|

|

11-13-09: The World Goes Weird with Daryl Gregory and Alan Deniro : From 'The Devil's Alphabet' to 'Total Oblivion more or less'

Books offer us nothing less than the world. Every book we pick up is a world unto itself, fashioned not just by the writer, but as well, by those of us who read them. In the moments we read, we make the worlds anew. It's a heady feeling, scary, yet somehow bracing, when worlds imbued with the fantastic seem more relevant than those that aspire to mimic mundane reality.

I speak from the advantage of having received two books that explore our world by spreading a liberal dose of the fantastic around and watching what unfolds. 'Total Oblivion, more or less' (Spectra / Dell / Bantam / Ballantine / Random House ; November 24, 2009 ; $14) by Alan DeNiro and 'The Devil's Alphabet' (Del Rey / Dell / Bantam / Ballantine / Random House ; November 24, 2009 ; $14) by Darryl Gregory both want us to believe that our world is overrun with weirdness. Frankly, that's not so hard to believe.

DeNiro, whose previous book was a collection of short stories, 'Skinny Dipping in the Lake of the Dead,' offers readers a world in which the past has come back not to haunt the present, but to overrun it with horsemen and plagues. Like many worries these days, for community college student Macy and her family, it starts out vague and in the background. But unlike global warming and terrorism, this particular distortion of life as usual arrives here in the US of A on horses, whereupon it rides into the state capitals, closes up the post office and generally re-orders, or rather disorders life as we know it. But though it is no longer the life we knew, we still manage to keep on living, horsemen, plagues and whatever be damned. Or at least as damned as we are. DeNiro writes with an easy sense of the absurd, spinning out really weird scenarios with complete amplob and a very nicely understated sense of humor. Even in a world where we ourselves begin to change in ways we can't quite understand.

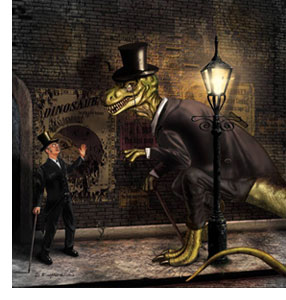

Darryl Gregory wrote last year's 'Pandemonium,' a wonderfully surreal novel with demons and Philip K. Dick haunting a peculiarly re-imagined America. Like his characters, who tend to be young men who return to the scene of the weird, he's back again with 'The Devil's Alphabet' in which a mysterious sickness transforms the inhabitants of the town of Switchback, Tennessee into a variety of monsters. Paxton Abel Martin is one of the few who escaped unscathed, at least, on the outside. Fifteen years later, he returns to murder and mysteries more pressing than death itself. Gregory's work is dense and intense, our life observed through a monstrous filter that somehow makes monsters more relevant the humans we see every day — probably because they're not so different.

Both books offer readers what at first appear to be alternative visions of reality, of the world overrun by the past, chock-a-block with monsters and secrets. And we read these books, immerse ourselves in these worlds with pleasure, only to return to a reality where the present is indeed being overrun by the past, only to return to a world people by monsters who are all-too-human. People like us.

|

|

11-12-09: Books Worth Re-Reading, Ramsey Campbell Edition : 'Cold Print' by Scream/Press

This is an easy one. It practically jumped out of the bookshelf at me. Perhaps I should say slithered. But then, oddly, for me, there is something kind of comforting about reading and re-reading Cthulhu mythos stories. When I sit down with a familiar tale of cosmic dread and urban dislocation, I get a nice warm feeling of familiarity. Unimaginable monsters lurking in the suburban house next door? Sounds like home to me.

Of course, if you're going to re-read Ramsey Campbell, especially his mythos collection 'Cold Print' (Scream/Press ; 1985 ; $15), you must read the Scream/Press edition, illustrated by J. K. Potter. Yes, there's a UK version from Headline that's worth owning, because it has a few stories that aren't in the Scream/Press version. But for re-reading atmosphere, you really need the Scream/Press edition. A quick look on Bookfinder.com shows me that this morning, you could pick up both — the UK Headline version will set you back $20 (it's an ex-library copy) and the Scream/Press starts at around $50 and slowly spirals upward. Let's presume you have your copy to hand. Delight and terror await you.

