you didn't commit. Throw in a few experimental genetic modifications, 283 pages and an engaging, mordant sense of humor. A decent cyber-noir plot, some bread-board Mickey Spillane. To that add some sunscreen, a spot at the local seaside pavilion and a six pack. You got yourself an afternoon of fun in the sun and anytime your imagination lags with regards to Parrish's assets, well Just Look Around. Problem solved! And you know, the cover is actually less risqué than those Mickey Spillane covers.

And finally, there's 'Crash Deluxe'. No, it's not a video game novelization, though you might want to be aware that there's a Parrish Plessis RPG. (Supply your own leather outfits.) You'll have to either wait a year for 'Crash Deluxe', or go overseas, and get the Orbit original. Either way, it rounds out the story, wraps up the loose ends and leaves everything, if not shipshape, at least no doubt shapely. And while the Parrish Plessis novels are not Books of Big Thinks, they are well-written mysteries with a nice over-layer of black leather, of course and near-future techno-tyranny themes. And for all that those Books of Big Thinks like to make us Think Big, it often turns out that reality maps more closely to the exploits of hot babes in scanty outfits than it does to the weighty predictions of Big Brains with Big Bucks. For all the cool cohorts you'll find the vicinity of Parrish Plessis, they're no match for those you'll find hanging out with the author Marianne de Pierres. Check out her website, which gives you the scoop on ROR, wRiters On the Rise, a group of Aussie originals that includes Margo Lanagan, Cory Daniels, Maxine McArthur, Trent Jamieson, Tansy Rayner Roberts and Richard Hartland. The idea here is that one can presume that these are Names to Keep an Eye Out For. Some of them have novels, some short stories, probably most of them will show up on our shores in paperback shortly, especially as Orbit US gets launched. This is how you find good fiction, by finding authors and then tracing their buddies. Either that, or by picking up the books with girls in black leather on the cover. How can you go wrong? |

|

06-26-06: A 2006 Conversation With James P. Othmer: ; Tad Williams is 'Rite' |

||||||

Talking to 'The (real) Futurist'

I didn't know all that much about Popcorn, beyond the fact that she made annual prognostications that often included trend-setting observations. Popcorn brought us the terms "couch potato", "ergonomics" and "cocooning". So, I looked up her last two years' worth of "this is the future" lists, and then looked up Popcorn herself. On a whim, I decided to see if I could talk to her and find out if she'd read Othmer's satire of her profession. I was curious to see what she thought about it, and wanted to learn a bit about how she did what she did. Popcorn is an industry unto herself, a consultant for Fortune 500 Companies who helps them make strategic marketing decisions. She was pretty much perpetually in meetings. But her assistants were incredibly helpful, and mere minutes before my interview with Othmer was to begin, I managed to get a phone call from Popcorn herself. The first thing she told me was that she and many on her staff had read 'The Futurist' and they all loved it. She thought it was "cute", which is an interesting perspective because the novel is pretty lacerating and relentless. Those in her BrainReserve who read it thought (as I did) that it was very, very funny. I was glad (and perhaps a tad surprised) to hear that she'd read and enjoyed it. Being able to laugh at one's self is a very useful skill.