Campbell is clearly the closest to mainstream literary writing when it comes to Cthulhu mythos tales. His work draws on urban and suburban angst as often as it does the hideaous depths of the cosmos and the eldritch inhabitants thereof. This is not to say that all the stories in 'Cold Print' are calculated works of literary fiction, not at all. But readers who have first encountered Lovecraft via his Library of America volume will feel pretty well-rewarded when reading the stories in this book. There are a few pastiche-ish pieces, but by and large, Campbell carves out his own territory, mining the Lovecraft mythos for imagery and atmosphere to enhance his tales of urban alienation and loneliness.

Reading the stories in order is not a bad idea, as they are almost chronological, allowing you to see Campbell's growth as a writer. The opening tale, "The Church on High Street" has the attractions of more basic Lovecraftian tale — writings from ancient volumes, name-checks for a few Lovecraftian entities, a church that is more than it seems to be and a classic "found manuscript" ending. It might not win any literary awards, but for those of us who have grown up on this stuff, it's just like coming home – fungus and all!

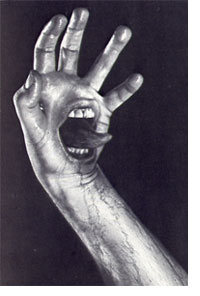

But the stories progress and Campbell slowly begins to tread his own turf, with the title story being particularly significant. Here's the story of a lonely reader, just hoping to pick up some particularly dirty books. Not surprisingly, he finds a bookseller who offers much more than he expects. But Campbell's story evokes the eternal unease of those who seek out pornography, and rewards it with an image that it horrifically pornographic. Moreover, it’s an image rendered into disturbing life by J. K. Potter, and one that has been eternally ripped off since this, the first publication.

But the stories progress and Campbell slowly begins to tread his own turf, with the title story being particularly significant. Here's the story of a lonely reader, just hoping to pick up some particularly dirty books. Not surprisingly, he finds a bookseller who offers much more than he expects. But Campbell's story evokes the eternal unease of those who seek out pornography, and rewards it with an image that it horrifically pornographic. Moreover, it’s an image rendered into disturbing life by J. K. Potter, and one that has been eternally ripped off since this, the first publication.

From there on, the stories become both increasingly sophisticated and disturbing. Campbell, who aims to be a master of mining unease, goes after drug use and hints at sexual confusion. And he imbues all these stories with imagery that is surreal and disturbing, the perfect realization, in many ways, of the Lovecraft ethos of showing us just a part of the monsters. And yes, here be monsters.

I've reproduced that classic Potter print from the title story, but there are a number of others. To my mind, the black and white treatment is perfect. It lends the works a sense of the dirty, the forbidden, the things you wish you could unsee. When you've finished with the Scream/Press version, you can back track to the Headline volume and pick up the stories you missed. Lodge them in your brain for a few more years and let the world wash them away. Perhaps.

|

|

11-11-09: World Fantasy Convention Interview with Michael Swanwick

This is the first of a series of email interviews done for the World Fantasy Convention Booklet.

Michael, you have a great story about your beginnings as a writer. Could you tell us that story, and the importance of that story to your work as a writer?

I came to Philadelphia in the winter of 1973 with seventy dollars, a two-pack-a-day cigarette habit, no marketable job skills, a friend who’d offered to put me up for a few weeks on his couch, and the absurd and unshakable conviction that science fiction was the highest form of literature and that I could teach myself to write it.

Over the course of that long and bleak winter, I sold my blood, typed term papers for a dollar a page and ghost-wrote them for not much more, held down the kind of temp jobs where you have to physically harass your employer to get paid, and lost forty pounds from not having enough to eat. I vividly remember early one Sunday morning seeing a sack of Italian bread left at the door of a restaurant that wasn’t open yet and walking around and around the block, arguing with myself whether I was close enough to starvation to morally justify stealing a loaf.

I lived off the charity of art students, staying in rooms briefly left vacant between housemates, and in living rooms where I rolled up newspapers and stuck them between the windows to cut down on the cold winds blowing through the house. All the while I was trying to write, inventing words and imaginary grammars, imitating William Burroughs and Vladimir Nabokov and Gene Wolfe and Thomas Pynchon and Ursula K. Le Guin. Badly, of course. I hadn’t figured out how to actually end a story. I could only write fragments.

Come spring, I got a job as a Clerk Typist I for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. I took over a student’s lease on a room across the street from Sister Minnie’s Kitchen, which was no longer a restaurant but a flophouse, and next door to the Sahara Hotel, where the only furniture was a bed, the beds had no blankets, and the rooms rented by the hour. In the dark hours of the morning, I would sit in the window recording the screaming arguments between the whores and their pimps on the street below (contrary to what we’re told, the pimps never won!) and transcribing my nightmares. I went to open poetry readings and read lists of spaceships in orbital vacuum-docks, and mapped out elaborate worlds that were fusions of Delany and Ellison and Garcia Marquez. I wrote many, many story fragments, a few of which I still hope to complete someday.

Come spring, I got a job as a Clerk Typist I for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. I took over a student’s lease on a room across the street from Sister Minnie’s Kitchen, which was no longer a restaurant but a flophouse, and next door to the Sahara Hotel, where the only furniture was a bed, the beds had no blankets, and the rooms rented by the hour. In the dark hours of the morning, I would sit in the window recording the screaming arguments between the whores and their pimps on the street below (contrary to what we’re told, the pimps never won!) and transcribing my nightmares. I went to open poetry readings and read lists of spaceships in orbital vacuum-docks, and mapped out elaborate worlds that were fusions of Delany and Ellison and Garcia Marquez. I wrote many, many story fragments, a few of which I still hope to complete someday.

Six years later I finally finished and sold my first story. I was twenty-nine years old, engaged to be married, and I’d just lost my job.

I look back on that young man today and realize that he was absolutely mad. There was no objective evidence that I had any talent whatsoever. But I was stubborn, and it was my good fortune that I was also right: As it turned out, and to my immense relief, I could teach myself to write fantasy and science fiction.

But it was a close thing for a few years there.

You began writing science fiction in the 1970's, with the New Wave, and were in the vicinity of the cyberpunks as well; since then we've seen others come and go. How do these groups of writers and their manifestos, speeches, anthologies, magazines, conventions and works inform you as a writer?

The apparatus of literary movements can be a terrible distraction for a young writer and a great temptation to sink time and energy into irrelevancies at a moment when all your best effort should go into writing fiction.

What is valuable is the presence of other writers of your same generation who are doing the same sort of thing you are, and writing the kind of stories that you aspire to write. When “Hardfought” by Greg Bear or “Hive” by Bruce Sterling or “My Brother's Keeper” by Pat Cadigan, or “Black Air” by Kim Stanley Robinson first appeared, they all sent me straight to the typewriter to prove that I could do that too. Not the specifics of the story, of course, but something that cool, that sharp, that innovative, that literary. Thy pushed me into new areas. They showed by example exactly how good you have to be to avoid being an also-ran.

When I collaborated on “Dogfight” with William Gibson, we were both unknowns. I told him I liked the image he’d mentioned to a friend of rednecks fighting with miniature WWI airplanes over a pool table and, being a shrewd guy, Bill saw immediately that I had a story in mind. He generously offered to let me have the idea, or else to collaborate with me, whichever I chose. I went with the collaboration because everyone in our cohort was excited about his writing, and I wanted to see up close what kind of chops he had. Gibson is particularly good down on the sentence-and-paragraph level, and the lessons I learned working that closely with him were worth any number of anthologies and manifestoes.

When I collaborated on “Dogfight” with William Gibson, we were both unknowns. I told him I liked the image he’d mentioned to a friend of rednecks fighting with miniature WWI airplanes over a pool table and, being a shrewd guy, Bill saw immediately that I had a story in mind. He generously offered to let me have the idea, or else to collaborate with me, whichever I chose. I went with the collaboration because everyone in our cohort was excited about his writing, and I wanted to see up close what kind of chops he had. Gibson is particularly good down on the sentence-and-paragraph level, and the lessons I learned working that closely with him were worth any number of anthologies and manifestoes.