[*This number was a victim of my bad handwriting, see above.] I'm immersed in the world of science fiction, which is most assuredly not engaged in predicting the future but rather in using it as a metaphor to explore and explode issues in the present. I found this real-world application of imagining the future really interesting, and Popcorn was not the glib TV personality I expected. Yes, the glib TV personality exists, but she's, as Vernor Vinge would say, the pointy end of a very long stick, the single front-end for an immense and complex operation, and at that, just one, public aspect. She's using very old and very reliable communications technology and organizational structures in a pretty innovative fashion, creating a network that she can travel around within and then aim at a particular aspect of our culture to data mine for business opportunities where none might be perceived–in the present. I found this whole world of futurists really fascinating. Science fiction writers could learn a lot from professional futurists, and to my mind, futurists can learn a lot from science fiction writers. You’d think there would be more of a crossover between the two, but for the most part they operate in very separate streams. There are good reasons for this. Science fiction writers are not trying to predict the future and futurists are. The futurists do not want their clients thinking that they're shelling out consultant fees for fiction. They're paying for facts. And science fiction writers are not trying to sell products, other than their fiction, which offers insight and entertainment. So, no crossover, right? Well. Ahem. Like it or not, both groups are studying the very same material. That would be past and present history. And more importantly, both groups are using language to create a product. Sure, the products are very different, with very different intents. The futurists are creating marketing studies, and the science fiction writers are creating myths and stories. These are end products that could not be more different. Where the synergy lies, I believe, is in the use of language to create these end products. Sure, a marketing projection is not an interesting story for anyone other than the client. And a science fiction novel is not going to sell some Fortune 500 company's products. (Unless the product is a Star* franchise novel.) But both groups of creators can quite effectively get outside of their own discipline by dipping into the language, the pure words that each set creates. They can get some much-needed perspective, an outsider's point-of-view. As the necessities of life become ever-easier to manufacture, the process of advertising and marketing those necessities becomes ever more important. It's no wonder that we're seeing a small glut of novels about the marketing process; witness David Louis Edelman's 'Infoquake' and Othmer's 'The Futurist'. They're very different novels, but they both partake heavily of the language of the marketing world, the language of futurists. They benefit from this, just as, I'm sure, the world of professional futurists and marketers would benefit were it to make a concerted effort to understand the cutting and not-so-cutting edge of science fiction. Science fiction may not show us tomorrow, but it sure casts an interesting light on today. Plus, good science fiction is pretty easy to find, if you know where to look. Good futurist writing? Maybe not so easy to find, I think. But between futurists like Faith B. Popcorn and Wally Wacker, we can get a start. It's easy for the artistic world of imaginative writers to sort of dismiss the work of marketing professionals as crass commercialism. That may be the case, but it's abundantly clear that if anything, our future is crassly commercial. Now imagine all this happening in the lobby at KQED. It's a sunny morning in San Francisco, and this flagship NPR/PBS studio is bustling. Two HD flatscreen monitors are displaying closed captioned Sesame Street and an American History doco. James P. Othmer shows up on time, happy and relaxed as one can be having spent some twenty years in the trenches at advertising firms in New York. He was on the, shall we say, manufacturing side of the futurist world. He was also full of both great advertising agency stories and some great literary and cultural insights. It was one of the easiest interviews I've ever done. We just sat down and talked, and in a manner that could only be podcast. Be warned that this is not for the ears of the easily offended. But if you're expecting entertaining edification, well then you've got the opportunity to download either the MP3 or the RealAudio files. All I can say is: Go Army! Yes, it would have been nice to have had Faith B. Popcorn there via a three-dimensional telepresence link. And whether that thought falls into the realm of futurism or science fiction is an exercise left to the readers. |

||||||

(Relatively) Short Work

Tad Williams writes some big-ass books. No, that's not unusual in the SF&F field. Lots of folks write big-ass books. Williams writes fantasy, which when combined with big-ass usually boils down to "pretty darn serious." Oh, there are humorous fantasy writers, but the land of trilogies is not rich with jokes. All that world saving and sword swinging gets to a person. Drenched in the blood of your enemies, laughter is not generally the first response of the ordinary character or writer. I've yet to see a writer drenched in the blood of his or her enemies. I'll allow that, so there's a potential for error in that statement. But until I see that laughing, blood-drenched writer, I'm sticking to my thesis. Heroic fantasy might have touches of humor, to lighten the load, but it is not, in essence, funny. Tad Williams, on the other hand, given the evidence in 'Rite' (Subterranean Press ; December 29, 2006 ; $40) is funny. He's laugh-out-loud funny, he's chuckle-to-yourself funny, he's smirk-in-silence funny. 'Rite' gives him the chance to be funny by virtue of what it is not. What it is not is a big-ass entry in a fantasy or science fiction series. What it is is a collection of Williams' short work. If all those big-ass books have scared you off from Williams' work, then you might want to avoid this one as well. You read a bit, just a bit of this book, and you'll like Williams enough to want to go out and buy those doorstops. You'll like Williams enough to want to read those doorstops. You might even want to invite him over for dinner, like Michael Moorcock did. He probably won't offer to paint your house, unless you're Michael Moorcock, though, so–don’t count on that. On the other hand, this collection of just-about-every-damn-shorter-than-a-doorstop thing that Williams wrote can be counted on as a source for laughter and some decent insights. I've got to really, really like a guy (though not enough to paint his house) who suggests that Philip K. Dick's iconic, near-perfect 'The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch' is a horror novel. That is precisely what I've though about much of Dick's oeuvre, and Williams must be really smart because he agrees with me and identifies the same source of (to both of us) ULTIMATE TERROR. To wit, the possibility that you might lose your damn mind. That bit comes from an introduction he wrote, which should suggest (or warn, depending on how you feel about such items of writing) just how thorough (or desperate) this collection is. Now, I'd be the first to use that parenthetical description were it not for the fact that especially in his little, shorter, toss-em pieces, Williams is not only engaging, he's, wait for it, funny. And just to show how recursive this can get, even his introductions to his introductions can be funny. And, by virtue of their very existence, rather Philip K. Dickian. At 464 pages, I'm not sure that 'Rite' qualifies for the description of "big-ass book". Sure, it might do as doorstop in a pinch, but the end result of reading his work is likely to ensure that it does not end up stopping any doors. I'm leaving it as an exercise to readers to find those big-ass books that will do perfectly well to stop the doors. And they must be stopped. They MUST! Even if we must tell jokes while soaked in the blood of our enemies. In a world where doors go unstopped, freedom itself is at risk. Yes, SF&F can save the world. Take that as a given. |