You started writing shortly after the crest of the "New Wave," which tended to blur the boundaries between science fiction, fantasy, horror and literary fiction. You've written hard science fiction and hard fantasy with urban settings. What do you see as the core concepts at the heart of science fiction, fantasy and horror? Do you see a hard differentiation or a gradation from one to the other?

That’s a book’s worth of question. To simplify, I’ll start by setting aside horror, which I only rarely write and is not a genre at all but an intention or an effect. (As evidenced by the fact that it can be science fiction or fantasy or mainstream, depending on its trappings.)

Immediately before I wrote The Iron Dragon’s Daughter, which is a science-fiction-flavored fantasy, I wrote Stations of the Tide, which is fantasy-flavored science fiction. So I spent several years having no choice but to think about the distinction between the two genres.

The essential difference, it seemed to me, was that science fiction occurs in a knowable universe. Human beings may or may not be smart enough to figure out the rules, but a strong enough intelligence could. But the fantasy universe is ultimately unknowable. At its heart lies mystery. And this mystery is essentially religious in nature. That’s one of the charms of fantasy, the ability to play with spiritual ideas without the moral pitfalls of doing so in the real world. It is also, incidentally, why fantasy worlds that start from a set of rules for magic will so often feel a lot like science fiction. What makes magic fantastic is that it punches a hole in our perception of what is and is not possible, that it takes us beyond the realm of mere rules.

I’m fortunate in that the sorts of stories I want to write fall naturally within the heart of one genre or another, which is for marketing purposes a very good thing. Still, my allegiance is not to genre but to the story itself. When I wrote Jack Faust, I was extremely curious to see whether it would be marketed as SF or fantasy. In the UK it was marketed as horror, and in the US as literary fiction. Which I think pretty much says it all.

What is it that brings you to write a story — in any genre?

The desire to read it. That’s what makes writers so touchy — the fact that what we’re writing, what we’re willing to invest the enormous amounts of energy that it takes to write anything, is the sort of work that we value more than anything else. Only an egomaniac could reconcile having the godlike power to create something like that with being the ordinary human creatures we are — and we’re not egomaniacs. Or, rather, very few of us are.

So there’s your explanation for a lot of our odd behavior.

Could you tell us a little about your writing process ” from first draft to final revision — in both long and short forms?

It’s the same for both forms. I come up with an idea and I play with it until I know how it’s going to start, have some sense of what it’s going to look like, and (if I humanly can, but this isn’t always possible) how it’s going to end. This process can take minutes or it can take years. I may take notes. When the story’s ready, I begin to write. Knowing the ending means that I can drive the entire plot toward it, making it feel inevitable when it arrives, while deliberately misdirecting the reader’s expectations, so that it also comes as a surprise.

Once I’ve started typing, I write for as long as the prose feels solid beneath my feet and capable of supporting everything that is to come. This can be anywhere from a couple of paragraphs to four pages. Then I go back to the beginning and start over again. When the first page or so has been written without any changes two or three times, I start the rewriting from page two. At the end of the day, I’ll print out a copy of the active part of the novel and sometime in the evening, I’ll look over it and mark it up, in order to get a jump start on the next day.

This process makes it meaningless to talk about the number of drafts the novel goes through. Each page has been revised and rewritten several and often dozens of time. But when I reach the final page, that’s it. I don’t go back to the beginning and start over, because the novel is finished. This is a terribly inefficient, work-intensive method, which I don’t recommend to anybody. Unless, like me, it’s the only one that works for you.

Sometimes, when I’m stuck for what comes next, I draw plot diagrams. But that’s a whole different topic.

Could you tell us about your writing day?

It’s pretty dull. I have breakfast, I go upstairs to my office and I write. That’s it.

What are the most important things outside of writing that contribute to your writing?

God, everything. Travel, science, the random experiences of life that clutch at your heart. When I was young, I was traveling with a group of friends toward an event or destination I have long forgotten and the driver stopped at an elderly relative’s house. Her walls were thronged with framed photographs of relatives. She sat my friend down and, pulling out a photograph album from a stack under the coffee table, said, “This is your Great-Aunt Margaret’s daughter Barbara. She married an insurance salesman named Martin Greenfeld, and they live in Tucson with their son Rob.” And so on, through five or six photos from as many albums. Afterwards, it struck me that this woman was holding together an enormous extended family with her knowledge, and that when she died, a great many people would no longer be related to one another in any meaningful sense.

This is one of countless moments good enough to support a story or a chapter or a scene which I’m hoarding in the hope that someday I’ll find the right employment for it it.

Since you started writing, we've seen all of the tropes of science fiction and fantasy become parts of mainstream culture — and yet there is still a very strong sense of what is genre and what is not.

Only because we haven’t challenged the definitions and boundaries sufficiently. A book like Vladimir’s Nabokov’s Ada, in which history flows backwards and there are distorted glimpses of an alternative world which is clearly our own, is inescapably science fiction. Virginia Woolf’s Orlando is, if not sf, at least fantasy. Such works are discriminated against, by us, simply because they’re so beautifully written.

On the flip side, there’s the very common experience of being told that one is not “really” a genre writer because one’s work has literary merit. I’ve urged Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun on countless non-genre readers, who have all loved it. But he won’t get the front-page reviews he deserves in the New York Times Book Review, merely because he stands on the wrong side of the genre divide.

I believe not in boundaries but in centers. In the Ural Mountains, in Russia, I stood with one foot in Europe and the other in Asia, and the meaningful distinctions between the two were nonexistent. Still, you can say that Beijing is in the heart of Asia, that Paris is extremely European, and that Moscow is about as Russian as you can get. Similarly, a novel with elf-lords riding dragons is identifiably fantasy, one with engineers terraforming an ice-world is clearly SF, and one exploring the disintegration of a marriage in contemporary Duluth is obviously mainstream. Largely because they were written as such, in imitation of a large body of similar works. But there’s a lot of innovative work that’s written in total disregard of where it’s going to be shelved. The adventurous reader will seek them out.

Fantasy, by definition, includes elements of the fantastic that cordon it off, so to speak, from realistic literary fiction. When you include these elements in your fiction, or use them as a premise for creating an entire world, how do you see the resulting work interacting with or reflecting our everyday world?

The fantastic makes it possible to say things that cannot be said naturalistically. I once wrote a story in which consciousness flowed backward, so that you knew everything that would happen until the instant you died — but not who the person you just woke up beside might be. Your spouse? A one-night stand? Now, in a mimetic story, the only possible reading is that the protagonist is mad. Which is not very interesting. But in “Foresight,” I was able to explore the question of whether it’s possible to have free will in a predetermined universe, and without resorting to allegory or ponderous philosophical exposition.

I simply wound up the tale and showed what happened.

It is a very different thing to write “Picasso was a wizard” in a fantasy story than it is in a mainstream one. It extends human thought beyond its normal limits.

Has the spectacular success of young adult fantasy serial fiction had an impact on your fiction in particular?

Could you talk about how it is changed the genre itself?

It hasn’t changed my work, and I don’t think it’s changed the genre in any important sense. I have nothing bad to say about the Harry Potter books, but they were written by a single mom trying to make enough money to get off welfare. You don't strive for innovation under those circumstances; you strive to entertain. And of course those writers inspired specifically by her example are more interested in success than in revising the forms of fantasy. (I have nothing bad to say about them either, I hasten to add. Keeping off the dole is an admirable enterprise.)

Probably the biggest influence those books will have is via the readers they've brought into fantasy, or rather that fraction of those readers who become writers. Those who hadn’t encountered wizards, monsters, and fabulous beasts before, and to whom such things came as a revelation. This is how a genre mutates, via writers who see more possibilities in a work than did its author.

Come to think of it, the first of them ought to be entering the field right about now.

Young adult fiction is increasingly read by adults as well as the intended, or at least, included audience of adolescents. Science fiction and fantasy have often been characterized as adolescent fiction; is this of use to you as a writer? Do you find such a characterization helpful, hurtful, or irrelevant —and why?

Adolescents can be the very best of readers because they don’t have the expectations that can come from long familiarity with a genre, and so they’re not upset if at the end of a fantasy novel the heroine becomes a chemist, or if the restoration of the king is a terrible thing, to be averted at all costs. But also because they’re reading in part to make sense of this enormously complicated and confusing world that they’re about to take possession of. So you can write about the nature of sex and maturity and moral responsibility with the expectation that at least some of the readers will think seriously about such issues, and take what you have to say under advisement.

At the same time, there are aspects of any serious work that can only be appreciated with experience. The Lord of the Rings is not the same book at age sixteen as it is at forty. On my first reading, it was the greatest adventure in the world. On my last, it was the saddest book I’d ever read. Everybody in it is in the process of losing everything they hold dear, and their task is to acknowledge the necessity of doing so, to make the sacrifice for the sake of those to come, and then to die. An adolescent simply couldn’t feel that the way an older man or woman might.

I strive to write books so that they can be appreciated by both audiences. But in this I’m not terribly unusual, I suspect.

You created a very complex and enjoyable world in The Iron Dragon's Daughter and have returned to it in The Dragons of Babel. Talk about creating that world the first time around, and what drew you back.

I’ve told this story many times before, but what the heck. I was driving to Pittsburgh with my wife, Marianne Porter, and we were talking about fantasy and then about steam locomotives and I made a crack about the Baldwin Steam Dragon Works. Marianne laughed, we drove on, and a mile or so down the road, I said, “Write that down.” A Dickensian setting like that cried out for a child laborer, so I gave it Jane, a girl who’d been stolen by the elves and put to work building dragons.

What made the idea exciting to me was that it made it possible to write serious fantasy out of my own experience, rather than from the second-hand experience of reading Tolkien, Eddison, or Peake. I could have junkyards, and high school shop classes, and suburban shopping malls. I could have everything! I could make the world as large and varied as our own.

Fantasy being essentially nostalgic, both novels begin in my childhood. My father was an electrical engineer for General Electric and I grew up with a certain familiarity with industrial sites, large machinery, fighter planes, machine shops and the like. So the Baldwynne Steam Dragon Works in The Iron Dragon’s Daughter, while based physically on Baldwin Locomotive’s Eddystone plant, was rooted in experience. The village that Will is exiled from in The Dragons of Babel and the world he journeys into reflect the more idyllic aspects of my youth. Not only all the time I spent in the fields and forests of Vermont (I was an outdoorsy kid), but also frequent visits to family in New York City. NYC maps directly onto Babel, not only physically but psychically as well. It’s a place that millions consider inherently wicked and sinful, but it’s also very comfortable, a congeries of villages and communities, a home to writers and artists, a romantic and magical place, the city my immigrant ancestors made their home, and one I’ve always loved.

I wasn’t going to return to industrialized Faerie, because I had no interest whatsoever in sequels or series. The second book began when I came up with the image of Will running up a hillside to watch the dragons flying overhead. As it caught my imagination, I saw that his problem was the inverse of Jane’s. She didn’t belong in that world, and so she couldn’t find a place for herself in it. He did, and so his job was to find that place. Her quest was religious and his secular. Which meant that the second book wouldn’t be just an extension of the first. I wasn’t even sure at first that both books were set in the same world, which is why there were no commonalities of place names or gods or individuals. Until finally I decided that it did no harm to share the world and would give some of the readers of the first book pleasure. Then I had Jane make a cameo appearance in Will’s book. She’s the only character to appear in both.

The greatest pleasure of writing these books was that I was able to go out and research them in person. I spent a great deal of time wandering through old industrial sites and clambering over steam locomotives. It was tremendous fun.

Could you look back over your career and tell us how you feel about your body of work as whole?

It’s a good start.

The publishing industry is meeting the same challenges the music industry and musicians met some fifteen years ago. What do you think writers and publishers can do to ensure that readership keeps growing and the industry remains a viable source of income for writers? What do you do?

I have no idea what publishers should do. I wish I did, because I have friends in publishing and it would make them happy if I could save the industry.

As a writer, I consciously try to make what I write exciting for the reader — to give him or her more than just a really well-written change on something they’ve read before. I try to give each story something that the reader has never encountered before. Something as big and obvious and wonderful as a giant striding the downs with dinosaurs and tribes of stone-age elves living in the forests atop his head is worth any number of polished and lapidarian phrases.

And of course as a reader, I actively promote whatever seems good to me. When my son Sean was in high school, every Christmas I gave subscriptions to science fiction magazines to his English teachers. Using the school’s address, of course. I figured that if they didn’t read ‘em themselves, they’d at least leave them lying around where they could corrupt young minds. I think everybody should consider doing that.

And finally, tell us about how this year's World Fantasy Convention slots into your work as a writer, and how this convention fits into the larger frame of genre fiction, and indeed, just what is publishable.

It all comes down to the reader. One person, one book, one shared dream at a time. The World Fantasy Convention is a device — a kind of a Rube Goldberg device, admittedly — for conveying a sense of excitement for a particular kind of writing, a way of saying, “Look here! Try this stuff! It’s terrific! Would we be giving it an award if it weren’t? Would we have be having panels about less-than-extraordinary fiction? Would we be having this convention if this stuff weren’t special?”

No, we wouldn’t. And so, here we are.

|

|

11-10-09: Beyond 'The Box' With Richard Matheson : Ticking Time Bombs of Fiction

Go ahead. Buy the ultimately cheesy Matheson movie tie-in. I trust you have the Dream/Press collection of Matheson's complete short stories to really read, to hand on to those whose minds you will infect with the mass-market paperback. You actually need the paperback to do the job right. Here's how this works — or at least how it worked for me.

My mother, or my father, I'm not sure which —I'm guessing it was my mom, because my dad could not abide science fiction — had bought a cheesy paperback some 45 years ago. It was titled 'The Shores of Space,' by Richard Matheson. I remember the day clearly. We had some bookshelves embedded in the wall, where my parents put books that were generally not meant for my eyes. I sat down behind the couch, and started pulling books from the shelves, until I came to 'The Shores of Space.' It was a collection of short stories, and I flipped to the one titled "Blood Son," because, like most sons, I had a sort of rocky relationship with my father.

In the short story, boy ignores his father's advice, and starts spending too much time at the sad local zoo. We had a sad local zoo that my parents would take us too, out at Coyote Point. It always gave me the shivers. "Blood Son" decides to befriend that vampire bat, to let it drink his blood ... until he dies, and his final vision is of his father, fading in the darkness. I was huddled behind the couch, reading the forbidden genre. I don’t think I was ever the same person afterwards.

|

|

11-09-09: A Review of 'Homer & Langley' by E. L. Doctorow : The Eloquent Vision of the Blind

I've already written a bit about 'Homer & Langley' by E. L. Doctorow and the eloquent vision of the blind narrator, Homer Collyer. It's a compact, powerful novel of American history paraded through the living rooms of our most famous hoarding recluses. There's a song in this voice, a keening call for a past wherein our country becomes a foreign country.

'Homer & Langley' (Random House ; September 1, 2009 ; $26) is in many ways a very simple novel. Homer and Langley Collyer spend the years of their lives and most of the American twentieth century watching as America strolls through their apartment on Fifth Avenue in New York. There's a dreamlike aspect to E. L. Doctorow's prose. This is a novel of interiors, the vision a man shut-in from life and shut off from vision. It reads almost like the delicate fantasy of any man who has led an anonymous life, the gentle, precise daydreams of one who was never marked for greatness, only for — continuation. When you read this book, be careful. Understand that you will finish the book with joy, but that the book will not necessarily be finished with you. You'll see your own slow-fade out, and be locked in the blindness of your own life. Doctorow's careful, precise language will rise in your mind. Here's a link to my review.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|